By Van Smith

Published in City Paper, June 20, 2007

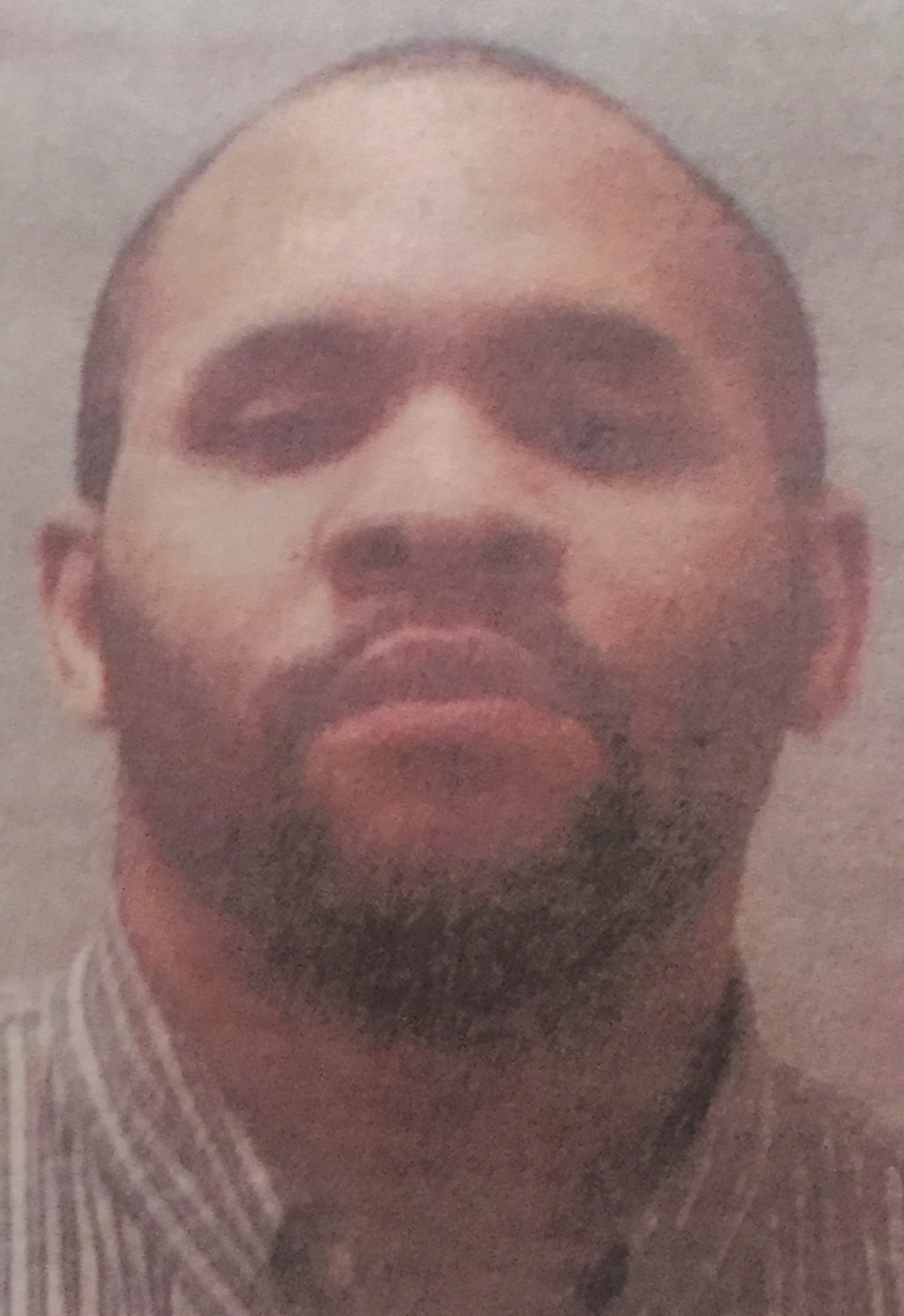

Tarsha Danielle Fitzgerald was a 34-year-oldsingle mother when she married Anthony Jerome Miller, then 27, in the spring of 2003. The two had met only recently, not long after Miller’s mother had died of cancer, and the relationship quickly grew serious. Both were congregants at West Baltimore’s New Psalmist Baptist Church in Uplands. Fitzgerald sold advertising for Magic 95.9 FM, a Radio One station, while Miller–well, Fitzgerald’s friends hardly knew anything about her fiancé, much less what he did for a living. But they knew he did a lot of nice things for her and that she was crazy about him. He fast became like a father to her two children after he moved into her Owings Mills townhouse, and they later had a child of their own. Miller even paid for the honeymoon in Mexico. He used an acquaintance’s credit card to make the final payment, claiming it was the friend’s wedding gift to the couple.

