By Van Smith

Published in City Paper, Aug. 5, 2009

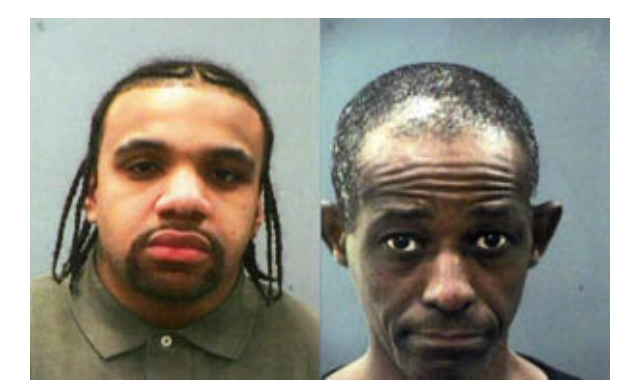

“I’m a responsible adult,” 41-year-old Avon Freeman says to Baltimore U.S. District Court Magistrate Judge James Bredar. The gold on his teeth glimmers as he speaks, his weak chin holding up a soul patch. He’s a two-time drug felon facing a new federal drug indictment, brought by a grand jury in April as part of the two conspiracy cases conducted by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in Maryland involving the Black Guerrilla Family (BGF) prison gang (“Guerrilla Warfare,” Mobtown Beat, April 22). Now it’s July 27, and Freeman, standing tall in his maroon prison jumpsuit, believes himself to be a safe bet for release. He’s being detained, pending an as-yet unscheduled trial, at downtown Baltimore’s Supermax prison facility, where he says he fears for his safety.

The particulars of Freeman’s fears are not made public, though Bredar, defense attorney Joseph Gigliotti, and Assistant U.S. Attorney Clinton Fuchs have discussed them already during an off-the-record bench conference. Danger signs from prison first cropped up in the case immediately after it was filed, though, when Fuchs’ colleague on the case, James Wallner, told a judge on Apr. 21 that the BGF had allegedly offered $10,000 for a “hit placed out on several correctional officers” and “all others involved in this investigation, and that would include prosecutors” (“BGF Offers $10,000 for Hits, Prosecutor Says,” The News Hole, April 23).

In open court, though, Gigliotti has said only that Freeman feels “endangered” by “conditions” at the Supermax, that “several of his co-defendants” also are housed there, and that “at a minimum,” Bredar should “put him in a halfway house, or at home with his sister under electronic monitoring.” The judge disagrees, but Freeman–against Judge Bredar’s adamant warning that it’s a “bad idea” and that “any statement you make could be used against you”–still wants to speak.

“I did have a job–I was working,” Freeman says of his days before his BGF arrest, and says of his family and friends, about 20 of whom are watching from the benches of the courtroom gallery, “I got the kids here, responsible adults here.” He declares he’s “not a flight risk” and says he “always come[s] to court when I’m told.” He stresses, “I am a responsible adult.”

Freeman’s doing what many people in his shoes do. He may be accused of being caught on wiretaps arranging drug transactions and of being witnessed by investigators participating in one. The prosecutor may say a raid of Freeman’s home turned up scales and $2,000 in alleged drug cash. But Freeman is still claiming to be a hard-working family man, a legitimate citizen, as safe and reliable as the next guy.

The details of the more than two dozen defendants indicted in the BGF case, filed against a Maryland offshoot of BGF’s national organization, suggest Freeman is not the only one among them who craves legitimacy. Information from court records, public documents, and the defendants’ court appearances over the past three months make some appear as “responsible adults” leading productive lives–or at least, like Freeman, as wanting to be seen that way.

Bredar sides with the government on the question of letting Freeman out of the Supermax. “There’s a high probability of conviction” based on the evidence against Freeman, Bredar says, adding that, given Freeman’s well-established criminal past, he poses a danger to society. So back Freeman goes to face his BGF fears. “I love you all,” he calls out to his 20-or-so family members and friends in the gallery, as U.S. marshals escort him out of the courtroom. “Love you, too,” some call back.

