By Van Smith

Published in City Paper, May 8, 1996

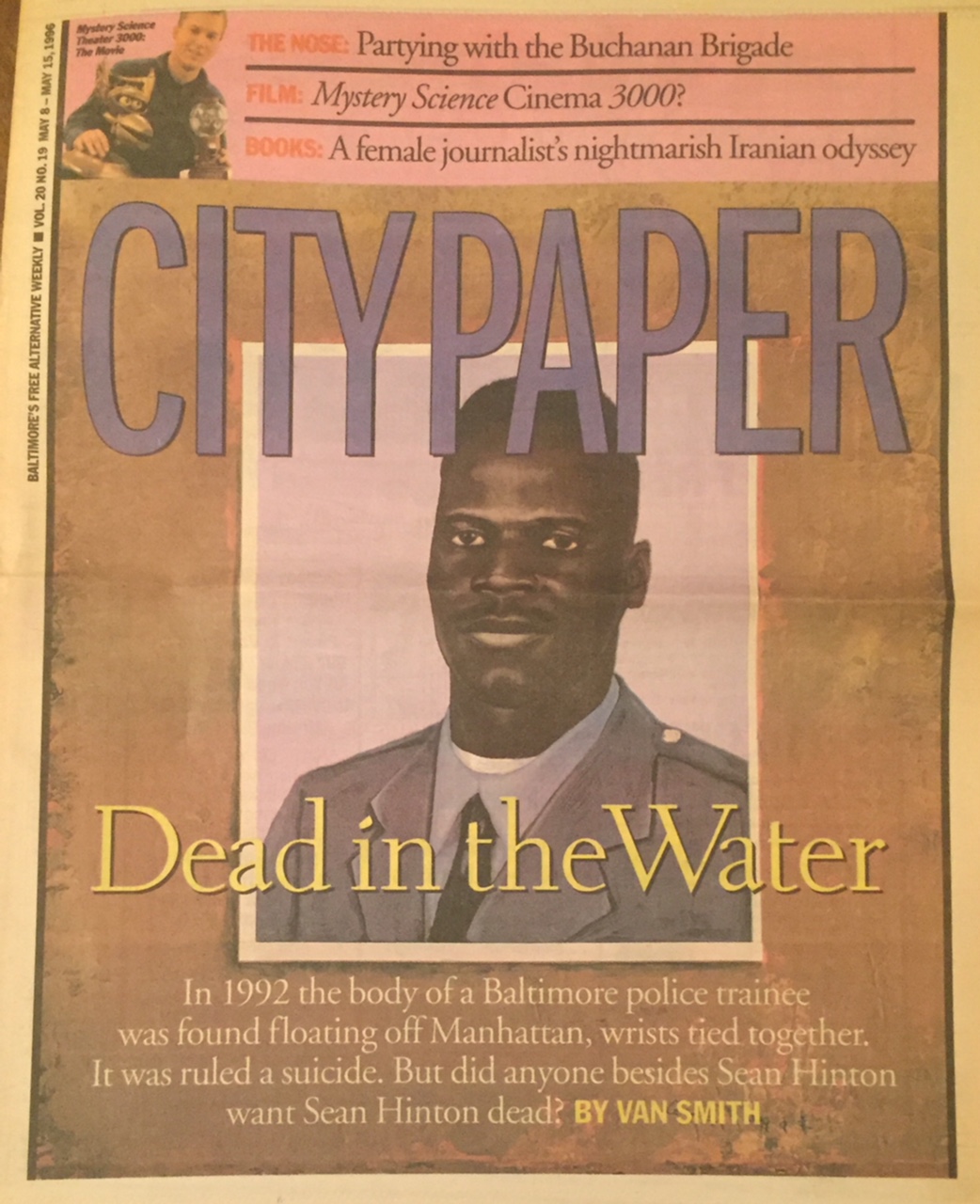

A 22-year-old Baltimore police trainee, married with three children and living in a public-housing apartment, has a career-shattering week that includes being arrested for drunken-driving and being accused of involvement in police corruption. He disappears after leaving a cryptic good-bye note to his wife.

Ten days later, he turns up dead in New York, floating facedown in the water off the southern tip of Manhattan. No one knows how he got there. His wrists are tied together in front of him. Initial reports filed by New York officials who recovered the body describe head trauma and a possible bullet hole in his cheek, but the autopsy report notes no signs of injury or a struggle. Three weeks later, a New York medical examiner rules the case a suicide by drowning.

