By Van Smith

Published in City Paper, Dec. 19, 2007

David Schmidt is president of a marine-supply company in Hanover, Pa., who keeps a boat in a slip at Canton Cove Marina, where Linwood Avenue ends at the harbor. As he approaches the marina gate and gangway on Sept. 12, he notices me and another paddler holding back gags as we nose our kayaks toward the storm water that empties into the harbor beneath the waterfront promenade in front of two condominium buildings there. Schmidt sees us look down at the gray-colored water we’re floating in, into the darkness of the tunnels where it’s coming from, and then back down at the water.

“It’s raw sewage coming out of the storm drain,” Schmidt says flatly as he walks along the dock. “I’m down here all the time for the last five years, and it’s been going like that the whole time. It’s not always this bad, but it’s always bad. God forbid anybody fall in. You should see it when it rains.”

There’s been no rain to speak of for weeks, and yet here is enough sewage to turn the water at the marina a striking shade of gray and to thoroughly stink up the surrounding blocks. It’s entering the harbor out of a drain outlet, or “outfall,” that’s designed to funnel runoff from city streets and pavements when it rains, not the waste water that the city’s sewage system funnels to its water treatment plants. If there had been a good, hard rain, then one might expect some sewage in the storm drain; the sewer pipes running down streambeds tend to get hit by large objects in storms, sometimes getting blown open and causing nasty messes downstream. But there had been no storm. There had to be some other explanation.

Schmidt keeps talking. He’s indignant but resigned, complaining that he pumps out his boat sewage so it won’t get in the Chesapeake Bay, as the law says he must, and the city should, too. But apparently, he concludes, the city would rather keep paying fines than obey the law.

Schmidt has many ways to complain about the odor, perhaps because that’s the main topic of the conversations he has with others who rent slips here. “I got my boat sealed up so I can go down below and get away from it,” Schmidt says, and points to other boats similarly protected. “But you never really can. That restaurant”–he points at the nearby Bay Café–“keeps its patio awnings zipped up on this side because of it. That pool next to it [at Tindeco Wharf] is hardly used, most of the time. Look at all those condo windows,” he says, gesturing at the Canton Cove building. “Nice weather, but they’re closed up tight. Same thing. It’s the smell.”

Schmidt walks onto his boat and goes below, and we glide away in our kayaks, marveling that fish are jumping just 50 yards away from the foul outfall. What’s more, a quarter-mile away, at the bulkhead of the Korean War Memorial Park, men are fishing for those fish.

The Linwood Avenue outfall has been polluting the harbor with sewage, on and off, for a long time. Schmidt’s account confirms what I’ve occasionally observed firsthand while kayaking or walking by here since the late 1990s. The federal Clean Water Act calls for all U.S. waters to be returned to swimmable and fishable conditions, and while fish sometimes jump near here, swimming, while never advisable, would at times be suicidal. So the next day, I call the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Justice, which enforce the Clean Water Act, to find out whether or not the sewage coming into the harbor from under Linwood Avenue is somehow allowed. After a couple of short back-and-forths about what was observed, it quickly becomes clear that it is not.

“We’d be very interested in investigating,” adds Angela McFadden, a high-ranking pollution enforcement officer at the EPA, in a Sept. 24 phone conversation, “because I am not aware of any continuous discharges of untreated sewage going on.”

The EPA and the DOJ are the plaintiffs, along with the Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE), in a Clean Water Act lawsuit in U.S. District Court filed against the city of Baltimore a decade ago over its illegally leaky sewer system. Five years ago, a “consent decree” was entered in the matter. Under the decree, the city must spend almost a billion dollars over 14 years, starting in late 2002, to get its sewer system into compliance with the federal Clean Water Act. So far, with less than a decade to go, the city has spent nearly $260 million and has repeatedly raised water-and-sewer rates to pay for it.

A few weeks pass of phone tag punctuated by short conversations with the EPA and DOJ, and as September turns to October, I file a request to look at the EPA’s consent-decree records and periodically return to the Linwood Avenue outfall. The scent of sewage becomes less intense over time, but it still has that unmistakable reek, especially right after it first starts to rain and whatever’s pooled up in the pipes during the dry weather gets flushed out.

Meanwhile, the city’s 311 system for logging citizen complaints and service requests steadily registers calls from along Linwood Avenue as it heads north from the waterfront into the city. The 311 system is alerted seven times about sewer odors along the Linwood corridor during September, and another nine times for the 12 months prior to that. Some of the calls are quite specific about the source, describing “a strong sewer smell coming from the storm drain in the street,” for instance, or “a very strong sewer odor coming from the inlet.” On Election Day, Sept. 11, the day before Schmidt talks to us in our kayaks, someone reports that it “smells like sewage inside and out” of a house on Linwood, two blocks north of the outfall.

