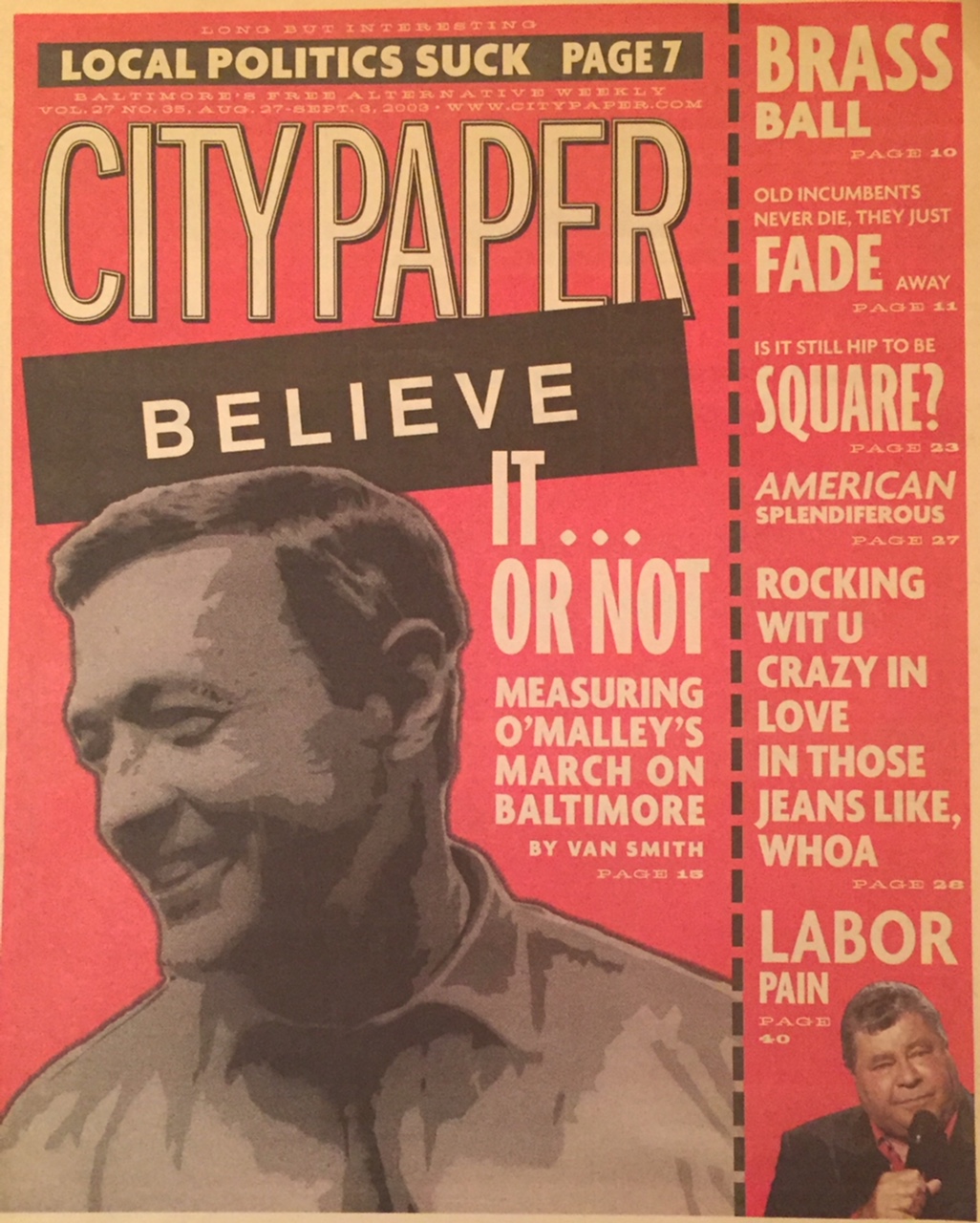

By Van Smith

Published by City Paper, Aug. 27, 2003

Good news is never hard to find when mayors seek re-election. Former Mayor Kurt Schmoke’s last political campaign in 1995 published a whole book of good news about his administration’s then-ongoing efforts in Baltimore. As is now widely recognized, though, the bad news far outweighed the good during the Schmoke years, which were marked by a cerebral approach to governance that produced paltry results and left the city’s psyche stigmatized by failure.

Schmoke’s charismatic successor, Martin O’Malley, was elected in 1999 on an ambitious anti-crime platform and a promising slogan, “For Reform and Change.” He won with a strong mandate that created high expectations and a refreshing sense of hope for the city. As he now runs for re-election as the distinct favorite in the six-way Democratic primary, O’Malley croons earnestly about the upturn Baltimore has seen during his four years in office. While his new campaign slogan–“Because Better Isn’t Good Enough”–suggests that his record has shortcomings he is willing to acknowledge, he’s still found plenty to boast about. Here’s a taste of some of the O’Malley campaign’s bragging points, lifted from its promotional materials:

- “Baltimore has, in just a few years, achieved the largest [violent-crime] reduction of any major city in America.

- “Baltimore’s per pupil spending increased by 15 percent [since 1999] . . . improving from 6th to 2nd highest in the state.

- “In 2002 alone, the Baltimore Development Corporation’s efforts brought 6,000 jobs to Baltimore.”

Also available to help boost civic optimism during this election season is the Believe campaign, a multimillion-dollar advertising effort underwritten largely by the nonprofit Baltimore Police Foundation. The campaign aims to empower Baltimoreans to overcome the ravages of illegal drugs, and its most visible impact has been the thousands of images of the word “believe” that have placarded the city since last year. Believe’s latest media blitz, which started this summer and is ongoing, charts and celebrates the city’s progress since 1999. That’s the year before O’Malley took the reins of City Hall. Thus, Believe’s current feel-good message is not only about Baltimore’s efforts to tamp down its violent drug culture but also about O’Malley’s record as mayor.

Amid this propaganda, it’s hard to know what to trust. Critical thinking, after all, demands an innate skepticism of messages in advertising, because campaigns, whether political or commercial, are designed to make use of advantageous information rather than present a balanced picture.

