By Van Smith

Published in City Paper, Apr. 13, 1994

With two recent political and legislative breakthroughs for Mayor Kurt Schmoke, Baltimore is becoming a model city for drug reform. In March, a $2.3 million federally funded Substance Abuse Treatment and Education Program (STEP), or “drug court,” began diverting nonviolent drug criminals from prisons to treatment programs. And on April 5, the Maryland State legislature passed a bill exempting Baltimore City from certain drug-paraphernalia laws and approving funding for a needle-exchange program called the AIDS Prevention Pilot Program. In a reversal of his earlier stance, Governor William Donald Schaefer supported the bill and is expected to sign it. The success of these two initiatives is a major priority for Schmoke, who is out to prove that what he calls a “medicalization” approach is the best solution for our multiple woes of drugs, crime, and AIDS.

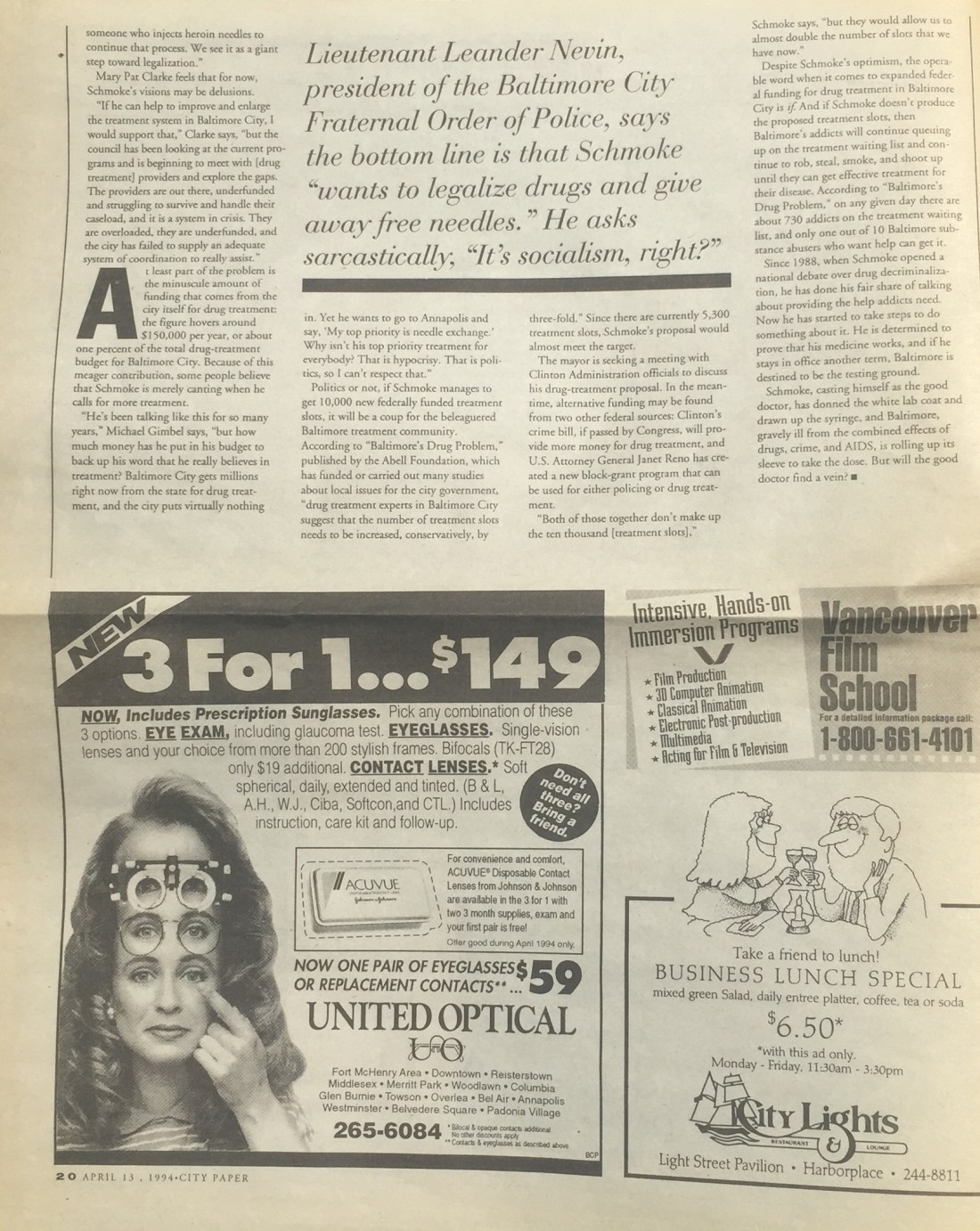

The drug court and the rest of Schmoke’s immediate drug-reform measures appear to enjoy wide support here in Baltimore City. The City Council is almost unanimously behind the mayor’s initiatives. Baltimore’s public-health and drug-treatment providers, who stand to gain funding and stature from the initiatives, also generally approve of them. The new police commissioner, Tom Frazier, says needle exchange, the drug court, and expanded treatment will make his job easier. And of course Baltimore’s heroin and cocaine addicts – who make up about six percent of the population, according to Bureau of the Census figures – are all for it.

In fact, one gets the impression that the mayor’s local drug-reform agenda has been falling into place with relative ease. People tend to see needle exchange, the drug court, and expanded treatment as almost clinical prescriptions for treating the symptoms of the drug crisis.

It is Schmoke’s national long-term drug policy, with its overtones of decriminalization, that has attracted strong and vocal opposition.

By now, everybody knows that Schmoke advocates some form of drug decriminalization. To a lot of people, that strategy sounds so radical on the surface that they aren’t very interested in the details. For example, Lieutenant Leander Nevin, president of the Baltimore City Fraternal Order of Police, says the bottom line is that Schmoke “wants to legalize drugs and give away free needles,” and asks sarcastically, “It’s socialism, right?”