Citywide, 31 other complaint calls came in to 311 operators in September about sewer odors. “There is a strong sewer odor in the area,” the city is notified by a caller from the Northwest Community Action neighborhood, on the west side near Walbrook Junction. Another caller points out that there is a “strong odor of sewage in the air” at East North Avenue and Broadway, near the Great Blacks in Wax Museum. A “bad sewer smell” is reported at Gay and Lombard streets, a block off the harbor downtown, and a “very powerful sewer smell” is noted in Waverly. “A very strong sewage smell is coming from the pond” in the woods behind Uplands, another caller notes, giving the location where Maiden Choice Run begins its rough-and-tumble journey through Southwest Baltimore before it reaches the Gwynns Falls just above Carroll Park. The list goes on.

Aside from the sewage stench rising from below the streets, the 311 system also logged a myriad of complaints that sewage was flowing in city streets, sidewalks, alleys, and into storm drains in September, which was an extremely dry month with less than half an inch of rain. As the weeks passed, the city responded to a total of 19 calls described as reporting “sewer overflows” and “sewer leaks,” and numerous other calls that described sewage flowing in the streets. When sewage runs on the streets, it enters storm drains and, ultimately, enters the Chesapeake Bay. How to estimate that flow–especially at a storm-drain outlet like the one at Linwood Avenue, which is designed to be partially submerged in the Patapsco River’s tides–is anybody’s guess.

The consent decree requires the city of Baltimore to estimate the amount of sewage released in leaks the city deems reportable, so if anyone’s trying to guess how much Baltimore City sewage is leaking, it’s the city’s Department of Public Works. It looks like DPW is lowballing it.

Whenever an “unauthorized discharge of wastewater” from the city’s sewage collection system into “any waters” of the United States, the consent decree dictates that a written report must be provided to EPA within five days. In the report, the city must describe the cause, duration, and volume of the flow, as well as “corrective actions or plans to eliminate future discharges” at the site and “whether or not the overflow has caused, or contributed to, an adverse impact on water quality in the receiving water body.”

Once DPW estimates the amount of sewage that leaked and reports it, the city is subject to fines based on the number of gallons of sewage that the city says leaked. Since January 2003, EPA records reflect the city has been levied fines totaling $416,200 (the payments are split evenly between EPA and MDE) for 255 reported leaks.

The sewer-leak reporting also forms part of the quarterly reports that the city must prepare and submit under the consent decree, to keep all the plaintiffs up to date on progress in improving the sewer system’s performance. The tally of reported leaks listed in the quarterly reports since December 2002 is 419, releasing a total estimate of nearly 190 million gallons. The smallest reported leak was 12 gallons lost to Western Run, which joins the Jones Falls near Mount Washington, on a rainy day in April 2004. The largest was the July 2004 bulkhead failure at Braddish Avenue behind St. Peter’s Cemetery in West Baltimore, which released a rush of sewage into the Gwynns Falls initially estimated to be 36.25 million gallons, though online MDE records put the guess at 1.5 million gallons.

The trend on paper has been fewer leaks reported as the consent decree progresses, with 143 reported for 2003 and 72 reported for 2006. By the end of June this year, summary details on 31 leaks were included in the quarterly reports, so 2007 appears headed for an even lower total.

As of Nov. 7, when I went to Philadelphia to review EPA’s consent-decree files, the city of Baltimore had not notified the agency of any reportable sewer leaks occurring in September 2007. There were some reported in August and some in October, but none in September. Thus, whatever spewed raw sewage out into the harbor at the end of Linwood Avenue in September, and whatever prompted citizens citywide to lodge complaints about sewer leaks, overflows, and odors over the course of that very dry month, it wasn’t sewer leaks reported by the city under the consent decree. It must have been something else.

Oddly, the 311-calling public appears to be more attuned to sewage leaking in Baltimore City when the leaks aren’t reported under the consent decree than when they are. A year before, in September 2006, when at 7.5 inches there was nearly twice the historic average rainfall for that month, the situation was reversed. The city reported five sewer discharges totaling 39,255 gallons, occurring in Waltherson, Grove Park, Cherry Hill, Violetville, and the state’s Juvenile Justice Center on Gay Street downtown. But on 311, not a single call about a sewer leak or overflow came in all month long.

“The consent decree requires the City to report releases from the collection system that reach receiving waters or storm sewers,” EPA spokesman David Sternberg writes to City Paper in a Dec. 7 e-mail. “It does not require the City to report releases that don’t meet these criteria (i.e., basement backups).”

Perhaps September’s citywide sewage funk that had residents reaching for their phones–and sewage contaminating the marina where Schmidt keeps his boat–was due to something as routine and hard to stop as a whole lot of basement backups occurring during what amounted to a drought. And perhaps the absence of 311 sewer-leak complaints in September 2006, when heavy rains prompted the city to report one big leak and grease clogs caused four smaller ones to be reported, is attributable to the fact that the leaks the city detected were in areas where residents didn’t see or smell them.