The Sean Hinton case is a tantalizing riddle with very few clues. The Baltimore City Police Department (BCPD) recently released Hinton’s personnel file, which includes the results of a questionable-death investigation. BCPD’s Internal Investigations Division (IID) conducted probes and there may have been other Baltimore-based investigations as well, but the results haven’t been released. The New York Police Department (NYPD) won’t comment, saying the case is still under investigation. Hinton’s family wants answers. But a limited number of documents and other pieces of evidence, and the recollections of a few reliable sources, are all they have to go on.

Considering the clues that are available, there are only two plausible explanations for Hinton’s death: suicide or homicide. It is possible to reconstruct, blow by blow, the verifiable events that led the medical examiner to conclude – with some speculation – that it was a suicide. It is also possible to find oversights and misinterpretations – at least one of which bears strongly on the suicide ruling – in the autopsy report.

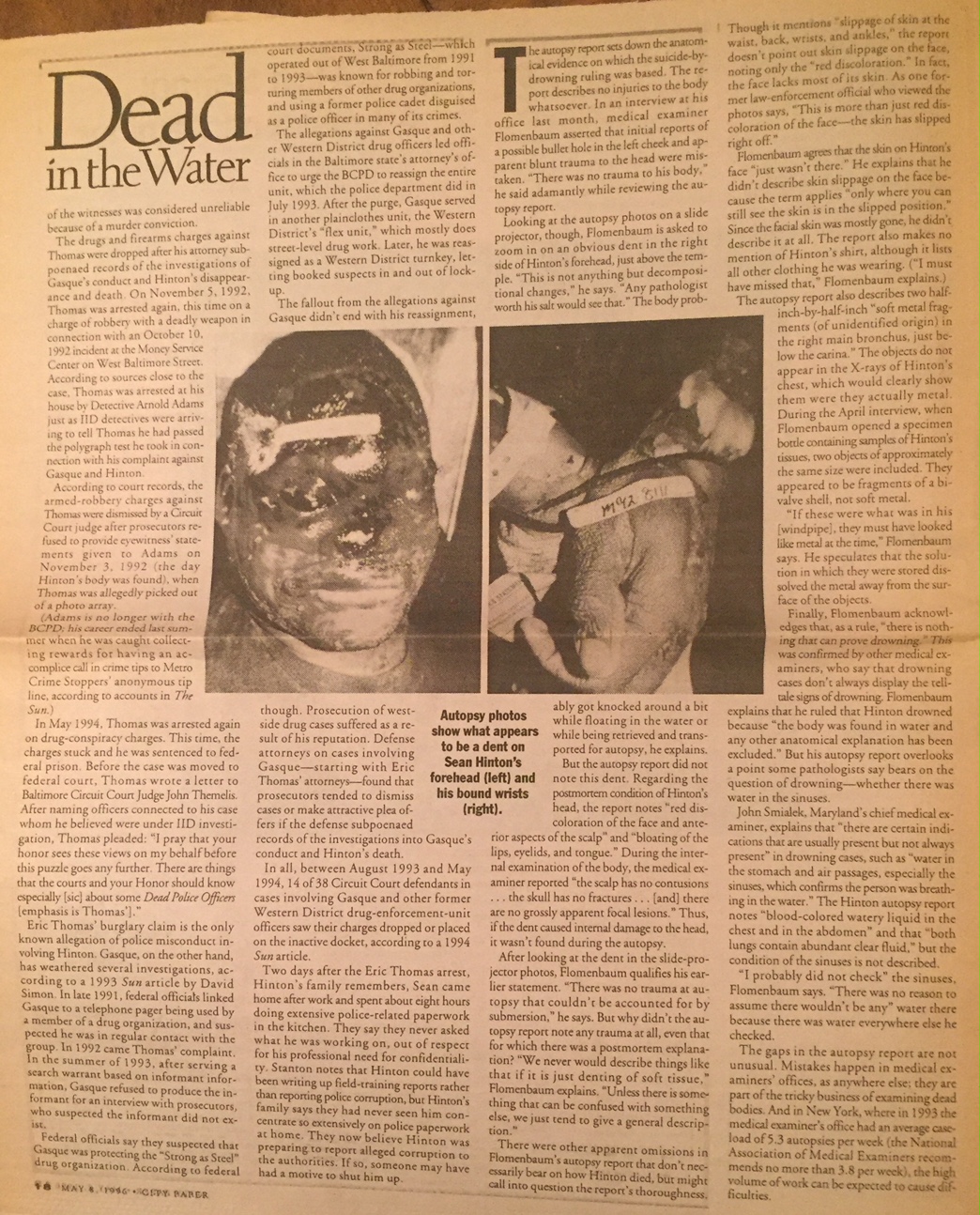

Autopsy photos show an obvious dent above Hinton’s right temple. Today, the medical examiner says the injury occurred after death. But he did not describe it in his autopsy report three-and-a-half years ago, even though the head trauma was noted when the body was pulled out of the water. This oversight leaves open the question of whether the dent occurred before or after Hinton’s death – a question that is vital to determining whether or not Hinton killed himself.

Judgment calls are a necessary part of a medical examiner’s work; not every death can be explained based only on the physical evidence and the known circumstances. But not all deaths have a possible murder motive, either. Hinton’s did. And the medical examiner didn’t know about it when he ruled on Hinton’s death.

Two nights before Sean Hinton disappeared, his family recalls, he spent about eight hours at home preparing extensive police paperwork. Two days before that, he had made a drug bust with BCPD Officer Stanley Gasque, whose career has been marked by complaints of alleged corruption, according to published news accounts and court records. After the arrest, the suspect filed a complaint with IID alleging that Gasque, Hinton, and another officer burglarized his house. Within a year of this incident, the eight members of the Western District drug-enforcement unit to which Gasque belonged had been reassigned, although no criminal charges were ever filed against them. Hinton’s family now believes that Sean knew something and was planning to report it.