Take, for instance, Deitra Davenport. For 20 years, until her April arrest, the 37-year-old single mom worked as an administrator for a downtown Baltimore association management firm. Or 42-year-old Tyrone Dow, who with his brother has been running a car detailing shop on Lovegrove Street, behind Mount Vernon’s Belvedere Hotel, ostensibly for nearly as long. Mortgage broker and reported law student Tomeka Harris, 33, boasts of having toy drives and safe-sex events at her Belair Road bar, Club 410. Baltimore City wastewater technician Calvin Renard Robinson, 53 years old and a long-ago ex-con, owns a clothing boutique next to Hollins Market. Even 30-year-old Rainbow Lee Williams, a recently released murderer, managed to get a job working as a mentor for at-risk public-school youngsters.

The trappings of legitimacy are most elaborate, though, with Eric Marcell Brown, the lead defendant in the BGF prison-gang indictment. By the time the DEA started tapping his illegal prison cell phones in February, the 40-year-old inmate and author, who was nearing the end of a lengthy sentence for drug dealing, had teamed up with his wife, Davenport, to start a non-profit, Harambee Jamaa, which aims to promote peace and community betterment. His The Black Book: Empowering Black Families and Communities came out last year and, until the BGF indictments shut down the publishing operation, it was distributed to inmates and available to the public online from Dee Dat Publishing, a company formed by Brown and Davenport. Court documents indicate that at least 700 to 900 copies sold, at $15 or $20 a pop. The book has numerous co-authors, including Rainbow Williams.

According to the BGF case record, though, they’re all shams. Davenport, for instance, helps smuggle contraband into prison, prosecutors say, and serves as a “conduit of information” to support Brown’s violent, drug-dealing, extortion, and smuggling racket. The Black Book and Harambee Jamaa, the government’s version continues, are fronts for Brown’s ill-gotten BGF gains, which, thanks to complicit correctional employees, are derived from operating both in prisons and on the outside. As a result, the government contends, Brown appears to have had access to cigars, good liquor and Champagne, and high-end meals in his prison cell.

The alleged scheme has Dow supplying drugs to 46-year-old Kevin Glasscho, the lead defendant in the BGF drug-dealing indictment and the only one of the co-defendants who is named in both indictments. Freeman and Robinson, meanwhile, are accused of selling Glasscho’s drugs. Williams, the school mentor, is said to oversee the BGF’s street-level dealings for Brown, including violence. Harris is described as Brown’s girlfriend (even while her murder-convict husband, inmate Vernon Harris, is said by investigators to be helping Brown, too); among other things, she helps with the BGF finances. Most of the rest were inmates already, or accused drug dealers, smugglers, and armed robbers, except for the three corrections employees and one former employee who are accused as corrupt enablers, betraying public trust to help out in Brown and Glasscho’s criminal world. Only one, 59-year-old Roosevelt Drummond, accused of robbery and drug-dealing, remains at large.

Looking legit allows underworld players to insinuate themselves into the shadow economy, where the black market, lawful enterprise, and politics come together. Sometimes, though, people look legit simply because they are legit, even though they’re criminally charged. If that’s the case with any of the BGF co-defendants, they’re going to have their chance to prove it, just as the prosecutors will have theirs to prove otherwise. An adjudicated version of what happened with the BGF–be it at trial or in guilty pleas–eventually will substantiate who among them, if any, are “responsible adult[s].”

Glimpses of Brown’s leadership style are documented in the criminal evidence against him, including a conference call last Nov. 18 between Brown and two other inmates, “Comrade Doc” and Thomas Bailey, each on the line from different prisons.

“Listen, man, we [are] on the verge of big things,” Brown said, and Bailey assured him that “whatever you need me to do, man, I’m there.” “This positive movement that we are embarking upon now . . . is moving at a rapid pace,” Brown continued, and is “happening on almost every location.” He exhorted Bailey with a slogan, “Revolution is the only solution, brother,” and promised to send copies of his book, explaining how to use it as a classroom study guide.