But one thing is clear, based on the September flow out of the Linwood Avenue outfall: Sewage from Baltimore City is getting into the storm drains and, thus, into the bay–a lot more sewage than the amounts being reported by the city under the consent decree.

“The harbor is being polluted with sewer overflows, especially at Linwood Avenue,” Phil Lee explains. As a founder of the Baltimore Harbor Watershed Association and an engineer, he’s being asked to comment about the Linwood outfall and its impact, and he says he’s spoken with environmental authorities about it over the years. At some point, he says, he was told that an “illicit connection into the storm-drain system upstream” was contributing to the problem. “I don’t think they’ve fixed it,” he observes, adding that “it’s still like Old Faithful.”

Lee’s not the only one who’s been keeping track of the Linwood Avenue outfall. A man whom Lee calls “a one-man army” in the cause of tracking sewer problems, Guy Hollyday, has been telling authorities about it for years.

Hollyday’s group, the Baltimore Sanitary Sewer Oversight Coalition, targeted the Linwood Avenue outfall as an “acute” sewer problem–one of three it had identified citywide–during a meeting held for city officials at Loyola College in November 2005. The group, formed in 2000 when four Baltimore watershed groups combined and coordinated their ongoing efforts to keep sewage out of city streams, issued its annual report for 2006 in May this year, updating the situation.

The report pinpointed an illegal sewer connection to the storm-drain system at the site of Pompeian Inc., an olive oil bottling company located on Pulaski Highway in East Baltimore, about two miles away from the outfall as the crow flies. It’s not clear whether the illegal connection has anything to do with Pompeian or if it just happens to meet the storm drains under the company’s property; attempts to contact Pompeian for comment were unsuccessful. Based on information from the city, however, the group’s summary explained that 300 feet of sewer pipe upstream had been lined to try to keep the sewage from entering the storm-drain system there, but as of September 2005, with sewage still entering the storm drain, the city had resolved to replace the next section of sewer downstream, too.

“It’s still not fixed, as far as I know,” Hollyday says over lunch at nearby Kiss Café in late November.

He’s right. In a Dec. 10 e-mail, DPW spokesman Kurt Kocher identifies the illegal connection at the olive oil company’s property, and explains that “the city is awaiting this company’s final plan for plant expansion,” which “will include a new proposal for the relocation of the sewer line” that’s been causing problems. “The city has continued to keep [MDE] informed on the status of this project,” Kocher adds, though apparently EPA has not been in the loop. Nothing about it appeared in the voluminous EPA files reviewed by City Paper, and the EPA’s Angela McFadden had not heard of the sewage appearing at the Linwood Avenue outfall, much less where it might be coming from.

In all likelihood, sewage will from time to time continue to contaminate the harbor at the Linwood Avenue storm-water outfall. Citizens, whose rising water and sewer rates are paying for the billion-dollar sewer-system overhaul, will endure the fouled water and reeking air until the sewer is fixed at Pompeian Inc. If the sewage still flows then, the city likely will seek out and fix other sources of sewage in the storm drains as more years pass. Perhaps it will turn out to be an never-ending battle, and there always will be sewage flowing into the harbor beneath Linwood Avenue, for as long as people flush toilets and have basement backups in Baltimore.

But none of that changes the course of progress. DPW is deeply proud of its work so far under the consent decree, and is bound to stay that way. “As of this date,” Kocher wrote in his Dec. 10 e-mail, “all but 5 of [39] construction projects [required under the consent decree] have been completed and 54 engineered [sewage] overflow structures have been eliminated.” Up next are sewershed studies and sewer flow monitoring across the city, he continued, which aim to root out the sources of unpermitted sewage discharges. “The current estimate of the program at $900 million,” Kocher concluded, “continues to be a reasonable estimate at this time,” adding that once the upcoming studies are completed “the City will be able to better refine that estimate.”

Because of the progress that has already been made, and because of more progress that’s required before the consent decree expires, Lee believes in swimmable, fishable harbor water by 2020–that’s what the law has set out to do. His optimism is commendable and was likely shared widely in 1972, when the original Clean Water Act first passed, calling for swimmable, fishable waters by 1983. But 2020’s a long time away, and hundreds of millions of dollars still has to be spent in a little less than a decade on sewer improvements. Lee seems truly to believe it’s doable, and he sees the sewage flowing beneath Linwood Avenue, while a longstanding condition, as a temporary one requiring patience before the city finally puts an end to it.