BCPD Lieutenant Robert Stanton, who worked on the Hinton case for the homicide department, says his investigation ended after the suicide ruling, a week after he started. His December 10, 1992 report on the case concludes: “It is obvious that a number of questions concerning this incident will long linger and possibly remain unanswered. The fact that the body is found out of jurisdiction and never viewed by anyone from this agency puts us at a disadvantage from the start.”

Stanton says he “wasn’t made privy to most of” the IID investigations of Hinton’s death and the alleged burglary. “IID is a separate entity,” he explains, adding, “I didn’t find anything that made the connection” between his investigation and theirs. Once the death was ruled a suicide, Stanton’s investigation was closed.

Had the manner of death been listed as “undetermined,” Stanton would have pursued the questionable-death investigation further. Perhaps he would have turned up more clues or discovered the possible murder motive; the case for ruling the death either a suicide or a homicide might have been bolstered. As it is, based on what little information has been made available to them, Hinton’s family is convinced Sean was murdered and the truth covered up.

It is Saturday, October 24, 1992. Hinton returns to his Lafayette Courts apartment after getting his car out of impoundment. The young police trainee is due to graduate from the academy in a few weeks, but his fledgling career is suddenly a shambles.

A drug suspect Hinton helped bust on Tuesday the 20th has filed a complaint alleging that Hinton and two officers burglarized his house after the arrest. The night of Friday the 23rd, Hinton had been arrested on drunken-driving charges. Saturday morning, still in the police lockup, he called his friend, 67-year-old Forrest Lee Moore – the man Hinton called “Granddaddy” – and said he expected to have to beg to remain with the police department. (In fact, three days after Sean disappeared, he was fired for misconduct, according to documents in his personnel file.)

Back at home, Hinton opens a spiral notebook and writes a letter to his wife, which she finds eight days later. “24 Oct 92, 540 pm time written. Francine you have dealt with me 4 years, and you never seemed to believe I really loved you – I do love you. You have Jehovah on your side. I have no one. I need Jehovah but I just can’t seem to reach him. So I guess I’ll see someone. Please take care of our children for me. 1744 hrs. Sean Hinton.”

Then he walks out of the apartment and heads toward Orleans Street, leaving his car behind. About an hour later, he calls home to say he’ll be right back. When he fails to show, his mother, Jean Hinton, consults her caller-ID system and discovers he had called from Pennsylvania Station at 6:48 P.M. Shortly after midnight, the Hintons report Sean missing.