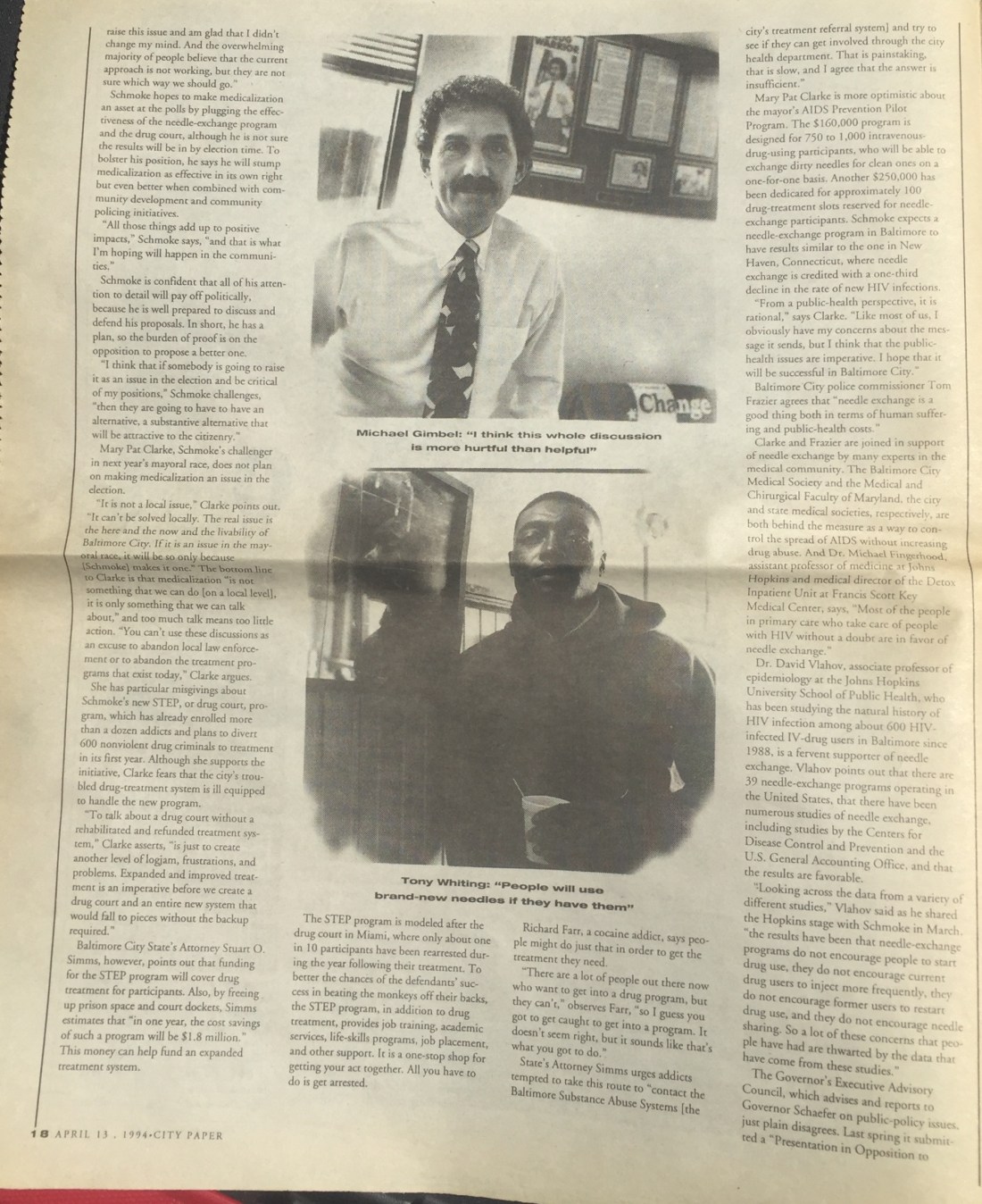

To Michael Gimbel, director of the Baltimore County Office of Substance Abuse, the details of decriminalization are insignificant compared to the impact of even talking about it. He sees a direct correlation between rising drug use in high schools and the whole debate over decriminalization, which Schmoke has persistently publicized for six years now.

“I think this whole discussion is more hurtful than helpful,” Gimbel says. “I have to deal with the kids today who believe in legalization only because the mayor or the rap group Cypress Hill said so. For the last ten years we have seen major decreases [in drug use] and changes of attitude. Now all of the sudden these kids are changing the way they looking at [legalization]. I have to deal with that, and I blame it on the legalization debate.”

Barring some undetected tectonic shift in public opinion over the last six years, Nevin and Gimbel are right in line with most Marylanders’ opinions of legalization. In 1988, The Evening Sun contracted a public-opinion research firm to survey a random sample of Marylanders over 18 years old to ask them whether they support drug legalization. The results were basically the same for Baltimore as for the whole state: less than 20 percent were for legalization, and more than 70 percent were opposed to it.

In spite of this opposition, Schmoke has high hopes for his long-term, national strategy, which he clearly does not want associated with the term legalization.

“My approach is not legalization, that is, the sale of drugs in the private market,” he told an audience of doctors and nurses at the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health in March. Rather, he proposes lifting a corner of the current blanket prohibition on illegal drugs by drawing addicts into the public-health system, where they could be maintained, if necessary, using drugs made available through a government market.