When it comes to water-quality issues, Darin Crew has to be nearly as adept at understanding sewersheds as he is at understanding watersheds. He came to Baltimore to take a job at the Herring Run Watershed Association, aiming to improve water quality in the Northeast Baltimore watershed, which is a tributary to Back River in Baltimore County. That was 2003, and in February of that year, the Herring Run hosted what was immediately billed as one of the worst sewage spills in city history. An estimated 36 million gallons of sewage was released after two massive sewer lines embedded in the stream became blocked.

Four months later, in June 2003, an estimated 35 million gallons of sewage leaked out of a damaged manhole along Herring Run, poking a hole in the largest-in-city-history theory about the first one. The following May and July brought two more 30 million gallon-plus gushers at Braddish Avenue, affecting the Gwynns Falls. For Crew, knowing about the weak links in the sewer system in Herring Run’s drainage area was to be a major part of his new job.

“It’s right down here, directly beneath this bridge,” Crew says as he pulls up in his pickup truck. The Mannasota Avenue bridge spans Herring Run, connecting the Belair-Edison and Parkside neighborhoods, and Crew promises to show me and a City Paperphotographer that sewage is running out of the storm drain constructed in the bridge foundation. We follow Crew as he scrambles down the stream bank and goes under the bridge. Concrete was used to channel Herring Run as it passes beneath the bridge, and the clear water coming out of the storm drain splashes on it and runs, pooling here and there, into the clear running stream. There’s no odor of sewage.

“It doesn’t always smell,” Crew explains. “You can tell that sewage is a likely component of what’s coming out of here by the gray scum that collects on the surfaces wherever the water is for any period of time. It’s just gray scum. Other than that, you can measure ammonia in the water. That’s a pretty good indicator. And the ammonia levels are always pretty high here. This flows about a gallon a minute, and that works out to be 60 gallons an hour–you do the math. It’s a constant flow, except when it rains. And this low-level kind of thing, by itself, doesn’t really do much damage, water quality-wise, given all that’s already getting into the stream. But it’s still a problem.”

“What about that one over there?” the photographer asks, pointing across Herring Run to another outfall coming out of the opposite stream bank. “I don’t know, let’s go see,” Crew suggests. Again, the water is clear. But this time the sewage odor hits while approaching the opening. “Whoa, that’s definitely sewage,” Crew says of the smell. But there’s no telltale gray scum. Turns out, there’s another outfall beneath the one the photographer spotted, and down there–it takes some effort and contortions to see it–there’s plenty of gray scum forming as the clear storm-drain water courses out of the pipe and into Herring Run.

“Taken all together,” Crew concludes, “these types of small, steady sewage leaks do become a serious water-quality problem. It’s not as serious as the 30 million gallons that came down here a few years ago, but it’s a problem, and I think it’s about time we kicked up the enforcement effort on this kind of thing.” He shows us one more example, under a bridge on Hillen Road next to the Mount Pleasant Golf Course, and gets back to work.

On Nov. 30, the photographer and I go to the 4500 block of Fairfax Road in West Baltimore’s Windsor Hills, looking for a plumber. A&A Plumbing is listed at an address on this block, and, since no one from the business had returned a phone message, we came to knock on the door. Once there, we found three men in baseball caps standing beside three pickup trucks, backed up toward the entrance. They know nothing of the plumber listed at that address.

“What, are you bondsmen?” one asks, and everyone laughs.

I explain that we’re almost as unwelcome, under most circumstances: the press. But when it becomes clear that the story has to do with the city’s efforts to fix its chronically leaky sewer system, and that this area has a particularly rough history of sewer problems, and that a plumber’s anecdotes of Windsor Hills sewage nightmares was sought, the three men grow friendly and relaxed. One, a 40-year-old truck driver from Randallstown who introduces himself as Rick Edwards, steps up and starts talking.

“I keep my boat down at the harbor,” Edwards explains, “at Canton Cove Marina at the end of Linwood Avenue. Been keeping it there like four or five years, and there’s sewage coming out of the storm drain there, stinking things up so bad I hardly even use my boat anymore. Can’t even go sit on your boat down there, can’t entertain or have friends down, because it smells so bad.” The infamous outfall’s reputation apparently remains intact all the way across town in Windsor Hills.

We take leave of the men to check out the sewer-main stacks protruding up from the streambed next to the Windsor Hills Conservation Trail, at the end of the block. We return a half-hour later to announce there’s no sewer odor, but the water coming out of the storm drain shows evidence of the likely presence of sewage: gray scum on the rocks and concrete where the water runs.

“The boats down at the marina,” Edwards says, “you have to clean gray scum off of the bottom of them, just like the stuff you see on them rocks. It’s the same stuff. I’ve had it scrubbed and cleaned off, and it looks like it grows off the bottom of the boat, literally. It’s just this muck.