Ten days later, on Tuesday, November 3 – the same day Bill Clinton is elected president – Hinton turns up dead. His body is found floating facedown in the water behind New York’s Batter Park Coast Guard Station, the wrists tied up in front with the drawstring of his jacket. His wallet contains $42.95 and several pieces of identification, including a Fraternal Order of Police membership card.

It is around 10:30 A.M. when the body is taken out of the water. An investigator from the New York Medical Examiner’s Office arrives at the scene. He writes in his report, “Decedent is an app. homicide victim. Hands are bound, and head trauma noted.” Several New York police officers also are present on the dock. One files a report at 10:55, noting the body is a “Poss. homicide, hands tied together with black cord and poss. bullet hole left cheek.” When the body is transported to the medical examiner’s office, it is labeled with a tag that reads HOMICIDE.

Five hours later in Baltimore, Joseph Kleinota, BCPD missing-persons detective, who up until then had no breaks in the Hinton case, reports that he has spoken to New York homicide detective Joseph Burdick. His report documents Burdick as saying that a “preliminary investigation reveals that subject committed suicide. … It appears that the person had tied his own hands.”

Burdick also files a report of the conversation. He writes that Kleinota told him Hinton had left a note and that he “had recently become despondent over an arrest and a dept. Disciplinary hearing he was due to attend regarding this arrest.”

The next day, November 4, New York medical examiner Mark Flomenbaum conducts the autopsy. Given the level of decomposition, he figures Hinton has been dead for several days at least. He notes fluid in Hinton’s chest, abdomen, and lungs, indicating drowning as the cause of death. Examining the bound wrists, he jots on his autopsy work sheet: “Comment: appears to req. great deal of facility to do by self.” He describes “soft metal fragments” lodged in the victim’s windpipe. Other than the effects of decomposition, Flomenbaum notes nothing else remarkable about the body.

After the autopsy, Flomenbaum decides the case is a possible suicide. But he isn’t sure yet, so he files a death certificate stating the cause as drowning and leaving the manner of death open, “pending further studies.” On November 27, convinced after consultation with various New York and Baltimore investigators that Hinton intended to and was capable of tying his own wrists to hinder his ability to swim, Flomenbaum changes his ruling to suicide by drowning.