For instance, one could reason that Baltimore’s chart-topping reduction in violent crime is less remarkable than it sounds because, as the most violent city in the United States in 1999 (now the second most violent, behind Detroit), positive trends here have a greater statistical impact than in other, less violent cities. And while per-pupil spending increased 15 percent overall between 1999 and 2002, school enrollment during that period declined by almost 9 percent. With fewer students entering the system each year, per-student spending would increase naturally with a flat budget–and dramatically so with the modest budget increases that have been secured during O’Malley’s tenure in City Hall.

As for the 6,000 new jobs in 2002, attributed to the work of the city’s quasi-public economic development agency, that’s a lot of slots in a city where the number of unemployed people hovers around 25,000. The fact remains, though, that there were nearly 2,000 more unemployed people in the city’s labor force this June than there were in the beginning of 2002. And the unemployment rate has risen slightly rather than dropped during the same period. These facts strongly suggest that those 6,000 jobs were not filled predominantly by city residents but by commuters from surrounding areas.

Thus, the O’Malley camp’s upbeat take on the last four years begs other relevant ways to plumb Baltimore’s progress–different gauges than O’Malley’s people are emphasizing, ones that instead look at facets of city life not necessarily found in the campaign leaflets. The following results are mixed, and thus will please O’Malley supporters and detractors alike. And they show that O’Malley’s assertion that “better isn’t good enough” is dead-on in summing up his first term. The city’s stock has risen, but there’s room for improvement.

