By Van Smith

Published in City Paper, Jan. 3, 2007

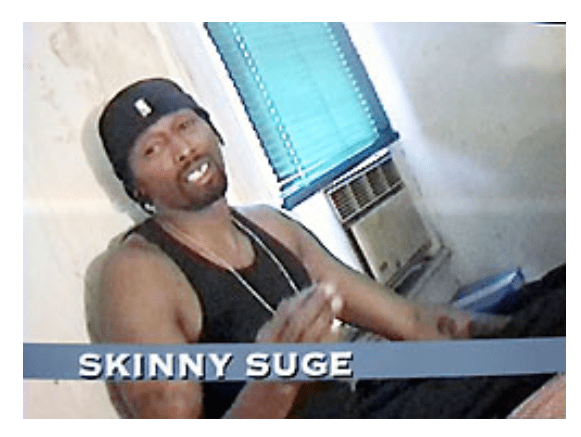

Daniel Gerard Joaquin McIntosh Sr. manages the Talking Head Club downtown on Davis Street, where he’s better known as “Talking Dan.” In the run-up to the club’s announced Dec. 31 closing, though, McIntosh and the club’s president and liquor license holder, Roman Kuebler, kept mum, declining to talk with City Paper music editor Jess Harvell. Working on a story about the closing, Harvell consulted City Paper‘s news side, searching for ways to hunt up the current owner of the building where the business is located. Ten minutes of internet searching later, and it began to look like Talking Dan–who has a lengthy record of criminal charges, including a 2005 pot conviction–might be part of the Talking Head’s problem. Once McIntosh was informed of the findings on Dec. 28, he addressed such concerns at length over the phone.

“I sold some pot, I got into trouble for it,” McIntosh, 31, says of his criminal record. “Apparently now everything I’ve done in my past is going to be an issue with the Talking Head.”

McIntosh says that Kuebler was aware of McIntosh’s troubled past with the law before bringing him in as a partner in the business a few years ago, and that Kuebler was understanding when McIntosh was convicted in 2005 in Baltimore County of possession with intent to distribute marijuana.

“He said, `I know you’re a good person,'” McIntosh recalls Kuebler saying, “`I’m your friend, and I’m not going to hold this against you.'” Kuebler did not return phone calls for this article.

McIntosh asserts that his legal entanglements have nothing to do with the Talking Head closing, which instead is due to a recent financial coup de grace. “We were beating a horse for four years, to make it move,” McIntosh says of the club’s struggling operations, “and then stuff like that happens.” The “stuff,” McIntosh explains, revolves around preparations he and others had made recently to purchase the Talking Head building at 203 Davis St. Their efforts, which McIntosh says included paying for a $2,600 appraisal, came to naught when the club’s vending machine provider, Michael J. DePasquale, Jr., got a contract to buy the place from under the Talking Head. Compounding this wrinkle, McIntosh adds, was the club’s ongoing inability to make timely rent payments and the status of its lease under changing property owners.

What McIntosh didn’t know was that DePasquale filed criminal harassment and telephone misuse charges against him on Nov. 12, 2006, and that a trial date in the case is scheduled for Jan. 4. “I had no idea about that,” McIntosh responds when told. “Wow. That’s very interesting. I’m on probation for my other shit. My next call will be to my attorney.”

DePasquale’s complaint states that McIntosh was “threatening me and my wife” because “he objects to me purchasing a property, that we are settling on 11-17-06–he is a tenant there.” The complaint says DePasquale has saved recordings of threatening messages from McIntosh. “I have told him to stop,” the complaint ends, but McIntosh “continues to threaten our lives and violence [sic].”

DePasquale, reached by phone on Dec. 28, declined to comment, saying the criminal complaint against McIntosh speaks for itself. As for McIntosh’s claim that DePasquale sought to snatch the property up from under the Talking Head, DePasquale says, “you’re a reporter, you know not to believe that.” McIntosh says that DePasquale’s contract to buy the building has since lapsed.