“The government, not private traffickers, would control the price, distribution, purity, and access to particular substances, which we already do with prescription drugs,” Schmoke told the audience. “This, mind you, would take most of the profit out of street-level drug trafficking, and it is the profits that drive crime. Addicts would be treated and, if necessary, maintained under medical auspices. In my view, street crime would go down, children would find it harder, not easier, to get their hands on drugs, and law-enforcement officials would concentrate on the highest echelons of drug-trafficking enterprises.”

Schmoke’s zeal for reform is coupled with a hardened distaste for drug prohibition.

“Drug prohibition is a policy that has now turned millions of addicts into criminals, spawned a huge international drug-trafficking enterprise, and brought unrelenting violence to many of our urban neighborhoods,” Schmoke said. “It was a flawed strategy when it began, and it is still a flawed strategy now.”

Legalization or not, the mayor’s approach is roundly dismissed by people who think any fiddling with drug prohibition would, as a sociobiologist might say, damage the antidrug “chromosomes” that have been grafted into society’s DNA sequence over the last few generations. One such person is Dr. Lee P. Brown, the director of President Clinton’s Office of National Drug Control Policy. In a statement on drug legalization last December, after U.S. Surgeon General Joycelyn Elders suggested that legalization would reduce crime, Brown commented that “[a]ny change in the current policy of prohibiting drug use would seriously impair antidrug education efforts, drug-free community programs, drug-free workplace programs, and the overall national effort to reduce the level of drug use and its consequences.”

Local opposition to Schmoke’s call to change national drug laws is every bit as pointed as the Washington establishment’s. Gimbel protests that decriminalization “is a real intellectual pipe dream, and it scares me because the mayor is very articulate in selling this program.” City Councilman Martin O’Malley, of the Third District, thinks it “just amounts to so much more intellectual bullshit.” Joyce Malepka, founder of the Silver Spring antidrug lobbying group called Maryland Voters for a Responsible Drug Policy, says, “There is no intellectual argument about legalizing drugs because anyone who is that short-sighted isn’t really experienced, and if that is the case, then there is certainly no business talking about it.”