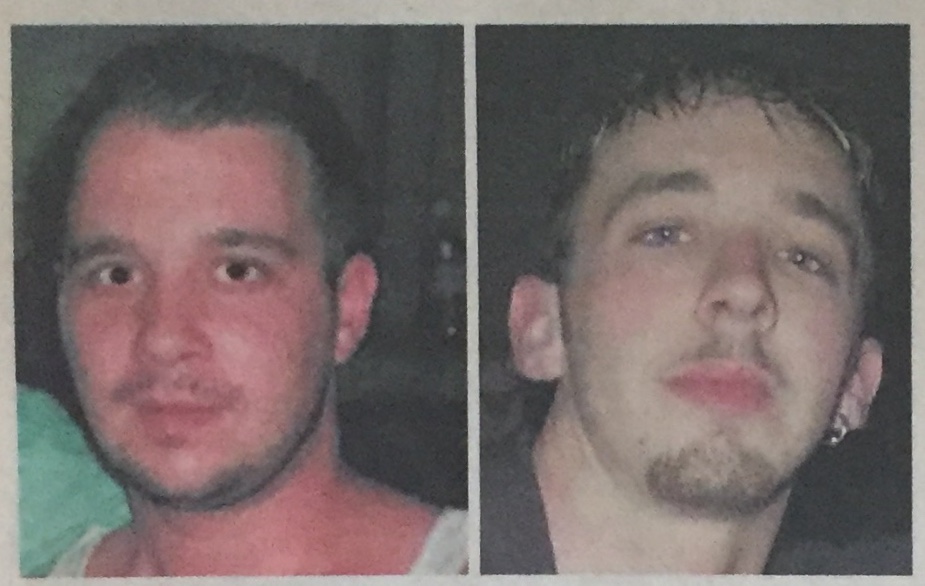

The card belonged to 31-year-old Jason Michael Convertino, the general manager of the now-defunct downtown nightclub Redwood Trust. Miller used Convertino’s card on April 12, 2003, the day after Convertino and 22-year-old Sean Michael Wisniewski, a DJ who sometimes spun vinyl at Redwood Trust, were shot to death. Nearly three years later, in January 2006, Miller was charged with the murders. In June of this year, he was sentenced to 60 years in prison. Immediately afterward, Miller appealed his conviction and filed a motion to modify the sentence.

At the time of the murders, Convertino had been arranging hip-hop celebrity appearances at Redwood Trust and was planning to take his crowd-gathering skills to another Baltimore venue, the now-defunct Bohager’s Bar and Grill. He and Wisniewski were killed on a Friday evening inside Convertino’s Gough Street rowhouse apartment, just across the street from General Wolfe Elementary School in Upper Fells Point. Their bodies were discovered five days later, after Wisniewski’s friends kicked in the door to the apartment, discovered the carnage, and called the Baltimore Police Department.

The police investigation stagnated shortly after it began, when the initial lead detective resigned from the force. That investigator, Blane Vucci, found that Miller had used Convertino’s credit card and had pawned Convertino’s laptop after the killings, but the evidence was not enough to bring charges. The investigation revived in 2005, after detective William Ritz was assigned it as a cold case and, in a matter of months, established that Miller’s DNA was found at the crime scene. Ritz, following official policy, has declined to speak on the record about the case.

Miller was on a trip with Fitzgerald in Atlanta when the murder charges were filed, and he immediately returned to Baltimore to surrender and declare his innocence. His attorney, Paul Polansky, pleaded for a speedy trial, but the proceedings were delayed when the prosecutor assigned to the case took a private-sector job and another prosecutor, Sharon Holback, took it over.

When the trial finally took place in March 2007, evidence showed that Miller and Fitzgerald both knew Convertino, whose nickname was Jay. Miller had worked briefly on Redwood Trust’s security staff, having been hired by Convertino, who knew Fitzgerald because, as a promoter, he knew who was who among the Radio One sales staff. Holback presented evidence that Miller came to Convertino’s apartment to kill him and steal his credit card and laptop in order to pay for the honeymoon, and that Wisniewski was shot dead simply because he happened to be there when Miller arrived.