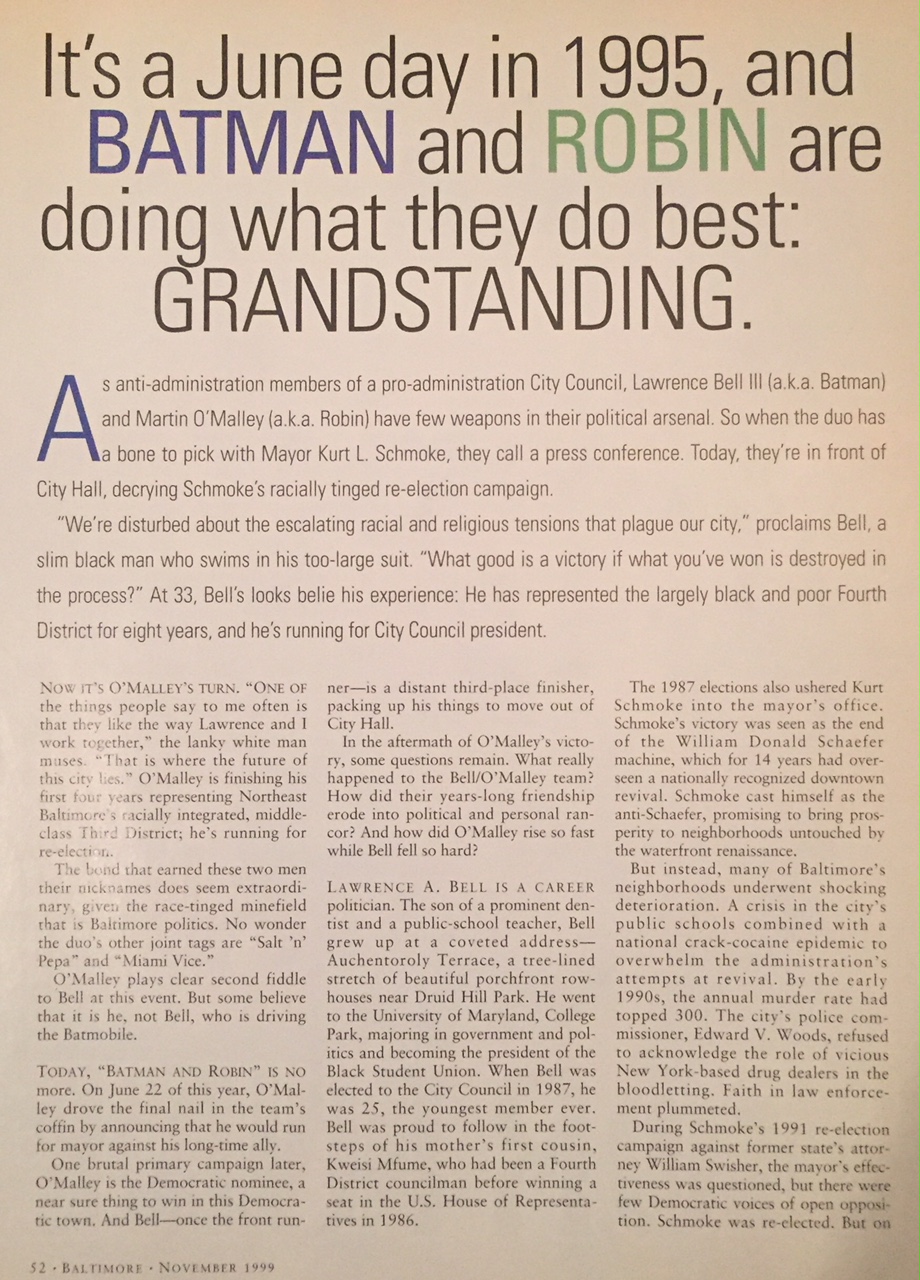

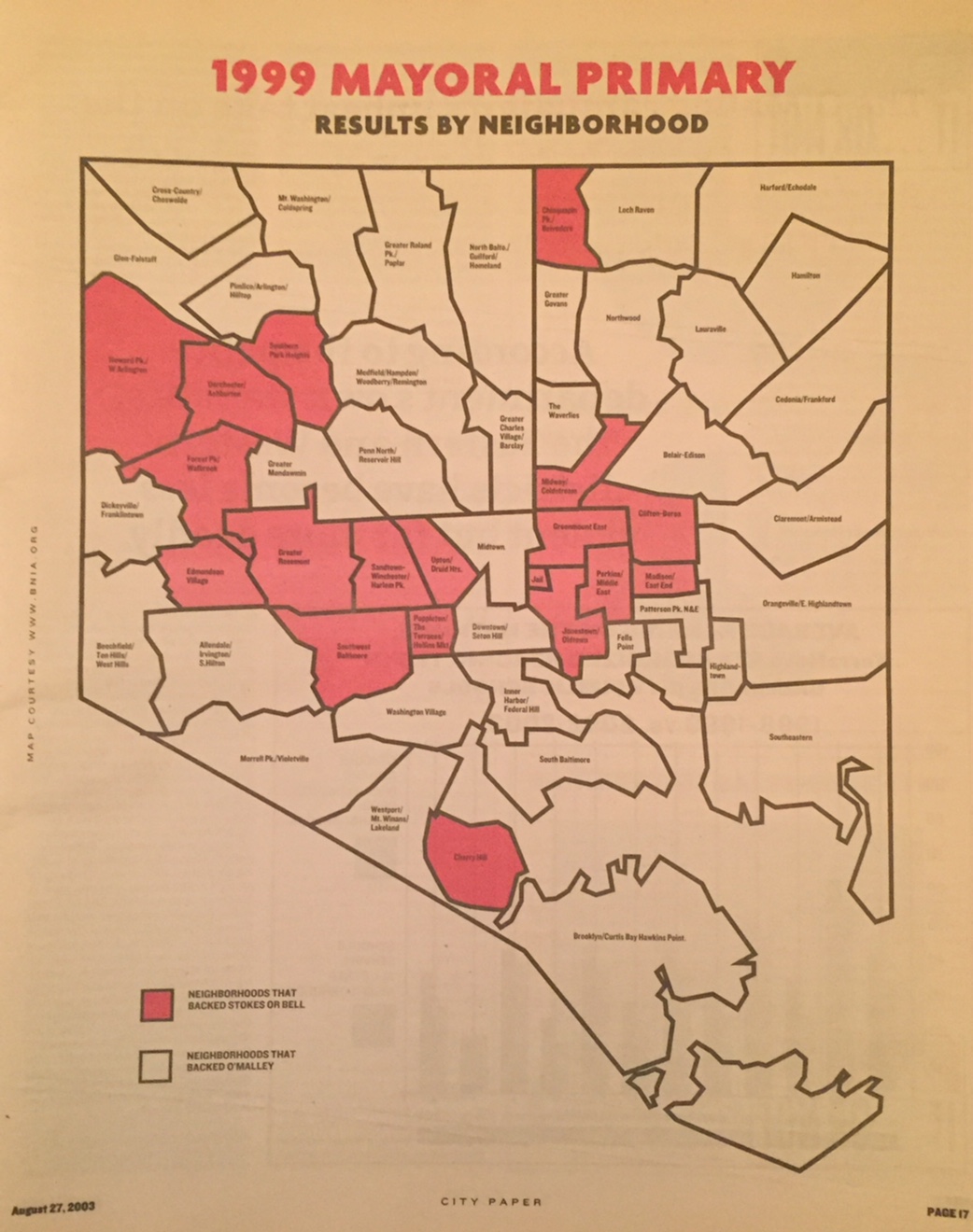

On election day 1999, Martin O’Malley was the beneficiary of a very important statistic when he chalked up 53 percent of the votes in what had shaken down to be a three-way, racially charged Democratic Primary pitting him, a white guy, against former City Councilman Carl Stokes and then-City Council President Lawrence Bell, both of whom are black. “There is more that unites us than divides us,” O’Malley often said that summer–a sentiment that, along with his bold promises to reduce crime using New York City’s successful approach as a model, resonated with an electorate that seemed exhausted from years of decline, violence, and divisiveness.

After the votes were counted, even some of those who worked against him were ebullient. “Martin O’Malley has a clear mandate from the entire city,” said former City Council president, 1995 mayoral candidate, and current 14th District City Council candidate Mary Pat Clarke, who supported Bell in the 1999 race. “This city, black and white, voted for Martin O’Malley. And it was not marginal. It was resounding. He has a mandate to lead the whole city. It’s a wondrous thing to behold.”

O’Malley’s votes in that race, nonetheless, reflected the realities of the city’s stark divide between poor African-Americans and everyone else. The precincts that supported O’Malley–including many predominantly black precincts–were spread thickly across the city, with the exception of two, hard-to-ignore areas: the blighted, poverty-stricken swaths on the east and west sides, which form a butterfly-wing pattern with midtown at the center. These neighborhoods–Upton, Druid Heights, Sandtown-Winchester, Harlem Park, Rosemont, Poppleton, Edmondson Village, and others on the west side, and Middle East, Berea, Clifton Park, Jonestown, Greenmount West, and others on the east side–did not buy into the O’Malley agenda as it was spelled out during the ’99 campaign. Stokes or Bell won most of the votes in these butterfly wings, which are overwhelmingly black and are home to about a third of the city’s population.

These neighborhoods, more than any others in the city, have the most to gain from City Hall’s policies since they suffer most from Baltimore’s famous ills. Here, according to data published by the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance (www. bnia. org), a Charles Village-based nonprofit that has taken on the Herculean task of collecting and analyzing myriad measures of Baltimore’s communities, a fifth of all serious crime is violent, vs. a 10th in the rest of the city. Here, more than a third of family households are headed by single mothers, vs. a fifth in the rest of the city. Here, about 60 percent of mothers receive first-trimester pre-natal care, vs. three-quarters of the mothers in the rest of the city. Here, nearly 40 percent of working people don’t use cars to get to their jobs, vs. less than 25 percent in the rest of the city. And here, out of every 1,000 juveniles, an average of 124 were arrested in 2001, vs. 95 in the rest of the city; the rate of juvenile arrests in these neighborhoods jumped to 142 per 1,000 juveniles in 2002. The list of disparities is long and poignant.

If, as his 1999 campaign materials noted, New York City was O’Malley’s model for success, then Baltimore’s poorest neighborhoods would benefit most from his policies, as happened during New York’s renaissance in the 1990s. Mayor Rudolph Giuliani’s approach–while widely vilified, largely because of the man’s brusque personality and a few horrific incidents involving his police force–was to commit resources where they were most needed, and thus he helped spur revival in Gotham’s most hard-pressed areas as well as its most prosperous. And, despite opinions to the contrary, Giuliani achieved these gains while reducing the number of police-involved shootings compared to his predecessor. So, has the approach worked in Baltimore under O’Malley’s guiding hand? Yes and no.