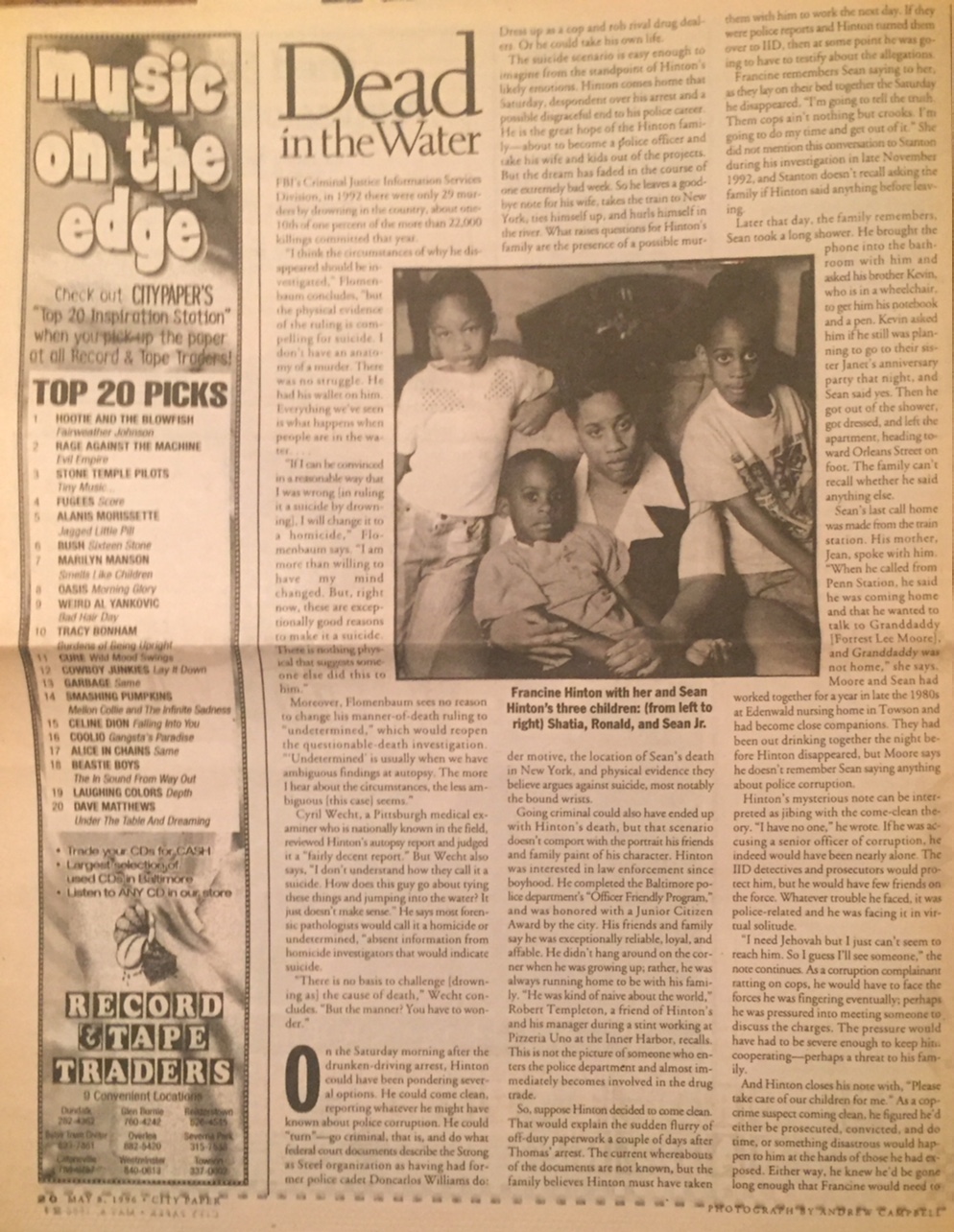

In a nutshell, that is the story of Sean Hinton’s demise. According to Francine Hinton, the police department expressed its sympathy by covering the funeral costs, paying out insurance money, and outfitting their children – Ronald, Sean, Jr., and Shatia, then one, three, and five years old – with some new clothes.

She isn’t satisfied with the explanation that Sean committed suicide, though. Neither are his mother, sisters, brothers, and friends.

That is to be expected; authorities say family members and friends almost always respond to suicide with disbelief. But Sean Hinton’s case is not like most suicides. First, there is a possible motive for murder.

On October 20, 1992, Hinton was working with Gasque, who had returned several months before to the Western District drug-enforcement unit after being moved to patrol because federal officials suspected he was connected to a drug ring, according to a 1993 Sun article. Why a police trainee was working with this particular officer is unknown, but it is a question the family would very much like to have answered.

After receiving information from a confidential informant, Gasque and Hinton arrested Eric Thomas on drugs and firearms charges in a school zone in West Baltimore. Shortly after the arrest, Thomas complained to IID that Gasque, Hinton, and another, unnamed cop confiscated his keys while booking him and went to his house and stole property, including money. A Baltimore City grand jury heard testimony from several witnesses who said they saw the burglary, but no indictment was handed down. BCPD Lieutenant Stanton explains that one of the witnesses was considered unreliable because of a murder conviction.

The drugs and firearms charges against Thomas were dropped after his attorney subpoenaed records of the investigations of Gasque’s conduct and Hinton’s disappearance and death. On November 5, 1992, Thomas was arrested again, this time on a charge of robbery with a deadly weapon in connection with an October 10, 1992 incident at the Money Service Center on West Baltimore Street. According to sources close to the case, Thomas was arrested at his house by Detective Arnold Adams just as IID detectives were arriving to tell Thomas he had passed the polygraph test he took in connection with his complaint against Gasque and Hinton.

According to court records, the armed-robbery charges against Thomas were dismissed by a Circuit Court judge after prosecutors refused to provide eyewitness’ statements given to Adams on November 3, 1992 (the day Hinton’s body was found), when Thomas was allegedly picked out of a photo array.

(Adams is no longer with the BCPD; his career ended last summer when he was caught collecting rewards for having an accomplice call in crime tips to Metro Crime Stoppers’ anonymous tip line, according to accounts in The Sun.)