On March 15, after two and a half days of deliberations, a Baltimore City Circuit Court jury found Miller guilty of two counts of second-degree murder–the non-premeditated kind–but acquitted him of handgun, robbery, and first-degree and felony murder charges. Afterward, jury members asked Judge Robert Kershaw to seal their names, so they can’t be contacted to explain their decision. The verdict seems to suggest, however, that they believed Miller killed the two, but, despite the prosecution’s evidence and arguments to the contrary, he didn’t plan to. What’s more, the jury evidently decided that he didn’t use a gun, even though that’s what killed the men, and that he didn’t rob Convertino, even though he used Convertino’s credit card and pawned his laptop. It probably wasn’t exactly what the prosecutor was hoping for, but it was a conviction.

Holback described the jury’s decision as a “compassionate verdict.” But there is room to wonder whether Miller found his way to Convertino’s apartment on his own initiative, and whether access to a stolen credit card and a laptop to hock was enough to prompt a double murder. Whether the investigation remains open is a can’t-confirm-or-deny matter, as far as law enforcement is concerned. But, despite Miller’s conviction, the Redwood Trust double murders remain mysterious.

Convertino came to Baltimore in the fall of 2002, hired to manage Redwood Trust after a couple of short gigs managing other venues in the region, including Jillian’s at Arundel Mills Mall. His résumé already boasted substantial experience managing and owning clubs in his native Binghamton, N.Y. He got his start in the business there from a club owner named Bill Uhler, who hired him in 1996 to manage a place called the Shark Club.

“He was the first to bring major DJ acts to the [Binghamton] area,” Uhler recalls in a recent phone conversation, and lists appearances by hip-hop luminaries such as Funkmaster Flex and DJ Skribble as promotions handled by Convertino. Uhler says he watched Convertino develop as an entrepreneur, both as a club owner and as an entertainment promoter, and they became close friends. By the time Convertino left for Maryland, Uhler recalls, he was a fixture in Binghamton: “Everybody in town knew him.”

Having landed at Redwood Trust, Convertino quickly consolidated the contacts necessary for successful club promotions and started his own company, J. Michaels Entertainment. He specialized in bringing in big names from the hip-hop world, who would draw throngs of paying customers happy just to be in the same venue as the featured celebrity. The star, who would have already performed elsewhere that night, would show up and hang out at the club for a while. These “after act parties” cost up-front money to arrange and carried with them the ever-present risk that the celebrity might not show or make only a fleeting appearance. In arranging these gigs, Convertino had to cross paths and make deals with a host of people in the entertainment business.

“I remember him as a wannabe promoter who was trying to be something that he’s not, and going about it in a shady fashion,” Mike Esterman recalls of Convertino. Esterman represents celebrity talent on a nonexclusive basis out of Washington but also works in the Baltimore area. “He’d say, `I’ve got $10,000 to spend on an artist,'” Esterman continues, “not telling me that he actually has $20,000, which I come to learn later. So he would try to pocket the difference. He didn’t do it to me, but I almost did deals with him that I found out about later. I come across those kinds of deals all the time, and it makes us all look bad, but he was no different than a lot of promoters.”

Baltimore-based entertainment consultant David Geller recommended that Redwood Trust owner Nicholas Argyros Piscatelli hire Convertino as the club’s manager and has a different take on Convertino’s dealings. “He was a harmless, hard-working, motivated, ambitious guy, and he was trying to be clever in a business setting,” Geller says. “Maybe Jay was networking himself to the talent, bypassing the local promoters, and it pissed somebody off. This guy, whatever his flaws were, he was just harmless. Whatever he did, he didn’t deserve to be shot.”

The idea that Convertino had angered others in the promotions business came up during Miller’s trial, when Scott Henry–owner of BuzzLife, a D.C.-based concert-promotions company, and Wisniewski’s boss–testified. Henry was one of the group of people who discovered the murder scene, and immediately afterward he was interviewed by police. During that interview, he discussed “heated arguments” that promoters had been having with Convertino. “I’d say there was maybe a deal gone bad,” he testified during Miller’s trial. Henry remains convinced there is more to the murders than Miller killing to get a credit card and a laptop. “I hope this is only the beginning, because you and I both know there is a lot more to this,” he said after his March 6 testimony.