McIntosh, meanwhile, says he would prefer the Talking Head go out gracefully, with prospects for re-opening elsewhere. “I wanted to end it on a happy note,” he says. “I tell you, I just like rocking and rolling, and I’m trying to end it on a nice, exciting note. We’ve discussed a few locations–in a neighborhood of some kind, maybe Hampden.

“I grew up in Hampden, and I’d be into bringing something back, to go back and offer something of pure substance,” McIntosh continues. “I know the names of a lot of those junkies on those corners in Hampden, ’cause I’m a very rare case, one of the few who I came up with who did not wind up junkies or in jail.”

Actually, McIntosh acknowledges, he’s been both a junkie and in jail. In the late 1990s, he did time in York, Pa., on drug charges, and earlier in the 1990s “I was a straight-up fucking junkie–but I don’t see what that has to do with the Talking Head,” McIntosh says. Since then, his troubles have continued, though he says his “intent is pure” and that his more recent legal imbroglios amount to “a few questionable things in the eyes of some,” as opposed to his earlier misdeeds, which were “questionable things in the eyes of everyone.”

The 2005 Baltimore County pot conviction, McIntosh says, wasn’t as big a deal as it appeared. “They had a tip that I was some kind of drug kingpin and came in looking for 100 pounds of weed,” he recalls of the Nov. 3, 2004, raid on his Pikesville home. “And they walked away with an ounce and a half.”

According to the court file, the raid also turned up lights for growing pot and $4,800 in cash. On the same day, police followed McIntosh to another location in Baltimore City, where they recovered 36 live pot plants, six pounds of pot, $41,742 in cash, and two guns.

“They followed me to his house and busted his house,” McIntosh recalls, adding that “it was kind of my fault” the location was raided.

McIntosh was not convicted in connection with the Baltimore City haul, only with what was at his Pikesville home, and he pleaded guilty. The court noted his prior convictions–a 1993 assault and a 1997 drug possession with intent to distribute–and gave him a three-year suspended sentence, 80 hours of community service, and two years of supervised probation.

Just before midnight on Nov. 15, 2004–the day before he was indicted in Baltimore County as a result of the raid–McIntosh was pulled over on Calvert Street in Mount Vernon for having a headlight out. He was found to have a suspended license for outstanding child-support commitments; the arresting officer searched McIntosh and found six Valium pills in his pocket. For that, on Feb. 14, 2005–two days before his Baltimore County pot conviction–McIntosh earned a drug-possession conviction with a 90-day suspended sentence and one year of probation.

Since 2002, when the Talking Head first opened, McIntosh has been embroiled in a series of legal battles with the mothers of two of his three children. McIntosh’s need for legal representation on these matters (not to mention the criminal cases), on top of the responsibilities of being a father providing for his children, translate into a need for income that the Talking Head hasn’t met recently, he says.

The club, McIntosh says, “doesn’t pay anybody anymore, and hasn’t been for six months, and I essentially stopped working there.” Instead, he says he “does a lot of construction work,” and collects rent on properties that he’s involved in. “I come from poor,” he stresses, “so I just roll around and get it where I can–it’s all just money in my pocket.” Things are looking up, financially, he says, since he moved recently to Sparks in Baltimore County.

Since McIntosh’s problems overlap with the Talking Head’s problems–at least insofar as the pending charges filed by DePasquale are concerned–McIntosh seeks to distance himself from the club. “I’m not actually the owner of the company,” McIntosh asserts. But the 2005 renewal application for the club’s liquor license, which was filled out by Kuebler, the licensee, lists McIntosh as 25 percent owner, with the rest belonging to Kuebler. “That’s roughly true,” McIntosh says, “but that’s just something that Roman said–there’s nothing in the company’s corporate charter about that.” Kuebler did not respond to requests to clear up the questions about the club’s ownership structure.

McIntosh, meanwhile, decries City Paper‘s interest in his problems. “This is not something the alternative press should be doing,” he says, adding that “you’re going after the wrong side here.” His complaints about City Paper aren’t new. In the 2005 Best of Baltimore issue, the club was designated “Best Rock Club,” and, while praising its esoteric bookings of local and traveling bands, the write-up included an unsupported observation about Talking Head Club’s “laissez-faire approach to underage drinking.” The paper apologized in print for the misstep, but McIntosh was agitated by the insinuation.