The Black Book is a self-described “changing life styles living policy book” intended to help inmates, ex-cons, and their families navigate life successfully. Its ideological basis is rooted in the 1960s radical politics of BGF founder George Jackson, the inmate revolutionary in California who, until his death in 1971, pitched the same self-sufficient economic and social separatism that The Black Book preaches. Throughout, despite rhetorical calls for defiance against perceived oppression and injustice, it promotes what appears to be lawful behavior–with the notable exception of domestic abuse, given its instructions that the husband of a disobedient wife should “beat her lightly.”

The BGF is not mentioned by name in The Black Book, which instead refers to “The Family” (or “Jamaa,” the Swahili equivalent), explaining that it is not a “gang” but an “organization.” The back cover features printed kudos from local educators, including two-time Democratic candidate for Baltimore mayor Andrey Bundley, now a high-ranking Baltimore City public-schools official in charge of alternative-education programs. His blurb praises Brown for “not accepting the unhealthy traditions of street organizations aka gangs” and for trying “to guide his comrades toward truth, justice, freedom, and equality.”

Tyrone Powers, director of the Anne Arundel Community College’s Homeland Security and Criminal Justice Institute, and a former FBI agent, offers back-cover praise for The Black Book, describing it as an “extraordinary volume” and calling Brown and his co-authors “extraordinary insightful men and leaders.”

Powers says in a phone interview that he knows Brown “by going into the prison system as part of an effort to deal with three or four different gangs.” Powers is “totally unapologetic” about endorsing The Black Book.

“The gang problem is increasing,” Powers explains, “and we need to have direct contact with the people involved, or who have been involved. We need to be bringing the gang members together and tell them there’s no win in that, except for prison or the cemetery. Gang members can be influential in anti-gang efforts, and we have got to utilize them. Are we calling them saints? No, we are not. My objective is to reduce the violence, and I don’t think sterile academic programs work as well as engaging some of our young people, like Eric, as part of a program.”

In early May, nearly a month after Brown was indicted, Bundley explained his ties to the inmate to The Baltimore Sun. “I’ve seen [rival gangs] come together in one room and work on the lessons in The Black Book to get themselves together,” he was quoted as saying. “I know Eric Brown was a major player inside the prison doing that work. The quote on the back of the book is only about the work that I witnessed: no more, no less.”

The DEA’s original basis for tying Brown to BGF violence came from a confidential informant called “CS1” in court documents. A BGF member who’s seeking a reduced sentence, CS1 starting late last year gave a series of “debriefings” that lasted into early 2009. The investigators say in court records that CS1’s information has a track record of reliability, and the story checked out well enough to convince a grand jury to indict and a handful of judges to sign warrants as the case has progressed.

“BGF is extremely violent both inside and outside prison,” investigators recounted CS1 saying, “and is responsible for numerous crimes of violence and related crimes, including robbery, extortion, and murder for hire.” But “historically BGF has not been well-organized outside of prison,” CS1 asserted, and now the BGF “is attempting to change this within Baltimore, Maryland by becoming more organized and effective on the streets.” Brown “is coordinating and organizing BGF’s activities on the streets of Baltimore” and The Black Book “is a ploy by Brown to make BGF in Maryland appear to be a legitimate organization and not involved in criminal activity,” CS1 said, even though “Brown is a drug trafficker” and the BGF “funds its operations primarily by selling drugs.”

If CS1 is correct, then Brown is not as he was perceived by his supporters. Could it be that yet another purported peacemaker is actually prompting violence? It happened in Los Angeles last year, when a so-called “former” gangmember who headed a publicly funded non-profit called No Guns pleaded guilty to gun-running for the Mexican Mafia prison gang. It may have happened in Chicago last year, when two workers for the anti-violence group Ceasefire, which uses ex-gangmembers as street mediators, were charged in a 31-defendant gang prosecution.

Brown, with his book and his non-profit organization, wasn’t up and running at nearly the same scale as No Guns and Ceasefire, and there’s no evidence he was grant-funded. He was only just beginning to set up his self-financed positive vibe from inside his prison cell. But his is the same street-credibility pitch as in Los Angeles and Chicago: redeemed gangsters make effective gang-interventionists because the target audience will respect them more. Clearly, the approach has its risks, and Brown may end up being another example of that.