“Jay tried to work around middlemen a lot of times,” Uhler observes. “If he met somebody through a promoter, the next time he tried to do it without [the promoter]. That may have caused problems in Baltimore. One thing I know, people with a lot of money don’t like to lose any–that’s how they ended up with a lot of money.”

Another old Binghamton friend of Convertino’s is Jason Smith, better known as DJ Boogie. Now an international artist based in New York City, he got his start doing gigs with Convertino. “Maybe Jay just went to compete against the wrong guys, and they hired somebody to kill him,” Smith says. “There are parts of Baltimore you really don’t want to mess with.”

Many tantalizing questions about Convertino’s business dealings and their possible role in his death are likely to remain unanswered–take the cash. Convertino’s body was found on his bed. Weeks later, the landlord’s cleaning crew threw the bed out into the alley to break it up and put it in a truck to haul away. When it hit the ground, a bundle of $7,900 in cash fell out of the mattress. The information about the money came out at trial, but no one testified what it was for, where he got it, whether anyone else knew about it, or how it fits into any theories about the murders. It was just a bundle of cash, stuffed in the mattress underneath Convertino’s dead body, discovered by happenstance, weeks after the crime.

During his sentencing hearing, Miller spoke publicly about the case for the first time. In the middle of his statement, his shackles jangled as he suddenly turned around to face Convertino’s mother, Pam Morgan, who was sitting about 15 feet away on a courtroom bench. Miller, an imposing, broad-shouldered man, is much bigger than the diminutive Morgan, a 55-year-old retired nutritionist from upstate New York. Over Holback’s vigorous protests and Polansky’s just-as-vigorous counterprotests, Judge Kershaw allowed Miller to continue addressing Morgan face-to-face, as well as Wisniewski’s family.

“I knew your son for a short time,” Miller said to Morgan, adding that Convertino was “a good man” and claiming that “I never had no intentions at all to hurt your son.” Miller then turned to the Wisniewskis, who, like Morgan, had come in from out of town for the sentencing, and said, “I never knew Mr. Wisniewski.” He forgave Holback for prosecuting the case, asked Kershaw for mercy, and declared, “I did none of these crimes.”

Moments later, Kershaw gave Miller the maximum sentence: 30 years for each of the two murder counts, one term to be served after the other. Under state sentencing guidelines, and barring any changes from appeals, Miller can apply for parole after serving half his prison time.

“I think justice has been served, and I’ll leave it at that,” Wisniewski’s father, Michael Wisniewski, said after Miller was led away by sheriff’s deputies. Morgan, contacted by phone the next day from her home outside of Binghamton, also said that justice was served. She has believed Miller committed the murders since shortly after they occurred, when she first learned he had used her son’s credit card to pay for his honeymoon. But Morgan, unlike Michael Wisniewski, is not prepared to leave it at that.

“I was just in shock [Miller] was even talking to me,” Morgan recalled. “I was in such awe that I don’t know if he said that he didn’t kill Jay, but the overall thing sounded like [Miller said] Jay was his good friend and that he wouldn’t have done that.”

Reminded of the exact words Miller had uttered, that he “never had no intentions at all to hurt your son,” Morgan softly said, “Oh.” She paused briefly before continuing: “Ooh, now that came out funny. That, to me, is saying that he did it, but didn’t mean to.”

Morgan recalls that, right after the murders in 2003, she was led to believe by the initial homicide investigators that the killings were done by more than one person. “From day one, they all seemed to give me the inkling that the crime scene led to at least two people being in the apartment,” she says. “I never was told any facts about how they got that. I don’t know. But that’s all they’ve all led me to believe–that, and that there was no evidence, and that they didn’t think the case would ever be solved. Up until, of course, detective Ritz took over.”

The idea that more than one person was involved in her son’s death has stuck with Morgan. Even though Miller is now serving time, she says, “I don’t know if [the truth] will come out” about the full circumstances surrounding the crime. “I hope it does, because this is the hardest thing–to live without knowing if Miller was alone, or if someone else really was the cause of Miller doing this. I really want to know the whole truth, no matter who it comes from or whatever they discover. Once I know the whole truth, I think then I’ll be OK for whatever life I have left.”

Not present at the sentencing hearing–or for most of the trial, including the verdict–was Miller’s wife, Tarsha Fitzgerald. On the fifth day of the trial, Fitzgerald arrived to assert her spousal privilege not to testify against her husband, who mouthed, “I love you,” to her as she left the courtroom without looking at him. (Fitzgerald has adamantly refused to discuss the case publicly, and has threatened to sue if her name is included in media reports about the charges against her husband.)