There’s just no arguing the gains made in the critical early grades of the Baltimore City public schools during the last five years. Scores in the nationwide TerraNova standardized tests rose dramatically across the board between the 1998-’99 and 2002-’03 school years in the city’s elementary-school grades. And those gains, reflected in a recently released school system report, have been greatest in schools serving the city’s poorest neighborhoods–though the situation is reversed in scores for sixth-graders. The greatest climb in average percentile rankings was in poor areas’ second-grade reading scores, which jumped an average of 23.2 points in the five-year period, while the scores rose 17.1 points for second-graders in the rest of the city’s schools. Sixth-graders scores in the poor schools, though, climbed an average of 9.6 points, compared to 19.6 at all the other city schools.

O’Malley attributes this overall success in part to expanding programs that target kids before they enter first grade. “We have gone from 109 full-day kindergarten classes to 297, reaching that mandate five years ahead of when the state wanted us to,” he cited during a recent interview with City Paper in his City Hall office. “And we’ve gone from one full-day pre-K program to 91.” He also pointed out that the school system’s efforts to standardize course content have helped, too, given that “a lot of kids are in three or four or five different schools in the course of a year, [and are faced] with a different curriculum every time.”

Kids living in poverty, O’Malley observes, have to prevail over more severe obstacles in order to learn well, so the greater improvements in test scores at schools serving poor children are that much more impressive. “The neighborhood environment from which our poor children are drawn have a lot bigger societal problems . . . [such as] violent crime, drug addiction, and the sort of societal abandonment, familial abandonment, that those things fuel, than in other areas of our city,” he said. “Unfortunately, [these students] have to overcome a lot more of the baggage that we as a society still allow to be heaped upon them through no fault of their own.

“So I don’t think it’s accidental that our kids are doing better in school as the city’s becoming safer and as more parents are getting into drug treatment,” he continued. “I think all of this works together. And the expectations for their success I think are greater than maybe they’ve been in years past.”

Of any single area under city government’s bailiwick, though, the school system is the one over which the mayor has the least direct influence. This is the result of a partial state takeover of city schools during Schmoke’s last term–a negotiated outcome to settle a long-litigated lawsuit. Thus, while O’Malley has some say over schools policy by virtue of his control over nine appointments to the 18-member school board and the city’s 23.5 percent contribution to the system’s 2002 budget, he can’t take full credit for its success or failure. Nonetheless, his limited clout in the schools arena means he can tout–with a measure of modesty–the remarkable rise in test scores as part of his record as mayor.

By and large, the city’s poorest neighborhoods fall in two of the city’s nine police districts, the Eastern and the Western. Examining the crime numbers in these two districts in 1999 and 2002, vs. the other seven districts, turns up mixed results. According to police department data, overall violent crime in the Eastern and Western districts combined has dropped 31 percent from 1999 to 2002, while nonfatal shootings have dropped almost 38 percent. But murders rose nearly 15 percent in 2002 compared to 1999–and the two districts’ share of the city’s total number of homicides has increased from nearly 30 percent in 1999 to more than 41 percent in 2002.

Running the same analysis on 2003’s year-to-date figures in the Eastern and Western districts as of Aug. 9, vs. 1999’s numbers on the same date, show that the disparity is even greater this year. Murders are up 50 percent from 1999, while violent crime has dropped more than 42 percent and shootings more than 18 percent. According to the police department’s own statistics, the Eastern and Western districts have become less violent but far more deadly.

“I had never seen these murder numbers broken down like this before,” O’Malley commented while reviewing these statistics. “It’s an interesting way to break them down.” But his response was to repeat Giuliani’s mantra: “We apply our resources to where the problems are.” And then he opened his crime-numbers notebook and recited figures showing that violent crime is down dramatically in every district, including the Eastern and Western.

“You know,” he added, “all of this is a work in progress. I’m not happy with 253.” That’s the number of murders committed citywide in 2002–a far cry from the 175 he had promised by that date during the 1999 campaign and during the first two years of his administration. “We’re going to continue to go down from there.”

And the mayor got exercised over projections of this year’s final murder tally, which as of press time is on track to reach about 285 by the end of December. “Everybody always wants to project that year-end number,” he said with palpable disgust. “I mean, they want to do it in July. And a half a year’s left. And it is awful and it’s morbid and it’s cold to talk statistics. One homicide is one homicide too many.

“But we deploy our resources to where the problems are,” O’Malley continued, getting back to the disproportionate violence in the Eastern and Western districts. “And all of this, it is still young. The open-air drug trade in this city was allowed to grow and flourish and develop and become as acute as it did over a 25-year slide. And so we are going to continue to hammer it.”

Another area that O’Malley has targeted is police corruption. It’s a ticklish subject, and one on which he mounted his bully pulpit starting in 1993, when he was a young councilman. “The few bad apples are just that–the few,” he said in an impassioned speech on the council floor 10 years ago. “But there is not a single knowledgeable person in federal, state, or local law enforcement today who will deny that we have a growing problem with street-level corruption.”

During the 1999 campaign, O’Malley repeatedly stressed the importance of “policing the police,” and continued to fuel the perception that the corruption problem in the department was acute. And he asserted that the problem had been swept under the rug for years. After he was elected, he hired a consulting firm, the Maple/Linder Group of New York City, to do a full assessment of the police department, including an internal survey of sworn officers. The findings on corruption were eye-popping. “While 48.7 percent of respondents believe that five percent or less of . . . officers are stealing money or drugs from drug dealers,” the report reads, “23.2 percent believe the number is greater than a quarter of the department.” Based on the buzz O’Malley sounded, many in Baltimore expected to see heads starting to roll.

It never really happened. There was one infamous case–Agent Brian Sewell, who was accused of planting drugs on an innocent suspect as a result of a sting operation. But the case tanked when the alleged evidence against him was pilfered by the lead investigator in the case from a secret internal-investigations office in Essex around Christmas 2000. (The department used its administrative procedures to fire Sewell. He appealed successfully, winning the right to a new trial-board hearing, but agreed to leave the force rather than go through another proceeding. Sewell recently died in an accident at Andrews Air force Base, where he had been assigned for duty with the Maryland National Guard.)