One objection that Schmoke’s medicalization opponents make is that a prescription-based drug-treatment system for addicts would be ripe for abuse. Steve Dnitrian, vice president of the Partnership for a Drug-Free America, in New York City, argues that legal drugs are already abused and a wider array of them would lead to greater use and abuse.

“Take a look at the drugs that are already regulated medically, such as Valium,” Dnitrian says, by way of illustration. “Are they abused? Heavily. Medicalization would be the same thing. You would just be adding a couple of more flavors to the vast array of products we have right now to alter reality. If you make available a product that is not readily available, it is going to get used. Even people who favor decriminalization acknowledge that drug use would go up dramatically.”

Still, Schmoke has so far managed to buck the antidecriminalization establishment and remain in office. How has he done it?

One explanation is that his drug-reform strategy is multi-faceted and comprehensive, so many who oppose him on decriminalization or needle exchange agree with many of his other drug-reform ideas. For instance, his crusade for drug treatment on demand and the creation of drug courts is lauded from all corners, including by Malepka and Gimbel, President Clinton, and the antidrug advertising venture Partnership for a Drug-Free America.

Schmoke hasn’t got this far by smart policymaking alone, however. Part of it was political drive: he is on the line with this medicalization talk, so he has been campaigning hard to prove his is right; if he can’t, he risks losing legitimacy with the public. Frank DeFillipo, a political columnist for The Evening Sun, says, “Schmoke has a lot to defend. He is going to have to go out and defend that issue in the mayoral race, and there are compelling arguments against what he is advocating.”

On the mayor’s side are a significant number of individual legislators, doctors, lawyers, judges, and religious leaders – powerful people with connections to organizations that can effect change. Schmoke feels that the average voter may also be coming around to agree that we need a new strategy against drugs, crime, and AIDS, and that medicalization should be given a sporting chance. Depending on how he plays this issue during the upcoming mayoral campaign, Schmoke may bet his future in political office on that perceived trend. He has been making every effort to swing the Zeitgeist around. Given the poll-pending strength of his supporters, he just might be able to do it.

“My sense is that the majority of Baltimoreans may disagree with my conclusion about the need for medicalization and decriminalization,” Schmoke acknowledges, “but that they agree that I should raise this issue and am glad that I didn’t change my mind. And the overwhelming majority of people believe that the current approach is not working, but they are not sure which way we should go.”

Schmoke hopes to make medicalization an asset at the polls by plugging the effectiveness of the needle-exchange program and the drug court, although he is not sure the results will be in by election time. To bolster his position, he says he will stump medicalization as effective in its own right but even better when combined with community development and community policing initiatives.

“All those things add up to positive impacts,” Schmoke says, “and that is what I’m hoping will happen in the communities.”

Schmoke is confident that all of his attention to detail will pay off politically, because he is well prepared to discuss and defend his proposals. In short, he has a plan, so the burden of proof is on the opposition to propose a better one.

“I think that if somebody is going to raise it as an issue in the election and be critical of my positions,” Schmoke challenges, “then they are going to have to have an alternative, a substantive alternative that will be attractive to the citizenry.”

Mary Pat Clarke, Schmoke’s challenger in next year’s mayoral race, does not plan on making medicalization an issue in the election.

“It is not a local issue,” Clarke points out. “It can’t be solved locally. The real issue is the here and the now and the livability of Baltimore City. If it is an issue in the mayoral race, it will be so only because [Schmoke] makes it one.” The bottom line to Clarke is that medicalization “is not something that we can do [on a local level], it is only something that we can talk about,” and too much talk means too little action. “You can’t use these discussions as an excuse to abandon the treatment programs that exist today,” Clarke argues.

She has particular misgivings about Schmoke’s new STEP, or drug court, program, which has already enrolled more than a dozen addicts and plans to divert 600 nonviolent drug criminals to treatment in its first year. Although she supports the initiative, Clarke fears that the city’s troubled drug-treatment system is ill equipped to handle the new program.

“To talk about a drug court without a rehabilitated and refunded treatment system,” Clarke asserts, “is just to create another level of logjam, frustrations, and problems. Expanded and improved treatment is an imperative before we create a drug court and an entire new system that would fall to pieces without the backup required.”