The son Fitzgerald and Miller had together is a toddler now and was in the courtroom for his father’s sentencing. The child was held in the arms of Miller’s brother Samuel Lester Miller III. When Holback called Anthony Miller “the ultimate sociopath” and “a cold-hearted con man,” Sam Miller stood up and left the courtroom with the baby. After the hearing, he walked down Saratoga Street outside the courthouse, still carrying Miller’s son, and declared to a reporter that “it’s not over.”

Sam Miller was reiterating a point he made at length during a phone conversation days earlier. “I hope the investigators won’t be satisfied with this,” he said of his brother’s conviction. “These murders were a conspiracy,” he continues. “Anthony might have known something about it, but sometimes people feel they have to keep their mouth shut. Do I believe he knows something? Possibly. Do I believe he’s a murderer? No. We all can be fooled, but I don’t see it in him. He’s no angel, don’t get me wrong, but I honestly just don’t see that.”

As any trial attorney who’s not in the middle of trying a case before a jury will tell you, trials aren’t really about the truth. They’re about competing interpretations of presented facts, and the jury is instructed to sort out the resulting mess. The jury’s hesitance to throw the book at Miller in its verdict may have been because of facts presented at trial that raise questions about why Convertino was murdered.

Take, for instance, the motive that Convertino’s boss may have had. Convertino was hired to manage Redwood Trust by Nicholas Piscatelli, a successful Baltimore real-estate developer. Piscatelli meticulously restored a historic downtown bank building that had survived the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904 to house his posh nightclub. Convertino, witnesses testified at Miller’s trial, was planning to take his proven skills as a scene-maker to one of Redwood Trust’s competitors, Bohager’s Bar and Grill, when the murders happened. More specifically, Convertino was scheming to take a P. Diddy event that was scheduled to happen at Redwood Trust on April 13, 2003, to Bohager’s instead; after the murders, on April 11, P. Diddy appeared at Redwood Trust, as originally planned. What’s more, Piscatelli suspected Convertino of stealing not just shows, but money from Redwood Trust.

Holback took on this nettlesome situation directly during the trial: She called Piscatelli to testify. His attorney, Peter Prevas, was present in the courtroom. Piscatelli is short and a sharp dresser–he wore a dark blue shirt and a shiny dark suit, and he hung his overcoat over the side of the witness stand as he sat down. After a few questions about his background and the Redwood Trust restoration, Holback got to the meat of the matter.

“OK,” she began, “I’m going to ask you, please, sir, to look at the jury. Did you have anything to do with the murder of Jason Convertino?”

“No, I did not,” Piscatelli responded. He didn’t so much look at the jury as quickly glance at them, and then up, down, and anywhere else but at them as he continued to answer questions. He appeared exceedingly uncomfortable but exhibited no outward outrage or anger that he was being asked if he was a murderer.

“Did you have anything to do with the murder of Sean Wisniewski?”

“No.”

“Did you have any knowledge that they were going to be murdered?”

“No.”

“Did you have any information that they might be murdered?”

“No.”

“Did you ask anyone to murder them?”

“No.”

“Did you ask anyone to murder either one of them?

“No.”

“OK. Now, do you know Anthony Miller?”

“No, I don’t.”

“Have you ever seen him?”

“No. I thought I might recognize him today, but I don’t.”

In a December 2006 interview with City Paper, however, Piscatelli recalled that Miller had asked to borrow money from him to pay for the honeymoon, but he didn’t make the loan (“Late Discovery,” Mobtown Beat, Dec. 6, 2006). While Piscatelli may not have met Miller face-to-face, he at least knew him as someone who once asked him for money.

Holback went on to ask Piscatelli about Convertino’s employment situation at Redwood Trust, about how the club was run, about the hip-hop events that Convertino was bringing in. Then she asked if he knew Tarsha Fitzgerald, and Piscatelli responded, “Sounds familiar, I don’t remember in what capacity.” Holback suddenly launched back into the hard questions:

“Did you ever ask Anthony Miller to hurt or kill Jason Convertino?”

“No.”

“Would you?”

“No, of course not.”

“Any reason to hurt him?”

“No.”