In May 1994, Thomas was arrested again on drug-conspiracy charges. This time, the charges stuck and he was sentenced to federal prison. Before the case was moved to federal court, Thomas wrote a letter to Baltimore Circuit Court Judge John Themelis. After naming officers connected to his case whom he believed were under IID investigation, Thomas pleaded: “I pray that your honor sees these views on my behalf before this puzzle goes any further. There are things that the courts and your Honor should know especially [sic] about some Dead Police Officers [emphasis is Thomas’].”

Eric Thomas’ burglary claim is the only known allegation of police misconduct involving Hinton. Gasque, on the other hand, has weathered several investigations, according to a 1993 Sun article by David Simon. In late 1991, federal officials linked Gasque to a telephone pager being used by a member of a drug organization, and suspected he was in regular contact with the group. In 1992 came Thomas’ complaint. In the summer of 1993, after serving a search warrant based on informant information, Gasque refused to produce the informant for an interview with prosecutors, who suspected the informant did not exist.

Federal officials say they suspected that Gasque was protecting the “Strong as Steel” drug organization. According to federal court documents, Strong as Steel – which operated out of West Baltimore from 1991 to 1993 – was known for robbing and torturing members of other drug organization, and using a former police cadet disguised as a police officer in many of its crimes.

The allegations against Gasque and other Western District drug officers led officials in the Baltimore state’s attorney’s office to urge the BCPD to reassign the entire unit, which the police department did in July 1993. After the purge, Gasque served in another plainclothes unit, the Western District’s “flex unit,” which mostly does street-level drug work. Later, he was reassigned as a Western District turnkey, letting booked suspects in and out of lockup.

The fallout from the allegations against Gasque didn’t end with his reassignment, though. Prosecution of westside drug cases suffered as a result of his reputation. Defense attorneys on cases involving Gasque – staring with Eric Thomas’ attorneys – found that prosecutors tended to dismiss cases or make attractive plea offers if the defense subpoenaed records of the investigations into Gasque’s conduct and Hinton’s death.

In all, between August 1993 and May 1994, 14 of 38 Circuit Court defendants in cases involving Gasque and other former Western District drug-enforcement-unit officers saw their charges dropped or placed on the inactive docket, according to a 1994 Sun article.

Two days after the Eric Thomas arrest, Hinton’s family remembers, Sean came home after work and spent about eight hours doing extensive police-related paperwork in the kitchen. They say they never asked what he was working on, out of respect for his professional need for confidentiality. Stanton notes that Hinton could have been writing up field-training reports rather than reporting police corruption, but Hinton’s family says they had never seen him concentrate so extensively on police paperwork at home. They now believe Hinton was preparing to report alleged corruption to the authorities. If so, someone may have had a motive to shut him up.

The autopsy report sets down the anatomical evidence on which the suicide-by-drowning ruling was based. The report describes no injuries to the body whatsoever. In an interview at his office last month, medical examiner Flomenbaum asserted that initial reports of a possible bullet hole in the left cheek and apparent blunt trauma to the head were mistaken. “There was no trauma to his body,” he said adamantly while reviewing the autopsy report.

Looking at the autopsy photos on a slide project, though, Flomenbaum is asked to zoom in on an obvious dent in the right side of Hinton’s forehead, just above the temple. “This is not anything but decompositional changes,” he says. “Any pathologist worth his salt would see that.” The body probably got knocked around a bit while floating in the water or while being retrieved and transported for autopsy, he says.

But the autopsy report did not note this dent. Regarding the postmortem condition of Hinton’s head, the report notes “red discoloration of the face and anterior aspects of the scalp” and “bloating of the lips, eyelids, and tongue.” During the internal examination of the body, the medical examiner reported “the scalp has no contusions … the skull has no fractures … [and] there are no grossly apparent focal lesions.” Thus, if the dent caused internal damage to the head, it wasn’t found during the autopsy.

After looking at the dent in the slide-projector photos, Flomenbaum qualifies his earlier statement. “There was no trauma at autopsy that couldn’t be accounted for by submersion,” he says. But why didn’t the autopsy report note any trauma at all, even that for which there was a postmortem explanation? “We never would describe things like that if it is just denting of soft tissue,” Flomenbaum explains. “Unless there is something that can be confused with something else, we just tend to give a general description.”