“It’s a dilemma,” Powers says of the question of how to prevent additional crimes from being committed by gang leaders who claim redemption and profess to work for reductions in gang-related violence and crime. “It has to be closely monitored.” As for Brown’s indictment, the lessons remain to be seen: “I don’t know if I can make it make sense,” Powers says.

For dramatic loss of legitimate appearances, Tomeka Harris may take the cake among the BGF co-defendants. She’s been on the ropes since late last year, when in December she caught federal bank-fraud and identity-theft charges in Maryland, in a case involving Green Dot prepaid debit cards that turned up later as the currency for the BGF’s prison-based economy. But from then until her April arrest in the BGF case, Harris had been out on conditional release–and making a good impression in public.

Media attention had been focused on Club 410, at 4509 Belair Road in Northeast Baltimore near Herring Run Park, because the police, having noted that violence was on the rise in its immediate vicinity, were trying to shut it down. At a March 26 hearing on the matter, Harris fought back, and The Sun‘s crime columnist, Peter Hermann, wrote that she “handled the case pretty well, calling into question some police accounts of the violence.” Herman described her as a “law student representing the owners,” and Sun reporter Justin Fenton, in his coverage, called her “the operator and manager” of the club. Not in the stories was the fact that she’s out on release, pending trial in a federal financial-fraud case in Baltimore.

Club 410’s liquor-board file lists as its licensees not Harris, but city employee Andrea Huff and public-schools employee Scott Brooks. Harris is referred to as its “owner” only in a March 3 police report, in which she “advised that she and her husband are the current owners of Club 410” and that “she has no dealings with the previous owners for several years.” Making matters murkier is the fact that “Andrea Huff,” whose name is on the liquor license is Harris’ alias in her BGF indictment. No wonder Sun writers were confused–Harris seems to have wanted it that way.

Harris made another public appearance before the BGF indictment came down in April. This time, it was in connection with John Zorzit, a local developer whose Nick’s Amusements, Inc., supplies “for amusement only” gaming devices to bars, taverns, restaurants, and other cash-oriented retail businesses around the region. The feds weren’t buying Zorzit’s non-gambling cover, though, and, based on a pattern of evidence that suggests he’s running a betting racket, in late January they filed a forfeiture suit and sought to seize as many of Zorzit’s assets as they could find. In the process, they raided his office on Harford Road, and there in the files were documents pertaining to Tomeka Harris and Club 410. Turns out, a Zorzit-controlled company owns Club 410, and ongoing lawsuits indicate Harris and Zorzit have had a falling out (“The 410 Factor,” Mobtown Beat, April 22).

Meanwhile, Harris still found the time to be Eric Brown’s girlfriend, according to the BGF court documents, in addition to helping the BGF smuggle, communicate, and arrange its finances. While her husband, alleged BGF member Vernon Harris (who has not been indicted in the BGF conspiracies), was in jail for murder, Tomeka Harris is said by investigators to have conducted “financial transactions involving ‘Green Dot’ cards on behalf of BGF members.” Court documents also say “one of her other business ventures was establishing bogus corporations for close associates so that they could obtain loans from banks in order to purchase high-priced items such as vehicles.”

Despite the vortex of drama that has been Harris’ life of late, she seems calm and collected at her first appearance in the BGF case on April 16. Her straight, highlighted hair hangs down the back of her black hoodie, heading south toward the tattoos peeking out from her low-hanging black hiphuggers; she’s wearing furry boots. She’s unflappable when a parole officer wonders about her claims of being a mortgage broker, when the conditions of her release in the fraud case don’t allow it.

But on June 4, a court hearing is called to try to untangle the various issues involved in Harris’ two federal indictments, and she comes undone. Her wig is gone, as are the boots and street clothes. She’s wringing her hands and holding her forehead as she talks with her lawyer, looking both exhausted and agitated. Finally, as the judge orders her detained pending trial, Harris starts crying.