In talking about his problems and the end of the Talking Head for this article, though, McIntosh speaks at length, in reasoned tones, with an it-is-what-it-is attitude.

“I just felt the need to call you and say a few things because it would be a shame for all who are involved with the club to be tarnished by me,” he says. “I’ve looked at my [court] record before, and said, `That guy’s a fucking killer,’ so I can understand” why it’s newsworthy. “But, as crazy as [the record] looks, every single one of those things is easily explained. It’s all been blown out of proportion.”

Talking Trash

Published in City Paper’s “The Mail,” Jan. 10, 2007

I couldn’t believe my eyes. Baltimore loses one of its only small venues promoting indie/avant music and you eulogize the loss with a smear piece (“Talking Head,” Mobtown Beat, Jan. 3). Dan McIntosh’s criminal record has absolutely nothing to do with his management of the Talking Head. If anybody at City Paper really got to know the guy, they would realize his heart is in the right place. As 2007 dawns the future looks grim–no Talking Head and an alternative weekly that has descended journalistically to the level of a shitrag.

Matthew Selander

Baltimore

“Travesty” sums up Van Smith’s recent pulp schlock, ostensibly on the long-anticipated closure of the Talking Head Club, but more so a hatchet job of sensationalist journalism. I’d imagine it would be more than a little embarrassing for CP‘s senior editors to concoct apologia for Smith’s giddy voyeurism masquerading as investigative reporting.

The irony, however, is at our voyeur’s expense. His breathless expose of the seedy inner workings of this fringe club confuses a “scoop” with public knowledge. Didn’t he find it a little striking how unabashedly candid Dan McIntosh would be with a reporter, and on the record? Besides, anyone with even a pedestrian familiarity with the goings-on of the Davis Street building over the past decade-plus, including years long before McIntosh ever made his mark, might find the prudish swoon of the piece a little sigh-inducing. “Vice in a dive bar!? Well, I NEVER…!”

With questions about a third incarnation of the Head remaining just that, I think we can do without the boring kind of rock-scene hagiography we’d often get at a time like this. However, I can’t help but lament a wasted opportunity to give voice to the thoughts of the many Davis Street faithful that damn near grew up in that weird Tudor hovel, or at least give a decent account of its time as the Talking Head with some sense of context and history for the younger crowd.

But then again, maybe it’s kudos for Smith over on Park Avenue; his muckrake has caught whiff of just the kind of juicy poot that CP intends for the Annals of Baltimore Scene Legend! Or maybe they could just dig a little deeper into that DePasquale guy for some truly buff stuff….

Michael Baier

Baltimore

So City Paper did a bit on Dan from the Talking Head in regard to its closing. Whereas an article on the history of the building, who’s been in there–Talking Head, Ottobar, pre my time, etc.–and all the great stuff the place has done would have been rad, instead City Paper decided to smear Dan across the page.

I pretty much think that is horseshit.

Are you going to tell me everyone has a clean past with no screwups? Hell…I was arrested at the age of 14 for possession and attempt to distribute with marijuana and speed and subsequently expelled from high school for a year. I have had many an unpleasantly ending relationship that you could dig some dirt up on, I’ve stolen, got in fights, did my share of property destruction here and there, played the I-don’t-care-about-anyone-but-myself gig…but you know, that is what got me to here, where I am today: operating the Baltimore Free Store and really being able to make an impact on Baltimore.

Running Dan into the ground was a low blow and really put a bad taste in my mouth with regard to City Paper. We all have skeletons in our closet. I don’t see why it is necessary to display them to the world, especially when it seems like all it is is a back and fourth between City Paper staff and one individual. I don’t see how his past has anything to do with the Talking Head. If you were trying to pass judgment on his managing abilities as reasoning for the closing of the Talking Head, then you need to bring up issues that relate to business practices, not drug use or issues within his personal life.