Baltimore City State’s Attorney Stuart O. Simms, however, points out that funding for the STEP program will cover drug treatment for participants. Also, by freeing up prison space and court dockets, Simms estimates that “in one year, the cost savings of such a program will be $1.8 million.” This money can help fund an expanded treatment system.

The STEP program is modeled after the drug court in Miami, where only about one in 10 participants have been rearrested during the year following their treatment. To better the chances of the defendants’ success in beating the monkeys off their backs, the STEP program, in addition to drug treatment, provides job training, academic services, life-skills programs, job placement, and other support. It is a one-stop shop for getting your act together. All you have to do is get arrested.

Richard Farr, a cocaine addict, says people might do just that in order to get the treatment they need.

“There are a lot of people out there now who want to get into a drug program, but they can’t,” observes Farr, “so I guess you got to get caught to get into a program. It doesn’t seem right, but it sounds like that’s what you got to do.”

State’s Attorney Simms urges addicts tempted to take this route to “contact the Baltimore Substance Abuse Systems [the city’s treatment referral system] and try to see if they can get involved through the city health department. That is painstaking, that is slow, and I agree that the answer is insufficient.”

Mary Pat Clarke is more optimistic about the mayor’s AIDS Prevention Pilot Program. The $160,000 program is designed for 750 to 1,000 intravenous-drug-using participants, who will be able to exchange dirty needles for clean ones on a one-for-one basis. Another $250,000 has been dedicated for approximately 100 drug-treatment slots reserved for needle-exchange participants. Schmoke expects a needle-exchange program in Baltimore to have results similar to one in New Haven, Connecticut, where needle exchange is credited with a one-third decline in the rate of new HIV infections.

“From a public-health perspective, it is rational,” says Clarke. “Like most of us, I obviously have my concerns about the message it sends, but I think that the public-health issues are imperative. I hope that it will be successful in Baltimore City.”

Baltimore City police commissioner Tom Frazier agrees that “needle exchange is a good thing both in terms of human suffering and public-health costs.”

Clarke and Frazier are joined in support of needle exchange by many experts in the medical community. The Baltimore City Medical Society and the Medical and Chirurgical Faculty of Maryland, the city and state medical societies, respectively, are both behind the measure as a way to control the spread of AIDS without increasing drug abuse. And Dr. Michael Fingerhood, assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins and medical director of the Detox Inpatient Unit at Francis Scott Key Medical Center, says, “Most of the people in primary care who take care of people with HIV without a doubt are in favor of needle exchange.”

Dr. David Vlahov, associate professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, who has been studying the natural history HIV infection among about 600 HIV-infected IV-drug users in Baltimore since 1988, is a fervent supporter of needle exchange. Vlahov points out that there are 39 needle-exchange programs operating in the United States, that there have been numerous studies of needle exchange, including studies by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. General Accounting Office, and that the results are favorable.

“Looking across the date from a variety of different studies,” Vlahov said as he shared the Hopkins stage with Schmoke in March, “the results have been that needle-exchange programs do not encourage people to start drug use, they do not encourage current drug users to inject more frequently, they do not encourage former users to restart drug use, and they do not encourage needle sharing. So a lot of these concerns that people have had are thwarted by the data that have come forth from these studies.”

The Governor’s Executive Advisory Council, which advises and reports to Governor Schaefer on public-policy issues, just plain disagrees. Last spring it submitted a “Presentation in Opposition to Needle and Syringe Exchange Programs” to the Governor’s Drug and Alcohol Abuse Commission, the body responsible for helping to form and implement the governor’s drug-and-alcohol-abuse policies. The report concludes that the evidence on needle exchange is shaky, and “the real risk of doing real harm is too great.”

The council argues, based on what its chairman, Marshall Meyer, calls “a lot of data, research, study, and common sense,” that need-exchange programs are not safe. The list of risks include sending the wrong message about drug use, causing increased drug use and conversion to injection drugs, assisting criminal behavior, subverting drug-treatment efforts, and increasing the likelihood of “needle stick accidents.”

The council also questions whether needle exchange will work. Focusing just on needles, the report points out, overlooks the roles that other injection paraphernalia and that unsafe sex play in transmitting HIV.