The historic Belvedere Hotel has had its troubles over the years since is past glories, but it remains a highly visible symbol, like the Washington Monument, of the grandeur of Baltimore’s Mount Vernon neighborhood. Its presence in the BGF picture is a statement as to how far a prison gang’s reach may extend.

Club 410’s liquor board file contains records of 2007 drug raids carried out at Club 410 and Room 1111 at the Belvedere Hotel in Mount Vernon. The records state that evidence taken from Club 410 (a scale, razor blades, and a strainer, all with residue of suspected heroin) match evidence taken from the secure, controlled-access Belvedere Hotel condominium (a handgun, heroin residue, face masks, a heat sealer). That evidence was traced to a suspect, Michael Holman, with ties to both the Belvedere Hotel room and Club 410. Though it is unclear what, if any, ties the raids have to BGF’s currently indicted dealings, they call to mind instances in the BGF case where the Belvedere Hotel appears.

BGF court documents say Tyrone Dow, drug supplier for Kevin Glasscho’s BGF drug dealing conspiracy, “is the owner of Belvedere Detailers,” which is “located at 1014 Lovegrove Street” in Baltimore. A late-July visit there reveals that it is still operating, and that the property is right next to the rear entrance of the Belvedere Hotel parking garage.

In June 2008, Dow and his brother were highlighted in a Baltimore Examiner business article about the fortunes of Baltimore-area “garage-based premium car-wash services” during an economic downturn. Credited for Belvedere Detailers’ ongoing success is “client loyalty for the business,” which the article says Dow and his brother have operated “out of the same brick garage for more than 15 years.”

Public records of car-detailing shops operating at the Lovegrove Street location, though, don’t list Belvedere Detailers, despite the Examiner article’s claim that it’s been there for so long. In fact, no company by that name exists in Maryland’s corporate records. Instead, Mount Vernon Auto Spa LLC, headed by Hadith Demetrius Smith, has been operating there. Smith, court records show, was found guilty in Baltimore County of drug dealing in 2007, a conviction that brought additional time on a federal-drug dealing conviction from 2000, which itself violated a 1993 federal drug-dealing conviction in Washington, D.C.

City Paper‘s attempts to establish clear ties, if any exist, between Belvedere Detailers and Mount Vernon Car Wash, were unsuccessful. But the BGF investigators maintain in court records that Dow’s detailing shop at that location is tied to the prison gang’s narcotics dealings.

The Belvedere Hotel also figured in BGF investigators’ wiretap of a conversation between two BGF co-defendants, Glasscho and Darien Scipio, about a drug deal they were arranging to hold there on March 24, according to court documents.

“Yeah you gotta come down to the Belvedere Hotel, homey,” Glasscho told Scipio, who said, “Alright, I’m gonna call you when I’m close.” Just before they met there, though, Scipio called back and told Glasscho to “get the fuck away from there” because “it’s on the [police] scanner” that “the peoples is on you,” referring to law enforcers. The alleged drug deal was quickly aborted.

Glasscho, who has a 1981 murder conviction and drug-dealing and firearms convictions from the early 1990s, is accused of being the leader of a drug-trafficking operation that smuggled drugs into prison for the BGF. As the only BGF co-defendant named in both indictments, he alone bridges both the drug-dealing and the prison-gang conspiracies that the government alleges. The contention that Glasscho was a Belvedere Hotel habitu while dealing drugs for the BGF suggests that, until the indictments came down, the prison gang was becoming quite comfortable in mainstream Baltimore life.

CS1, when laying out the BGF leadership structure for DEA investigators in late 2008 and early 2009, gave special treatment to Rainbow Williams and Gregory Fitzgerald. Williams is “an extremely violent BGF member” who has “committed multiple murders” and “numerous assaults/stabbings while in prison,” CS1 contended, while Fitzgerald “has killed people in the past” and carried out “multiple stabbings on behalf of BGF while in prison.” CS1 wouldn’t actually say they were “Death Angels,” the alleged name for BGF hitmen whose identities “only certain people know,” pointing out as well that the BGF sometimes “will employ others to act as hitmen who may or may not be ‘Death Angels.'” Nonetheless, CS1 said Williams and Fitzgerald “are loyal to and take orders from” Eric Brown.