I love you, City Paper, but sometimes you make me want to use you for kindling rather than reading.

Matt Warfield

Baltimore

Your story about the closing of the Talking Head nightclub sounded more like an episode of America’s Almost Wanted than it did a story about a group of Baltimore artists, entertainers, restaurateurs, and impresarios who came together earlier in this millennium to successfully establish and run an extraordinary music, social, and beverage venue by, of, and for the people of Baltimore.

And despite your insinuations to the contrary and your largely irrelevant information about the club, the folks who kept the Talking Head going these years (including the “president and liquor license holder” Roman “Guitar” Kuebler) in my view have consistently behaved conscientiously and even scrupulously with regard to their legal and dare-I-say social responsibilities and obligations under the law; this continuing attitude on your part to suggest otherwise borders on libel, and if not that, at least dickheadism of the worst kind.

I for one would rather know how the joint came to be, who played there, who went there, and where they will go now in Baltimore for a true alternative venue.

Frankly, the building on Davis Street, in my opinion, is a not-quaint, disgusting firetrap with dysfunctional plumbing, poor acoustics, and not nearly enough “liebensraum” for the rockers and rollers and movers and groovers who happily congregated there and supported the noteworthy tunesmanship of the Talking Headers.

Its new owner would do well to erect a nice little parking structure or another “badly needed” law office building. Seriously.

Hopefully, the TH folks will find new permanent quarters and continue bringing the Baltimore experience to music lovers from around the globe and beyond.

And why don’t you investigative journalists down at City Paper cut the Chris Hansen-esque bullshit and do something productive with your talents like reviewing my album.

Walter T. Kuebler

Lutherville

The writer is Talking Head co-owner Roman Kuebler’s father.

I was shocked and appalled at the article this week about the end of the Talking Head. I can only hope anyone who knows anything about that place, its owners, and their ongoing feud with your paper sees right through the thinly veiled final stab you took at Dan McIntosh now that you don’t need to coax him for his advertising. However, that actually isn’t why I was so angered. What has angered me is you chose to print a pointless story, when the real story there was about the building itself, and its place in Baltimore music history. I came across that history in the late ’80s, performing some of my first gigs in a band at the club called Chambers, and from that point on in my life, that building became synonymous with good underground music and a place where Baltimore’s underground could come and be their freaky selves. From those days of Chambers, to the birthplace of the Ottobar, to its last incarnation as the Talking Head, 203 Davis St. has been an integral part of the music scene in this town for over a quarter of a century. What occurred on New Year’s Eve, when the Head shut its doors for good, was not the death of one club, it was the death of an era. Instead of eulogizing it properly, you spit on the grave, and for that you should be ashamed.

Lonnie Fisher

Baltimore

The writer is the proprietor of Sonar, where Dan McIntosh now works as a manager.

Editor Lee Gardner responds: For the record, there is no ongoing feud with the Talking Head, at least on City Paper‘s part. I’ve known co-owner Roman Kuebler for at least a decade; I like him and respect him. My only encounter with Dan McIntosh was essentially an extended argument, but he impressed me as a passionate guy. In the wake of dust-up regarding the 2005 Best of Baltimore issue–an incident, speaking personally, that I regret–City Paper employees continued to frequent the club and we continued to write about its shows. We were a media sponsor of its Reverent Fog Festival last September and awarded it Best Rock Club again in the Best of Baltimore issue that same month.

As explained in Van’s story, we fully intended to do a fairly standard farewell-to-the-Talking Head story in our No Cover space. Noncooperation from the club’s principals led to some cursory internet research to try to confirm some basic facts, which lead us to information about McIntosh’s criminal record, and the still-pending complaint from Michael DePasquale. Given the paper’s lengthy history of reporting on the junctures where crime and nightlife intersect, whether benignly or otherwise, it seemed necessary to follow up on that information. Under similar circumstances, we would have done the same with any club.

Believe it or not, I’m sorry the Talking Head is closing, and I sincerely hope that the folks behind it can re-establish a sustainable version of the club elsewhere. For better or worse, we will continue to write about it then, too.