There were other apparent omissions in Flomenbaum’s autopsy report that don’t necessarily bear on how Hinton died, but might call into question the report’s thoroughness. Though it mentions “slippage of the skin at the waist, back, wrists, and ankles,” the report doesn’t point out skin slippage on the face, noting only the “red discoloration.” In fact, the face lacks most of its skin. As one former law-enforcement official who viewed the photos says, “This is more than just red discoloration of the face – the skin has slipped right off.”

Flomenbaum agrees that the skin on Hinton’s face “just wasn’t there.” He explains that he didn’t describe skin slippage on the face because the term applies only where you can still see the skin is in the slipped position.” Since the facial skin was mostly gone, he didn’t describe it at all. The report also makes no mention of Hinton’s shirt, although it lists all other clothing he was wearing. (“I must have missed that,” Flomenbaum explains.)

The autopsy report also describes two half-inch-by-half-inch “soft metal fragments (of unidentified origin) in the right main bronchus, just below the carina.” The objects do not appear in the X-rays of Hinton’s chest, which would clearly show them were they actually metal. During the April interview, when Flomenbaum opened a specimen bottle containing samples of Hinton’s tissues, two objects of approximately the same size were included. They appeared to be fragments of a bivalve shell, not soft metal.

“If these were what was in his [windpipe], they must have looked like metal at the time,” Flomenbaum says. He speculates that the solution in which they were stored dissolved the metal away from the surface of the objects.

Finally, Flomenbaum acknowledges that, as a rule, “there is nothing that can prove drowning.” This was confirmed by other medical examiners, who say that drowning cases don’t always display the tell-tale signs of drowning. Flomenbaum explains that he ruled that Hinton drowned because “the body was found in the water and any other anatomical explanation has been excluded.” But his autopsy report overlooks a point some pathologists say bears on the question of drowning – whether there was water in the sinuses.

John Smialek, Maryland’s chief medical examiner, explains that “there are certain indications that are usually present but not always present” in drowning cases, such as “water in the stomach and air passages, especially the sinuses, which confirms the person was breathing in the water.” The Hinton autopsy report notes “blood-colored watery liquid in the chest and in the abdomen” and that “both lungs contain abundant clear fluid,” but the condition of the sinuses is not described.

The gaps in the autopsy report are not unusual. Mistakes happen in medical examiners’ offices, as anywhere else; they are part of the tricky business of examining dead bodies. And in New York, where in 1993 the medical examiner’s office had an average caseload of 5.3 autopsies per week (the National Association of Medical Examiners recommends no more than 3.8 per week), the high volume of work can be expected to cause difficulties.

Due to possible oversights, corpses are sometimes exhumed for second autopsies which can reveal previously overlooked details that help solve mysteries. In a celebrated early-1980s case, for instance, an Illinois coroner missed three skull fractures on the head of a woman named Karla Brown. The fractures were discovered after Brown’s body was exhumed four years later, a step that led to a murder conviction.

In addition to a possible murder motive and the questionable autopsy, the Hinton case is curious because of the manner and cause of his death. Only one or two percent of all suicides are by drowning, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

And there is the larger question of Hinton’s bound wrists. Flomenbaum, looking at slides of Hinton’s wrists, concludes, “This is not somebody trying to immobilize him. It is a simple knot that is possible to do by yourself.” He says reliable sources involved in investigating the case informed him that Hinton could have done it himself. And he dismisses as naivete his comment in his initial autopsy notes that the knot would require a “great deal of facility to do by self.” The autopsy report says the wrists were tied together with a square knot, a knot that seems impossible to use in binding one’s own hands. (This reporter tried several times and could not do it in a way that would adequately bind the wrists.) Perhaps Hinton tied the knot, then twisted his wrists up tight into the knotted drawstring. Either way, if Hinton bound himself it took considerable dexterity and effort.

When Flomenbaum ruled the case a suicide on November 27, 1992, he was not aware of the allegations of corruption surrounding Hinton. The first he heard of them was in March 1996, when a reporter called him to discuss the case. At the time of the ruling, he said during the April interview, all he knew was that Hinton disappeared after being charged with drunken driving and after leaving a note for his wife. “People kill themselves for a lot less than DWIs,” he says.

Flomenbaum describes Hinton’s note as “very weird. … There’s no mention that he’s going to kill himself.” But he says he still believes it “very strongly supports suicide.” And the new information about Hinton’s circumstances at the time he died, Flomenbaum believes, only bolsters his initial ruling.