Other than Sewell, police department spokesman Matt Jablow says only three other officers–Jacqueline Folio, Scott Fullwood, and an unnamed member of the force–failed the 217 drug-related integrity stings staged by the department’s Internal Affairs Division since the beginning of 2000. The unnamed officer, Jablow explained, “struck a deal” and retired, so the department is unwilling to reveal his name.

“We’ve been doing 100 integrity stings a year for the last few years,” O’Malley explained, somewhat apologetically. “Some of them are targeted, a lot of them are random. Like everything else we do in this department, there is plenty of room for improvement as far as how we police our police. We’re doing more of it than we ever have. We have not come across that sort of beehive’s nest of every officer on a shift in a particular precinct [involved in corruption], like they had in New York, where they had a couple of celebrated cases. But [police Commissioner Kevin] Clark believes that we can do those targeted stings even more effectively than we have done them in the past.

“You don’t start a new effort like that and have it perfect overnight,” he continued. “And obviously from some of the problems that we had in some of those prosecutions [e.g., the Sewell case], it was pretty apparent that this was something new for us. But I had been somewhat surprised not to find more of that, given the way the drug trade took over big swaths of the city. But we’ll continue to be on the lookout for it and to improve the effectiveness of the investigations.”

In 1999, as O’Malley was running for mayor on an anti-crime platform, critics sometimes complained that he was a one-trick pony. Even his economic development ideas were built on crime-fighting. When asked during an interview that summer what the government’s role is in creating jobs and improving the business climate, for instance, he responded that “you do both of those things by first accomplishing job one of any organized government, which is public safety. I think there is no way to create jobs or to improve the business environment if the only businesses expanding are these open-air drug markets.”

But there was more to his plan than boosting law-enforcement. It also involved “having a mayor more actively involved with our lending institutions and letting them know where opportunities exist in this city,” he continued, “where they can make a dollar and where they can help build this city again. Businesses, their knock on city government isn’t a whole helluva lot different than citizens. Nobody returns their phone calls and nobody listens. So that’s what it’s all about.”

Today, O’Malley likes to talk about the $1.6 billion in new construction that he says is underway in Baltimore. Apparently, by that measure, his one-two punch of crime-fighting and massaging the investing class has worked pretty well. While unemployment remains high–the June figure for the city was 8.8 percent, compared to 5.2 percent for the metro region and 4.3 percent for Maryland overall–that’s largely out of his control, given the national economic recession that took hold in 2000, just as he was getting traction as the new mayor.

“We haven’t taken as severe a hit to our overall job base [during this recession] as other cities,” says Anirban Basu, an economist who heads the Fells Point-based consulting firm Optimal Solutions. “And that’s a radical departure from the recession of the early 1990s, when Baltimore was a laggard in recovering compared to other cities, which tended to come out strong during the rest of the decade. A lot of people expected a repeat performance this time, and that never materialized.” Basu attributes that in part to the wealth in the region, which means more businesses and individuals qualify to take advantage of the historically low interest rates on bank loans: “That’s why we have had such a terrific housing market in Baltimore City, which has the cheapest housing stock in the region, so it is likely people are going to look there first for deals. And many would-be renters have been empowered to buy homes.”

Baltimore’s relative prosperity amid a recession is hard to attribute directly to O’Malley’s efforts. But his efforts have certainly helped. While several formal economic-development strategies have been conceived during O’Malley’s four years in office, two were much ballyhooed early on. First, and the one that was promised often during his 1999 campaign, was to leverage the power of the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), the federal law requiring banks to make loans in poorer neighborhoods from which they draw depositors. And the second, adopted after he gained office, was to grow the local technology industry in a drive that was dubbed “The Digital Harbor.”

It’s hard to quantify how effectively O’Malley has wielded the CRA to bring new investment to Baltimore. But the extent to which he’s succeeded at all is an achievement, because the CRA has become an increasingly impotent tool in recent years. The main trend that has weakened the CRA is the fact that national mortgage-lending companies have increasingly become the lender of choice for many homebuyers and for those refinancing their mortgages. Such companies generally do not have local branches where consumers make deposits, and thus are not subject to the CRA’s provisions.

So, while O’Malley talked a big CRA game during the 1999 campaign–saying, for instance, that he would use “that hammer of monitoring the banks and the threat that you’ll mess up their business and their ability to merge and do what banks like to do in this era”–his tone has been much more conciliatory toward the banks since he took office. “A lot more of our banks were more savvy [on the CRA front] than we had anticipated,” he explained recently.

Despite the CRA’s increasingly limited reach, several local banks that do take deposits from Baltimore have outstanding CRA ratings, and they’ve stepped up to the plate with sizable CRA-eligible loans for local development efforts. Most impressive has been the Bank of America, which, by O’Malley’s tally, has financed or invested in ongoing local projects to the tune of approximately $170 million.

And O’Malley can take credit for getting banks to help underwrite the efforts of the Community Development Finance Corp., a quasi-public lending institution that makes risky loans for redevelopment in low-income areas and that was riddled with scandal under Schmoke. “Quite frankly,” he explained, “many of [the banks] were very reluctant to do it unless we put better checks and balances in place to safeguard the value of their loans. But I had several one-on-one meetings with them and lots of phone calls, lots of lobbying, begging, arm-twisting. We changed the rules at CDFC in terms of giving the banks some greater voice in the loans that we make and some greater oversight. But we got the banks to re-up, and that was to the tune of $26 million that they put into the CDFC.”

In the heady early days of his administration, Digital Harbor quickly became the most heralded piece of O’Malley’s economic-development package. “Our working waterfront,” O’Malley proclaimed in an early-2000 speech before a large gathering of the centrist Democratic Leadership Council, a national group that promotes results-oriented governance, “once again has become our port to a new economy with dozens of Digital Harbor companies filling revitalized space formerly occupied by manufacturing and warehouse equipment. We have made recruiting, supporting, and growing tech companies our highest economic-development priority because the Digital Harbor is Baltimore’s future.”