Holback went on to ask him how successful the Redwood Trust had been, and he explained that he sold the business in summer of 2003, not long after the killings. “It just wasn’t doing a lot of business,” he explained, adding that it had been a success before and during Convertino’s tenure as manager. In Piscatelli’s previous interview with City Paper, he claimed that Redwood Trust had never done well, since he’d banked on changes in the law that would have allowed it to stay open past 2 a.m., but the law wasn’t changed as he’d hoped.

Piscatelli handled Holback’s questions for 25 minutes before facing Miller’s attorney, Paul Polansky. Piscatelli described his relationship with Convertino as “good,” and added that “I liked Jason. He was a great guy. We’d go out to dinner once in a while.”

When Polansky asked whether or not Piscatelli argued with Convertino over stolen money, Piscatelli said, “I think I got upset with him when I heard that that was happening,” and testified that the argument occurred “maybe a month before” the murders. Asked when he first learned Convertino was trying to take acts to a different venue, Piscatelli said, “We just found out about that the week that he was missing, really.”

Then Polansky asked if Piscatelli had “an argument with Jason in the office in the presence of other people about the theft of the money and the fact that he was hustling business to another club?” Piscatelli responded: “You know, we were aware of it, we discussed it, we weren’t happy about it. But our feeling was, as the owners of the club, that he was bringing in money that we wouldn’t be earning, so, you know, we let it go.”

Polansky had made his point: Convertino’s skills as a nightlife manager and promoter were valuable to Redwood Trust. If Convertino went to work for a rival–Bohager’s, as he was about to do–Redwood Trust would be competing against him in the nightlife market. It might not seem like a suitable motive for murder, but neither does the theft of a credit card and a laptop. (Piscatelli has not been charged with any crime in relation to Convertino and Wisniewski’s deaths.)

Polansky had one last question for Piscatelli. Piscatelli’s answer–“No, I didn’t go to his funeral”–hung in the air as he left the courtroom.

Miller said he intended no harm, yet the victims’ bodies displayed signs of brutally intentional violence. What was found in Convertino’s apartment, after Wisniewski’s friends kicked in the door, screamed cold, calculated murder.

Wisniewski’s body was sitting in a living-room chair, his hand propping up his head. A burned-out cigarette butt lay on the floor next to him, and the television was on. He died instantly from a single bullet fired from a gun that was nearly touching the side of his head. Whoever fired the shot likely did it while coming up behind him, and Wisniewski probably never knew it was coming.

Upstairs in the bedroom, Convertino’s body lay face down on his bed. Unlike Wisniewski, he knew he was facing a violent death. The bathroom door was bashed in, evidently because Convertino had sought refuge there, though whoever killed him entered the apartment without force. He fought back, judging by his bruises. He took one bullet through his arm and another into the back of his skull, which exited through his jaw. A vase filled with pennies was broken over his head. A third bullet lodged in his cranium after being shot from close range into the back of his head. His bedding had been used to quiet the sound of the gun.

The evidence at Miller’s trial was circumstantial but strong. His skin cells were recovered from inside a latex glove found on the bedroom floor and mixed with Convertino’s blood in another piece of a latex glove that was left on the bed next to Convertino’s body. Cell-phone records put Miller near the scene at the likely time of the murders. The next day, Convertino’s credit card was used to pay for Miller’s honeymoon and purchase gasoline. A week or so before the murders, Miller’s cell phone was used to call Convertino’s immediate next-door neighbor, who testified that someone resembling Miller came to his apartment, claiming to be working for the cable company, and asked if the guy living next door made a lot of noise–ostensibly trying to determine whether gunshots might go unnoticed.

A handwriting expert who testified for the prosecution couldn’t say for certain whether Convertino’s signature on a form submitted to the travel agency authorizing Miller to use the credit card was a forgery penned by Miller, but he was pretty sure it wasn’t Convertino’s handwriting. The day after the bodies were found, Miller pawned Convertino’s Gateway laptop for $250, presenting his driver’s license to document the transaction at a Randallstown pawnshop where he was a regular customer. Two days later, he returned to the pawnshop to bring in the laptop’s power cord, which fetched another $150. How Miller ended up in possession of Convertino’s laptop was never addressed during the trial by the defense.