Fitzgerald was not indicted in the BGF case, and though recently released from prison on prior charges, he has since been arrested in a separate federal drug-dealing case. Williams’ fortunes, though, had been rising since he was released from prison last fall after serving out time for a murder conviction.

When Williams was named in the BGF prison-gang conspiracy, he had a job. As his lawyer, Gerald Ruter, explained in court on April 21, Williams was working for the nonprofit Partners in Progress Resource Center, a four-day-a-week gig for $1,200 a month he’d had since he left prison. Partners in Progress works with the city’s public-schools system at the Achievement Academy at Harbor City, located on Harford Road. Ruter told the judge he’d learned from Partners in Progress’ executive director, Bridget Alston-Smith (a major financial backer of Bundley’s political campaigns), that Williams “works on the campus itself as a mentor to individuals who have behavioral difficulties and is hands-on with all of the students.”

The contrast between Williams’ post-prison job, working with at-risk kids, and his alleged dealings as a top BGF leader is striking. In early April, for instance, he’s caught on the wiretap talking with Lance Walker, an alleged BGF member whose recent 40-year sentence on federal drug-dealing charges was compounded in July by a life sentence on state murder charges. Williams confides in Walker, telling him that rumors that Williams ordered the Apr. 1 stabbing murder of an inmate are putting him in danger with higher-ups in the BGF. The next day, Williams is again on the phone with an inmate, discussing how Williams is suspected of passing along Eric Brown’s order to hurt another inmate named “Coco.” Court documents also have Williams aiding in BGF’s smuggling operation and mediating beefs among BGF rivals.

And yet, Williams, with his job, was starting to appear legitimate. When law enforcers searched his apartment in April, Williams’ dedication to Brown’s cause was in evidence. Gang literature, “a large amount of mail to and from inmates,” photos of inmates and associates, and a “handwritten copy of the BGF constitution” were found, according to court documents. But they also found 38 rounds of .357 ammo. Now, Williams is back in jail, awaiting trial.

If proven right, either at trial or by guilty pleas, the accusations against the BGF in Maryland would mean not only that Brown’s legitimate-looking “movement” is a criminal sham. It would mean that the prison gang, while insinuating itself so effectively within the sprawling correctional system as to make a mockery of prison walls, was also able to embed itself in ordinary Baltimore life. If not for the indictments, should they be proved true, one can only imagine how long it could have lasted.

Calvin Robinson might have gone undetected. But the city waste-water worker, who owns real estate next to the Baltimore Police Department’s Western District station house and next to the city’s historic Hollins Market, where his In and Out Boutique clothing store continues to operate, instead was heard on the BGF wiretap talking with Glasscho about suspected drug deals. And he was observed conducting them. And when his house was raided, two guns turned up.

Robinson at least made a good show at legitimacy during court appearances in the BGF case, unlike Freeman’s performance before Judge Bredar. His lawyer played up Robinson’s city job, and even had his supervisor, Dorothy Harris, on hand in the courtroom to attest to his reliability at work. He looked poised and professional, with his clean-shaven head, trimmed mustache, and designer glasses. But just like Freeman, Robinson, who has drug convictions from the early 1990s, lost his plea to be released and was detained pending trial.

Of the 25 BGF defendants, five were granted conditional release. All of them women, they include three former prison guards, Davenport, suspected drug dealer Lakia Hatchett, and Cassandra Adams, who is Glasscho’s girlfriend and alleged accomplice. All were deemed sufficiently “responsible adults” to avoid being jailed before trial, so long as they continue to meet strict conditions. They, unlike the rest of their co-defendants, were found neither to be a threat to public safety nor a risk of flight, should they await trial outside of prison walls. Given the sprawling conspiracies, one can imagine why Freeman’s in fear at the Supermax–and why the released women should be breathing a sigh of relief.