Digital Harbor was just getting up and running in 2000 when the tech-industry bubble burst. While little positive news has been heard about it since the tech collapse, local tech-industry leaders remain upbeat. “Baltimore City has done extraordinarily well” given the industry’s downturn, says Penny Lewandowski, who directs the Greater Baltimore Technology Council, a trade group based in the American Can Company complex in Canton. “I can name only three companies that did not survive–Cycle Shark, Gr8, and Tide Point LLC.” Her rosy take has required a slight shift in perspective. “Digital Harbor,” she explains, “is not just about companies that are exclusively technology, but how technology affects traditional businesses as well. So, did the mayor make the right bet? Absolutely.”

Basu gives a less optimistic appraisal of the tech industry’s status in the city today, but he backs Lewandowski’s basic conclusions. “The collapse hasn’t been quite the bloodbath it’s been nationally,” he says, pointing out that the large infusion of federal research dollars into the local economy and regional tech industry’s reliance on those federal contracts have helped. “Federal-government contracts account for about 40 percent of the state’s tech-industry revenues, versus about 10 percent in Silicon Valley.”

The main reason for tech’s resilience in Baltimore in the face of a national downturn, Basu says, is that Baltimore had less to lose than other cities. “Baltimore has not been a hotbed of private-sector technology in much of its history,” he explains. “It was late in coming to the table–and then, just as the momentum was building, the tech industry goes bust.”

O’Malley’s focus in the tech arena also has shifted since the tech collapse–from information technology and telecommunications, which were the hardest hit areas, to biotechnology, which is a less mercurial beast. “What we are trying to do,” he explained, “is to create the expectation that in our already fairly diverse economy, that we are ready and have the natural resources–the colleges and universities and research institutions–to be able to grow that sector of the economy which could be called the new economy. And I think our area, where we have greater strengths than others, is going to be in biotech.” To that end, the city is soon to become home to two biotechnology parks–one on the east side and affiliated with Johns Hopkins University; the other on the west side, being developed by the University of Maryland.

City government’s role in all of this is not so much “the bricks-and-mortar visibility,” O’Malley said, but work-force development–investing in programs that will prepare city residents to participate in the new economy. And he’s more than happy, along with his technology coordinator, Mario Armstrong, to recite a list of new initiatives. First and foremost, O’Malley and Armstrong explain, is the radical gain in the ratio of students to computers in the classroom. “We used to be at 10 to 1, now we’re at three-and-a-half to one,” Armstrong said enthusiastically. “That was us making it a priority,” O’Malley continues, “Carmen [Russo, the outgoing city schools chief] not fighting us on being involved in it, a million dollars of general funds, and 6,000 computers from the Social Security Administration, which we paid to have retrofitted.”

Armstrong’s list of other programs and accomplishments is long and sounds impressive. The Hewlett-Packard Digital Village program aims to train teachers to use computers and incorporate them into class curriculum so students learn in a tech-savvy environment. Digital Village Hubs, which are after-school centers that provide public access to computers, have been established at three locations on the east side. Many of the city’s public-housing projects now have computer centers, and about 1,200 people a month are using them. Five computer-oriented Youth Opportunity Centers have been opened around the city, giving children more occasions to use computers after school. And three Digital Learning Labs have opened, which provide computer-training courses that, in June, taught almost 500 people how to use the technology.

Whether all of this activity actually results in a more job-ready work force for the city’s still-fledgling new economy is the question. As Basu says of the city’s work force-development initiatives, “it will be interesting to see how well it works, but it’s good to see they’re trying.”