“Facilitating drug use, through the provision of needles, is not likely to result in safe sexual behavior,” the report states, so it concludes that needle exchange may exacerbate the spread of sexually transmitted HIV. Finally, the council noted “that needle exchange programs are having very limited success in reaching, and even less success in keeping, the highest risk users.”

Some representatives in Baltimore’s City Council are concerned not only about mixed messages regarding condoning drug use, but also that the needle-exchange program won’t work. Councilwoman Paula Johnson Branch, of the Second District, feels that “the concept is okay, if addicts would turn the needles in and use clean needles, but I don’t think that will happen. I don’t think addicts are responsible enough to do that.”

Councilman Nick D’Adamo, of the First District, agrees: “Needle exchange is iffy to me, because if a drug user on the corner is going to shoot up, I don’t think he’ll be looking for a clean needle. I think he is going to use whatever is there at the time.”

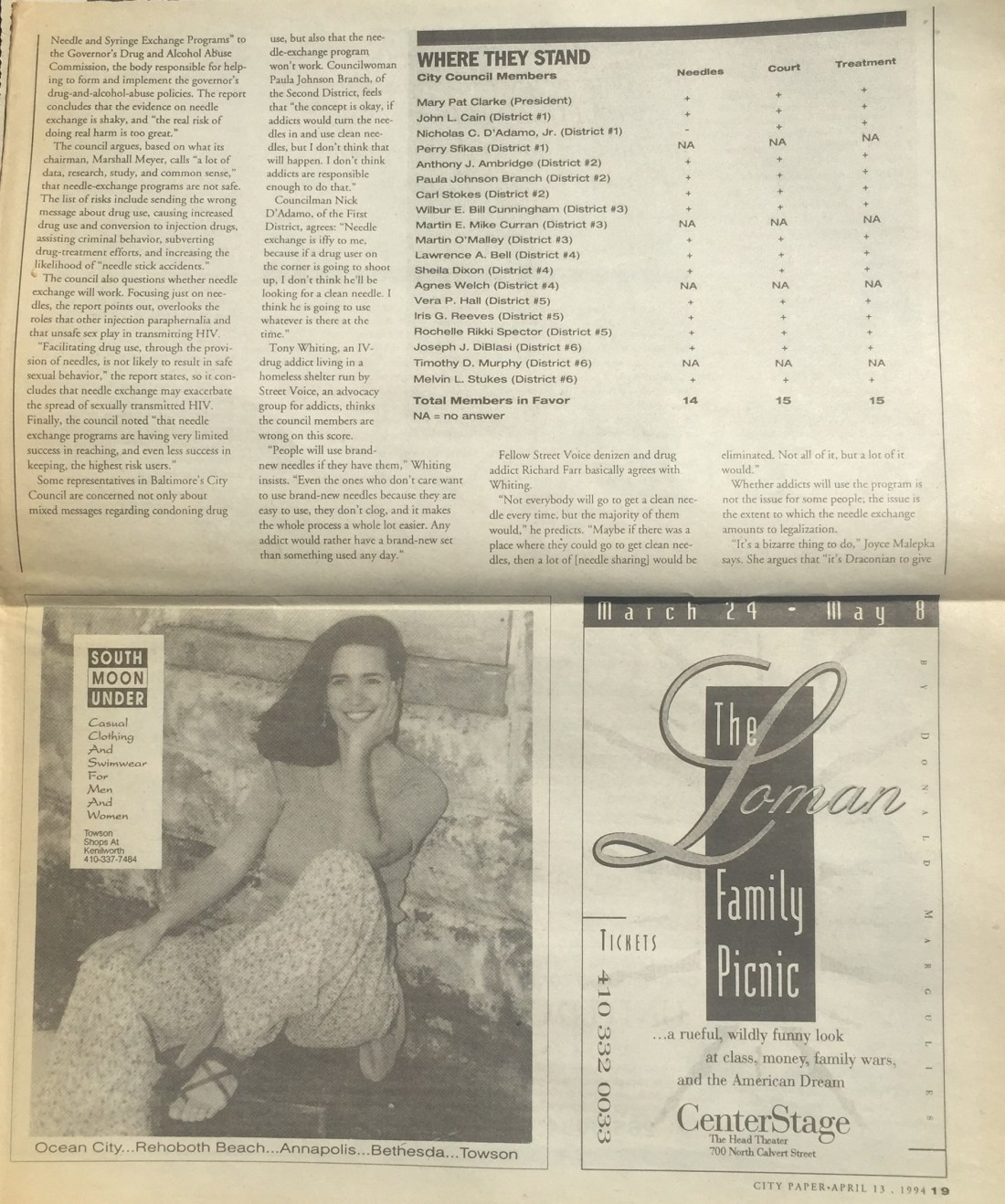

Tony Whiting, an IV-drug addict living in a homeless shelter run by Street Voice, an advocacy group for addicts, thinks the council members are wrong on this score.