“There’s sewage coming out all over. But what’re you gonna do? I talked to a city worker about it, he said the pipes are so old, it’s just always going to leak, and they’ll just keep on trying to catch up with them all. The leaks up here, on this street, they don’t go to Linwood Avenue, but it all ends up in the same place eventually.”

Edwards is standing seven miles away, in a straight line, from the Linwood Avenue outfall. Sewage that leaks here travels downhill to the end of Fairfax Road, where it drains downstream into the Gwynns Falls and, having joined up with more sewage-laden water as it goes, reaches the Middle Branch of the Patapsco River right near the BRESCO waste incinerator. From there, it joins the Patapsco’s North Branch–better known as the Baltimore harbor–at Fort McHenry. Right across the harbor from Fort McHenry is the Canton Cove Marina, where Edwards wishes he no longer kept his boat, and where David Schmidt complained in full three-part harmony that September day to two kayakers about the powerful dose of sewage coming out of the Linwood Avenue outfall. Everything, as they say, is connected.

“It’s gotten to the point where I don’t even want to be on the bay at all,” Edwards says of what the sewage, and pollution in general, is doing to his boating habits. “At this point, I think I’d rather be in Ocean City, any day.”

We say goodbye and drive up the hill from Fairfax Road onto Talbot Street, pulling over to speak with a gentleman raking leaves on the curb. “Sure, I know about the sewer problems over the years,” he says. “They did a lot of work trying to fix them in the ’70s and ’80s, and they did more in the ’90s. Used to hear the heavy machinery down in the Gwynns Falls, and now they’re doing more under the streets here. As for the details, I’m probably not the best person to ask. That house right there”–and he points to one across the way–“David Carroll lives there. He’s some kind of environmental expert. You should ask him.”

“David Carroll,” he announces, when he picks up the phone at his Towson office in early December. Carroll is the director of the Baltimore County Department of Environmental and Resource Management, an agency that manages a sewage system under a consent decree much like Baltimore City’s, which went into effect in 2005 and involves the same plaintiffs. He’s held similar high-level public positions as an environmental manager in Baltimore City and in state and federal government over the years, including a stint as MDE secretary under Gov. William Donald Schaefer in the 1980s and ’90s. This impressive résumé qualifies Carroll, in the words of his neighbor in Windsor Hills, as “some kind of environmental expert.”

But Carroll is also a longtime resident of Windsor Hills, where sewer leaks have historically plagued the city’s underground pipes, and that gives him some personal perspective on the impact of sewage on city neighborhoods, and the challenges of making improvements to sewer systems.

“Frankly, we haven’t tracked it all that closely,” Carroll says of the Windsor Hills community’s sewage-leak monitoring efforts. “We got together and started the Windsor Hills Conservation Trail, there at the end of Fairfax Road, and people out on the trail have been reporting leaks there for the last 10, 15 years. There have been lots of leaks reported over the years, but it’s been pretty sporadic, given the fact that we’re not really monitoring it in an organized fashion.

“The community association in the neighborhood has been working with the Windsor Hills Elementary School,” he continues, “to use those sanitary stacks sticking up in the stream along the conservation trail as education tools. And that’s important, because the neighborhood kids actually do swim in the Gwynns Falls. And, in fact, the effort’s working. There was an environmental festival for the schoolchildren down along the stream, and some kids jumped into a pool of water in the Gwynns Falls, and another kid said, `Get out of there! There are fecals all in there!’ He was talking about fecal coliform, and that kid understands it’s in the water and it’s dangerous, and he’s telling other kids that. That’s good.”

Carroll has heard of the ongoing stench and foul water coming out of the Linwood Avenue outfall–“that one’s pretty infamous,” he says–but he’s not convinced, even with all the expensive sewer reconstruction and extensive efforts to curtail the sewage entering the harbor, that the harbor will ever improve to the swimmable, fishable standard set forth in the Clean Water Act.

“When we get all the pipes working as they should, we’ll still have all this organic matter in the system–crap from geese and dogs and cats, dead animals, the grease and oil and food scraps and trash that gets washed off the streets, all the rest of it. And we’ll still have a problem. And then what are we going to do? But the first thing you got to do is get the human stuff out of there. And as this gets done, there will be major improvements in the amounts of raw sewage going into our streams.

“As for the city,” Carroll continues, “it’s just this network of really old sewers, and there’s a lot to do. Blockages occur in the main sewer lines, and the resulting backups usually cause leaks–that, or a standing [sanitary] stack gets severed, or a pumping station fails. Grease collecting in the lines and clogging them–that’s a big problem. The way we do it, every time that happens, if there’s anything at all that leaks–anything, it doesn’t matter if it’s a gallon or not–we have to report it to MDE and EPA, even if it doesn’t reach the waters of the state. It’s anything that leaks. Zero tolerance, that’s the threshold.