Polansky told the jury that if Miller did the killings, then “he’s the world’s dumbest, stupidest murderer of all time” because he left behind so much evidence for investigators. No witnesses, no recovered gun, no fingerprints, and a hugely out-of-proportion motive–robbery of a credit card and a laptop–but the trail led directly to Miller. Even his criminal record–he ducked a double-murder rap in an incident that resulted in his conviction for assault in 1993, and in 1997 he was convicted of forgery–seems to foreshadow the crime. Yet it took nearly three years for the homicides to be cleared with his arrest. And nowhere along the line did Miller act like a guilty suspect: He cut short his honeymoon to be interviewed by detectives in 2003, freely submitted his blood and handwriting exemplars in ’05, returned to Maryland to surrender immediately after the charges were filed in ’06, and steadfastly asserted his speedy-trial rights rather than delay the start of the trial.

But it’s hard to argue with DNA evidence that places Miller at the scene, wearing latex gloves. Any explanation other than that he was there, with the gloves on, when the murders were committed hasn’t been offered. Short of that, Polansky tried to convince the jury that it was a massive frame job, emphasizing how long it took to come up with the DNA evidence.

“They now say his DNA fits, years later,” Polansky argued in his opening statement at the trial. Miller “was set up for this crime,” he continued. “What would you do,” he asked the jury, if confronted with evidence “appearing that you know nothing about, and you know couldn’t have existed? I suggest that you would do exactly what Anthony Miller has done. Plead not guilty in the belief, in the prayer, that during the course of the trial the truth will emerge, and the truth will set you free.”

For a long time, Pam Morgan suspected that Nick Piscatelli had something to do with her son’s death. Her radar went up early on, when she met with detective Blane Vucci–the first lead investigator on the case–on her first visit to Baltimore, right after the murders in 2003. Morgan had thought of Piscatelli as nothing more than her son’s employer prior to the murders. But she recalls that when she told Vucci that she thought that the murders must have something to do with Redwood Trust, “because if Jay knew anybody, it would have been through the business,” Vucci’s heated reaction surprised her.

“He informed me that Nick did everything for my son, yelling at me,” Morgan says. “He told me there was no evidence, that the case would never be solved, and made it seem like somehow Jay did something wrong. And I left feeling hopeless.” (Attempts to reach Vucci for comment were unsuccessful.)

Morgan went back to upstate New York, and began to investigate the case on her own. She went through her son’s records that she had, calling any contacts she could find, and tried to share any information she developed with the Baltimore Police Department.

One of the things she shared with the police had to do with Piscatelli. About a month after the killings, in May 2003, a benefit was held near Binghamton to raise money for Convertino’s young daughter. About 500 people showed up, and while it was going on, Morgan says she was approached by a man she’d never seen before and hasn’t seen since. “He said that Nick Piscatelli was behind my son’s murder,” Morgan recalls, “that [Piscatelli had] hired someone to do it, and that he’d covered his tracks.”

Since then, Morgan had kept Piscatelli close. She says she maintained a phone relationship with him, never letting on that she suspected his involvement.

Morgan and Piscatelli spoke every few months throughout 2004 and ’05, she recalls, and more frequently in ’06 to discuss whether either of them had heard of any new developments in the case. Neither of them had. This past December, after her account of the encounter with the man at the benefit was published in City Paper after it surfaced in court papers in the Miller case (“Late Discovery,” Mobtown Beat), they spoke once more, and Morgan says she told Piscatelli that she hadn’t brought her suspicions up with him because they were based on rumor, not fact. “I never spoke with him again,” she says. (Informed of Morgan’s story about the mysterious tipster during a December 2006 interview with City Paper, Piscatelli said, “Oh boy! She said that? That’s unfortunate.”)

Morgan was not present when Piscatelli testified at Miller’s trial–it was the first and only day of the trial she missed. Now that Miller’s been convicted, she says she feels less certain about her suspicions than ever.

“If I knew Nick actually did it, if I actually had the proof” that he was somehow involved in Convertino’s death, Morgan says, “I don’t know what I would have done differently. As long as I still had a doubt and could speak to this man, I did so. So many other things are surfacing, and sometimes we are led to believe one thing when it is the opposite. Now, I have doubts that Nick is responsible. Before, I could go either way on this whole thing. But right now, it’s like I don’t know anymore.

“Don’t forget,” she continues, “[the police] told me they felt two people were involved. And of course, I’m thinking, Well, somebody came [to the benefit] and told me that. Was he the second person? Now, I don’t know.”

Or it might have been Miller, acting alone, killing two people simply to get a credit card and a laptop in order to pay for his honeymoon. If so, barring a successful appeal, Miller will be paying for that honeymoon for a long time to come.