“People will use brand-new needles if they have them,” Whiting insists. “Even the ones who don’t care want to use brand-new needles because they are easy to use, they don’t clog, and it makes the whole process a whole lot easier. Any addict would rather have a brand-new set than something used any day.”

Fellow Street Smart denizen and drug addict Richard Farr basically agrees with Whiting.

“Not everybody will go to get a clean needle every time, but the majority of them would,” he predicts. “Maybe if there was a place where they could go to get clean needles, then a lot of [needle sharing] would be eliminated. Not all of it, but a lot of it would.”

Whether addicts will use the program is not the issue for some people; the issue is the extent to which the needle exchange amounts to legalization.

“It’s a bizarre thing to do,” Joyce Malepka says. She argues that “it’s Draconian to give someone who injects heroin needles to continue that process. We see it as a giant step toward legalization.”

Mary Pat Clarke feels that for now, Schmoke’s visions may be delusions.

“If he can help to improve and enlarge the treatment system in Baltimore City, I would support that,” Clarke says, “but the council has been looking at the current programs and is beginning to meet with [drug treatment] providers and explore the gaps. The providers are out there, underfunded and struggling to survive and handle their caseload, and it is a system in crisis. They are overloaded, they are underfunded, and the city has failed to supply an adequate system of coordination to really assist.”

At least part of the problem is the miniscule amount of funding that comes from the city itself for drug treatment: the figure hovers around $150,000 per year, or about one percent of the total drug-treatment budget for Baltimore City. Because of this meager contribution, some people believe that Schmoke is merely canting when he calls for more treatment.

“He’s been talking like this for so many years,” Michael Gimbel says, “but how much money has he put in his budget to back up his word that he really believes in treatment? Baltimore City gets millions right now from the state for drug treatment, and the city puts virtually nothing in. Yet he wants to go to Annapolis and say, ‘My top priority is needle exchange.’ Why isn’t his top priority treatment for everybody? That is hypocrisy. That is politics, so I can’t respect that.”

Politics or not, if Schmoke manages to get 10,000 new federally funded treatment slots, it will be a coup for the beleaguered Baltimore treatment community.

According to “Baltimore’s Drug Problem,” published by the Abell Foundation, which has funded or carried out many studies about local issues for the city government, “drug treatment experts in Baltimore City suggest that the number of treatment slots needs to be increased, conservatively, by three-fold.” Since there are currently 5,300 treatment slots, Schmoke’s proposal would almost meet the target.

The mayor is seeking a meeting with Clinton Administration officials to discuss his drug-treatment proposal. In the meantime, alternative funding may be found from two other federal sources: Clinton’s crime bill, if passed by Congress, will provide more money for drug treatment, and U.S. Attorney Janet Reno has created a new block-grant program that can be used for either policing or drug treatment.

“Both of those together don’t make up ten thousand [treatment slots],” Schmoke says, “but they would allow us to almost double the number of slot that we have now.”

Despite Schmoke’s optimism, the operable word when it comes to expanded federal funding for drug treatment in Baltimore City is if. And if Schmoke doesn’t produce the proposed treatment slots, then Baltimore’s addicts will continue queuing up on the treatment waiting list and continue to rob, steal, smoke, and shoot up until they can get effective treatment for their disease. According to “Baltimore’s Drug Problem,” on any given day there are about 730 addicts on the treatment waiting list, and only one out of 10 Baltimore substances abusers who want help can get it.

Since 1988, when Schmoke opened a national debate over drug decriminalization, he has done his fair share of talking about providing the help addicts need. Now he has started to take steps to do something about it. He is determined to prove that his medicine works, and if he stays in office another term, Baltimore is destined to be the testing ground.

Schmoke, casting himself as the good doctor, has donned the white lab coat and drawn up the syringe, and Baltimore, gravely ill from the combined effects of drugs, crime, and AIDS, is rolling up its sleeve to take the dose. But will the good doctor find a vein?