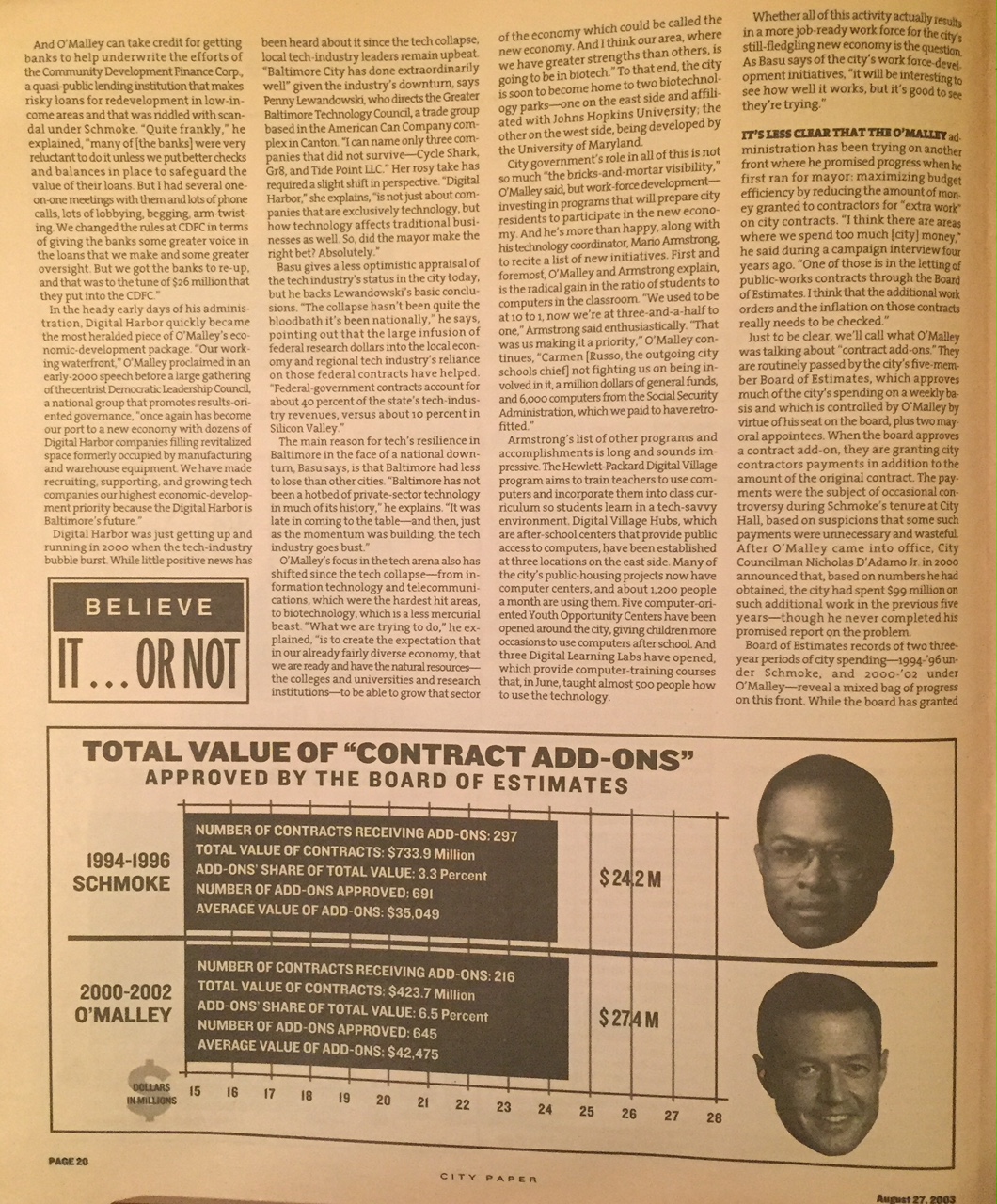

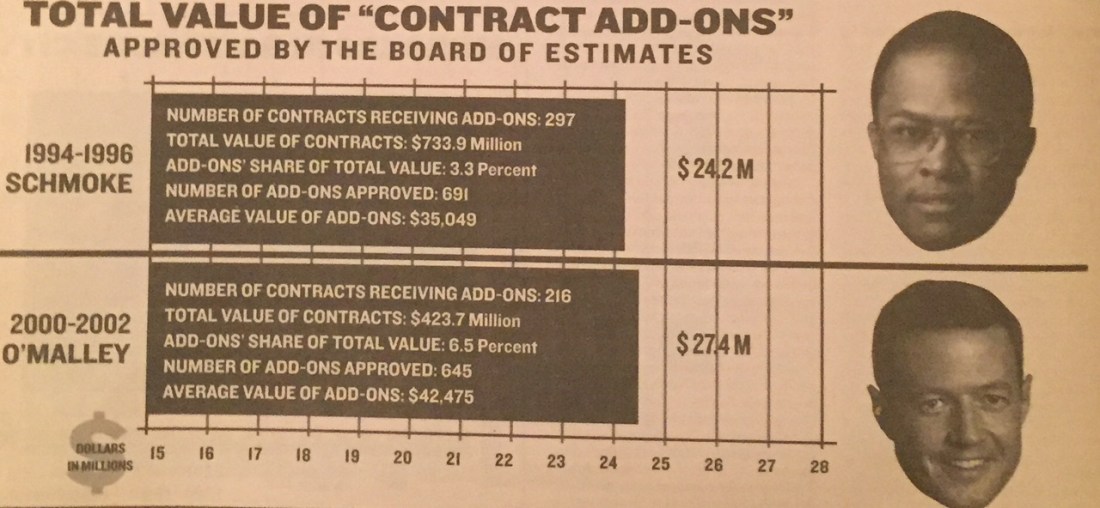

It’s less clear that the O’malley administration has been trying on another front where he promised progress when he first ran for mayor: maximizing budget efficiency by reducing the amount of money granted to contractors for “extra work” on city contracts. “I think there are areas where we spend too much [city] money,” he said during a campaign interview four years ago. “One of those is in the letting of public-works contracts through the Board of Estimates. I think that the additional work orders and the inflation on those contracts really needs to be checked.”

Just to be clear, we’ll call what O’Malley was talking about “contract add-ons.” They are routinely passed by the city’s five-member Board of Estimates, which approves much of the city’s spending on a weekly basis and which is controlled by O’Malley by virtue of his seat on the board, plus two mayoral appointees. When the board approves a contract add-on, they are granting city contractors payments in addition to the amount of the original contract. The payments were the subject of occasional controversy during Schmoke’s tenure at City Hall, based on suspicions that some such payments were unnecessary and wasteful. After O’Malley came into office, City Councilman Nicholas D’Adamo Jr. in 2000 announced that, based on numbers he had obtained, the city had spent $99 million on such additional work in the previous five years–though he never completed his promised report on the problem.

Board of Estimates records of two three-year periods of city spending–1994-’96 under Schmoke, and 2000-’02 under O’Malley–reveal a mixed bag of progress on this front. While the board has granted fewer add-ons under O’Malley than they did under Schmoke and has reduced the number of contracts receiving additional work, the amounts granted have grown–especially when measured as a share of the total value of city contracts receiving additional payments. While the city spent $24.2 million on add-ons during the three-year period under Schmoke, it spent $27.4 million on such additional payments under O’Malley–and the add-ons’ share of the total value of contracts rose from 3.3 percent to 6.5 percent.

The mayor’s office provided alternative figures to City Paper, but they don’t square with the records of the Board of Estimates, which were the basis for City Paper‘s analysis and which are the only source available for the public to independently research city spending patterns. Raquel Guillory, the mayor’s chief spokeswoman, told City Paper the total value of contracts from 1994 through ’96 was $323,649,981, with add-ons comprising 8.4 percent of that total, while the figures for 2000 through ’02 were $379,340,369 and 7.2 percent, respectively. Thus, the O’Malley administration’s numbers show efficiency–add-ons as a percentage of total contract amounts–has increased under O’Malley, while City Paper shows greatly increased inefficiency under O’Malley.

City Paper asked Guillory to explain how city government arrived at their figures. She said that the city’s numbers were derived from the sum total of construction contracts that came before the Board of Estimates for contract add-ons. City Paper based its figures on the sum total of all city contracts–including everything from waste-water treatment improvements to consulting work to digital mapping of the city.

Guillory also explains that two projects worked on under the O’Malley administration–extensive and glitch-riddled contracts on the police headquarters building and Hopkins Plaza downtown–were held over from the Schmoke administration and made up for a large amount of the extra work passed by the Board of Estimates during O’Malley’s term. Also, O’Malley adds, city managers have “been trying to do a better job in terms of the degree of detail that’s in the contracts to begin with, when they go out for bid,” explaining that “if we put out better contracts, we might get the job done for less, without these expensive overages.” So far, the Board of Estimate records don’t reflect the improvements O’Malley suggested have had a money-saving effect, because both the amount and the share of additional work have risen markedly compared to the Schmoke administration in the mid-1990s.