“But it’s not the amount of sewage spilled that matters,” Carroll emphasizes. “It’s the impact it has on water quality on an ongoing basis. And the big overarching context here is this–you want us to get swimmable and fishable waters, but how do you do that? Where has it worked? I’ve got sunfish in the Gwynns Falls, but is it really ever going to be safe to swim in it? Because there’s still going to be a lot of things that make the water yucky that are still going to be there, after all this work on the sewers is said and done. And that’s what the public, who’s paying for all of this, doesn’t seem to understand. It’s not the message they’re getting. They’re hearing that all this billion dollars of sewer improvements is going to make the harbor clean, but that’s simply not the case.”

City Paper awaits the outcome of the investigation EPA says it’s conducting into the sewage that comes out of the Linwood Avenue storm-drain outfall. Also pending are full responses from EPA, MDE, DPW, and DOJ to two November letters from City Paperabout a variety of consent-decree compliance issues that jumped off the pages of the EPA’s records. As a result of numerous 311 complaints describing what sound very much like sewage leaks that are discharging into city streets, gutters, and storm drains, and yet aren’t reported under the consent decree, a major question was whether the city has been routinely failing to report leaks as required. DPW provided a partial response in a Dec. 7 e-mail.

“The majority of the [311] complaints listed in your letter pertain to sewage in basements,” the statement reads in part. “These types of complaints are not applicable to reporting under the consent decree. At some locations listed, the 311 complaint code was characterized as a sanitary sewer overflow, however, there was no associated report sent to the regulators. This is due to a variety of reasons,” but in most cases “it appears that [DPW] corrected certain problems but did not observe a reportable discharge.”

In essence, the statement says DPW reports all sewer leaks, as required, without exception. Yet the Baltimore Sanitary Sewer Oversight Coalition’s Guy Hollyday says he’s been pointing out ongoing sewer leaks to DPW for years, and DPW’s been confirming that they exist and continue leaking, and yet many remain to be fixed. The group’s 2004 annual report, for instance, states that during that year DPW confirmed the existence of 17 ongoing sewer leaks around the city, yet they weren’t repaired. Some, Hollyday says in late November, still haven’t been.

The last time I checked, on the evening of Dec. 10, turbid, brown, debris-laden water was coming out of the Linwood Avenue storm-drain outfall, but it didn’t stink of sewage. The next day, Rick Edwards, the Randallstown truck driver, calls. That gray scum is building up on the hull of his boat, he explains, and he repeats that he’s about had it with all this sewage in the harbor.

“It smells like sewage half the time,” he says. “Everyone is talking about it–it’s a common issue.”