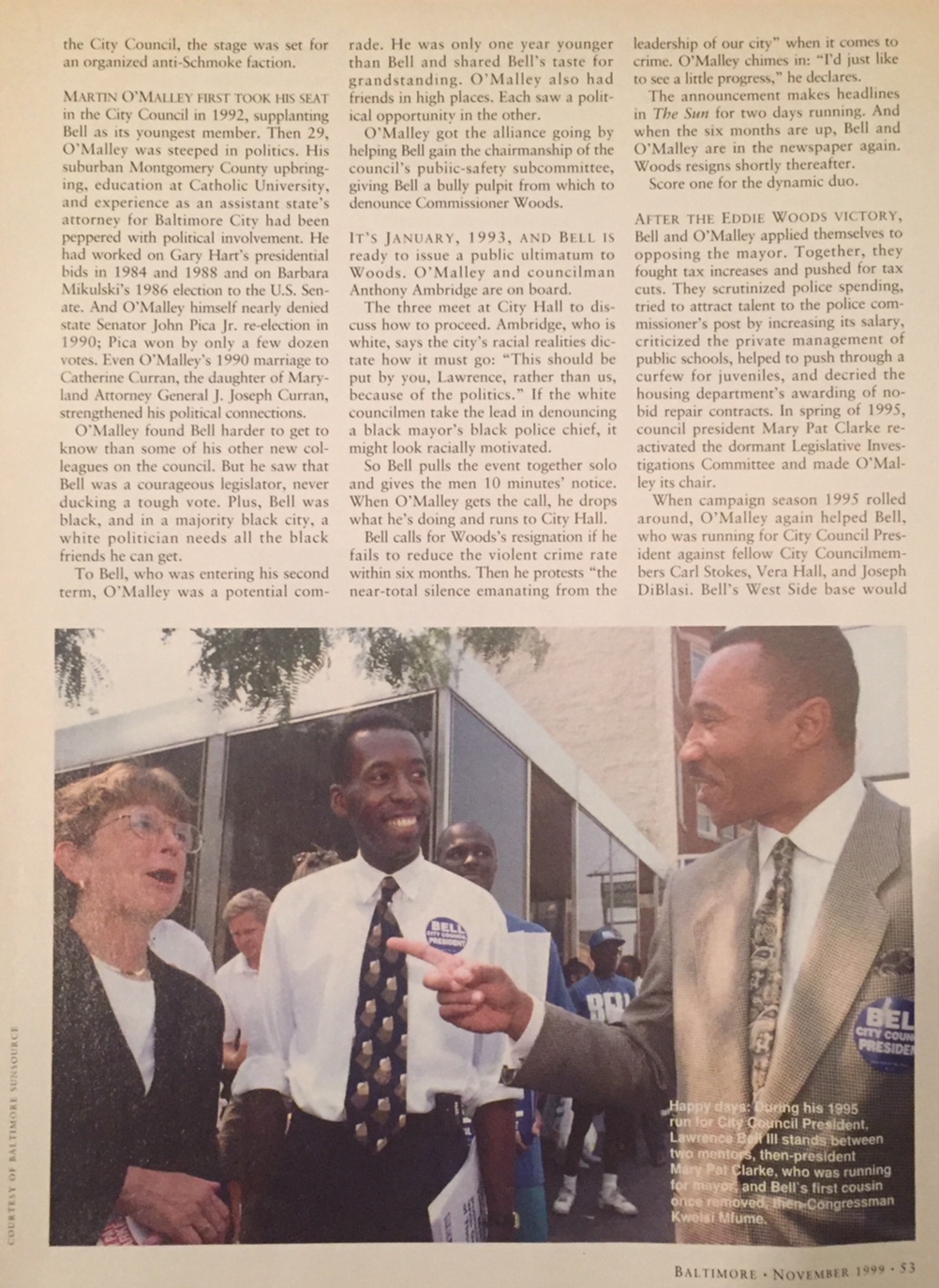

In the heady days after winning the 1999 primary, O’Malley sat down with a reporter to discuss his victory. One of the many interesting facets of the story was the demise of the once-famous friendship between O’Malley and his longtime partner in politics, Lawrence Bell, whom he trounced at the ballot boxes. Bell, O’Malley believed, had messed up his electoral fortunes with a variety of missteps, but primarily by ditching his long-established political persona as an independent rebel and choosing instead to align himself with the established political forces behind Schmoke.

“I said,” O’Malley recalled in 1999, “‘Even if you are lucky enough to stumble into this thing backwards, you are not going to be able to usher in the sort of change the city needs by relying on the old warhorses. It won’t be possible.’ I said, ‘How you win also dictates how you are able to govern.’ I said, ‘If you win this way, you won’t be able to govern.'”

O’Malley’s 1999 mayoral campaign, in contrast to Bell’s, was marked by efficient fund-raising and spending, a hard-working and diverse cadre of workers, a focus on a few key issues, backing from a panoply of state leaders, and support from an energized public. Like Bell, though, he relied on old warhorses–even older than Bell’s. Not Schmoke’s people (though many of them have since come into the O’Malley fold), but those of his father-in-law, state Attorney General Joseph Curran Jr., and those of State Comptroller (and former mayor and governor) William Donald Schaefer, whose long-loyal cronies turned up in thick numbers in O’Malley’s 1999 campaign and have been well represented in O’Malley’s brain trust. Among them are lawyer-advisor Richard Berndt and former deputy mayor Laurie Schwartz, who left O’Malley’s cabinet last winter after serving since he was elected.

If O’Malley’s advice to Bell was accurate–that “how you win also dictates how you are able to govern”–then O’Malley’s admirably well-run 1999 campaign would lead to overall good governance with fundamental reform limited by his reliance on “old warhorses.” Either way, O’Malley now sums up his first four years in office with the half-apologetic campaign slogan “Because Better Isn’t Good Enough.” And now it’s up to the voters to decide whether–given his record of improved school-test scores, more deadly violence in poor neighborhoods, limited success fighting police corruption, greater private investment and work-force development efforts, and inefficient city contracts–better was in fact good enough. We’ll find out when the votes are tallied.