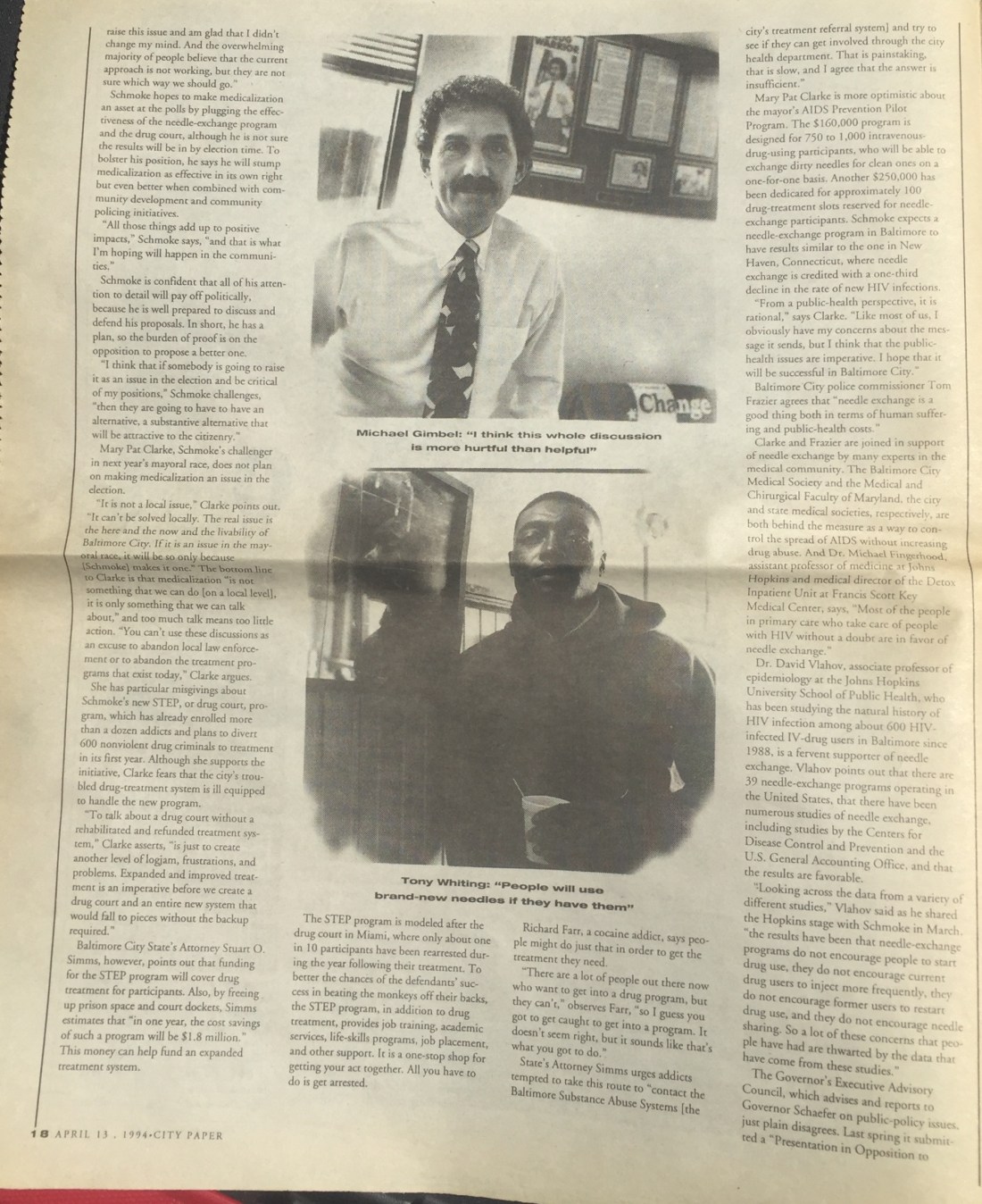

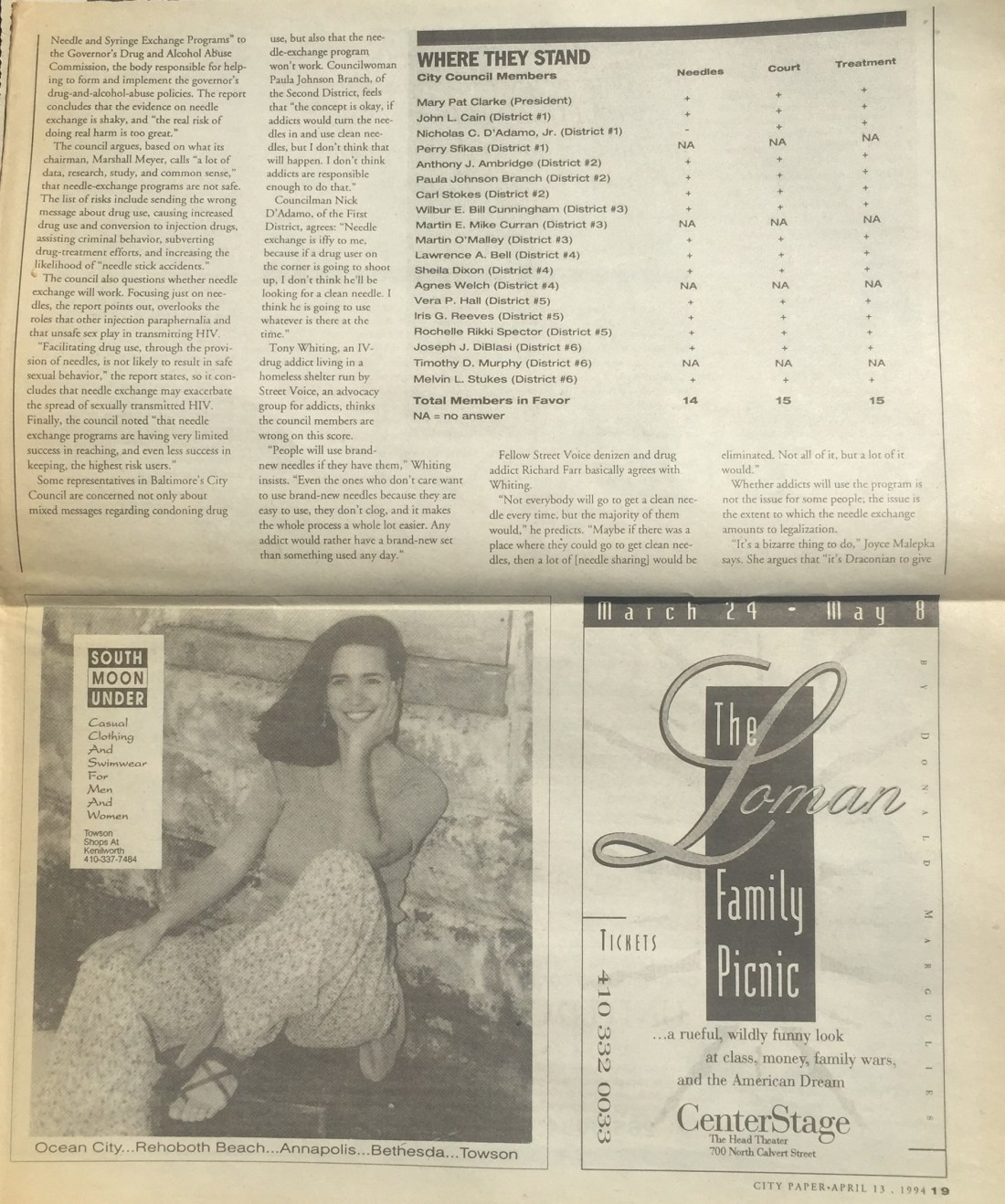

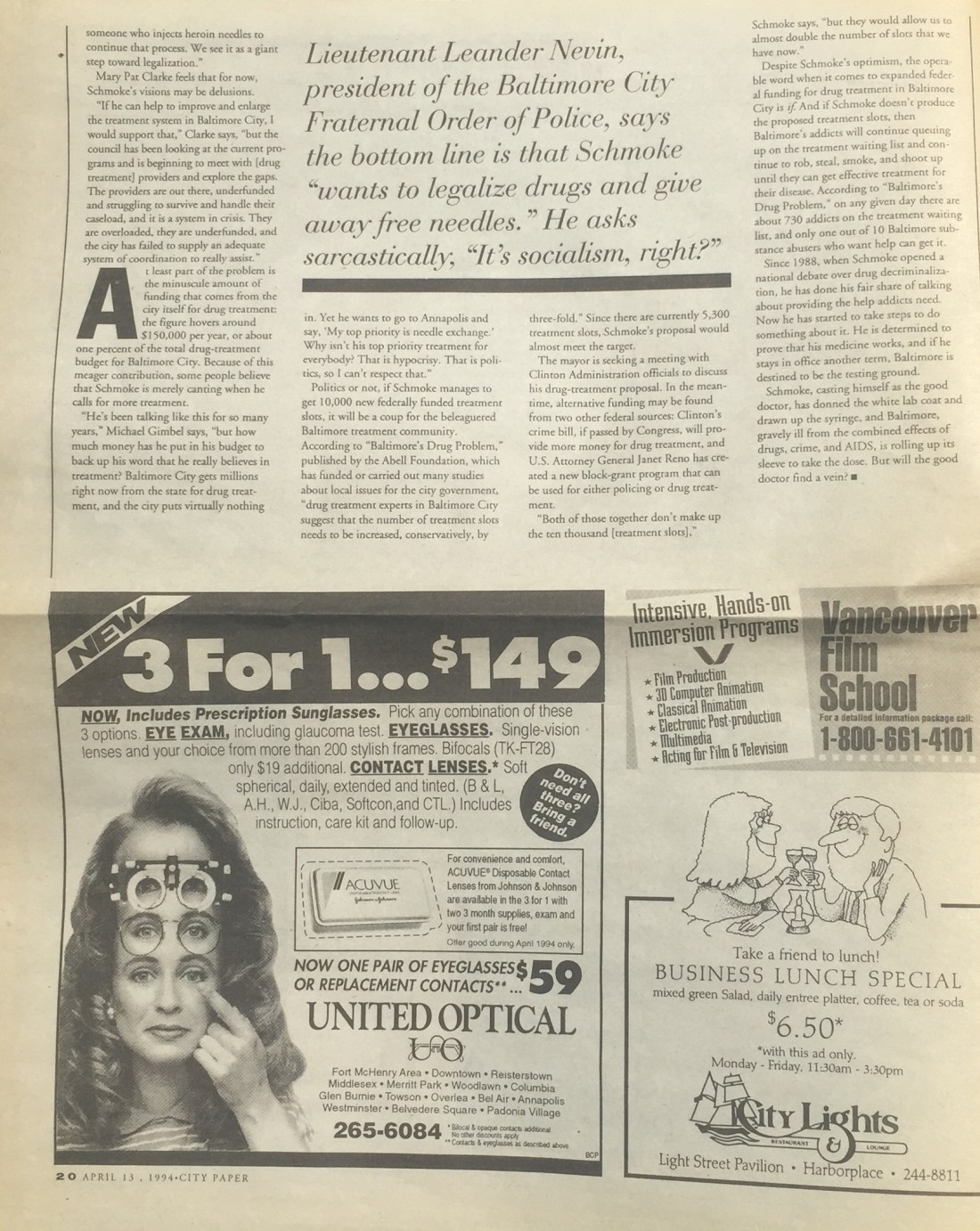

By all appearances, the stench in the harbor is not going to go away anytime soon, so everyone can still go on talking about it until it does–be that 2020, or beyond.