“It looks like he was probably involved with some big-time, major shit,” Flomenbaum says. “He saw no way out. He probably wanted to do something right, but was so trapped, it seemed [suicide] was his only option.”

Besides, Flomenbaum continues, “if someone did have a motive to kill him, how did they do it? This is not a homicidal drowning. Homicidal drownings are very, very rare.” He’s right; they are even more rare than suicideal drownings. According to the FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services Division, in 1992 there were only 29 murders by drowning in the country, about one-10th of one percent of the more than 22,000 killings committed that year.

“I think the circumstances of why he disappeared should be investigated,” Flomenbaum concludes, “but the physical evidence of the ruling is compelling for suicide. I don’t have an anatomy of a murder. There was no struggle. He had his wallet on him. Everything we’ve seen is what happens when people are in the water. …

“If I can be convinced in a reasonable way that I was wrong [in ruling it a suicide by drowning], I will change it to a homicide,” Flomenbaum says. “I am more than willing to have my mind changed. But, right now, these are exceptionally good reasons to make it a suicide. There is nothing physical that suggests someone else did this to him.”

Moreover, Flomenbaum sees no reason to change his manner-of-death ruling to “undetermined,” which would reopen the questionable-death investigation. “’Undetermined’ is usually when we have ambiguous findings at autopsy. The more I hear about the circumstances, the less ambiguous [this case] seems.”

Cyril Wecht, a Pittsburgh medical examiner who is nationally known in the field, reviewed Hinton’s autopsy report and judged it a “fairly decent report.” But Wecht also says, “I don’t understand how they call it a suicide. How does this guy go about tying these things and jumping in the water? It just doesn’t make sense.” He says most forensic pathologists would call it a homicide or undetermined, “absent information from homicide investigators that would indicate suicide.

“There is no basis to challenge [drowning as] the cause of death,” Wecht concludes. “But the manner? You have to wonder.”

On the Saturday morning after the drunken-driving arrest, Hinton could have been pondering several options. He could come clean, reporting whatever he might have known about police corruption. He could “turn” – go criminal, that is, and do what federal court documents describe the Strong as Steel organization as having had former police cadet Doncarlos Williams do: Dress up as a cop and rob rival drug dealers. Or he could take his own life.

The suicide scenario is easy enough to imagine from the standpoint of Hinton’s likely emotions. Hinton comes home that Saturday, despondent over his arrest and a possible disgraceful end to his police career. He is the great hope of the Hinton family – about to become a police officer and take his wife and kids out of the projects. But the dream has faded in the course of one extremely bad week. So he leaves a good-bye note for his wife, takes the train to New York, ties himself up, and hurls himself in the river. What raises questions for Hinton’s family are the presence of a possible murder motive, the location of Sean’s death in New York, and physical evidence they believe argues against suicide, most notably the bound wrists.

Going criminal could also have ended up with Hinton’s death, but that scenario doesn’t comport with the portrait his friends and family paint of his character. Hinton was interested in law enforcement since boyhood. He completed the Baltimore police department’s “Officer Friendly Program” and was honored with a Junior Citizen Award by the city. His friends and family say he was exceptionally reliable, loyal, and affable. He didn’t hang around on the corner when he was growing up; rather, he was always running home to be with his family. “He was kind of naïve about the world,” Robert Templeton, a friend of Hinton’s and his manager during a stint working at Pizzeria Uno at the Inner Harbor, recalls. This is not the picture of someone who enters the police department and almost immediately becomes involved in the drug trade.

So, suppose Hinton decided to come clean. That would explain the sudden flurry of off-duty paperwork a couple of days after Thomas’ arrest. The current whereabouts of the documents are not known, but the family believes Hinton must have taken them with him to work the next day. If they were police reports and Hinton turned them over to IID, then at some point he was going to have to testify about the allegations.

Francine remembers Sean saying to her, as they lay on their bed together the Saturday he disappeared, “I’m going to tell the truth. Them cops ain’t nothing but crooks. I’m going to do my time and get out of it.” She did not mention this conversation to Stanton during his investigation in late November 1992, and Stanton doesn’t recall asking the family if Hinton said anything before leaving.

Later that day, the family remembers, Sean took a long shower. He brought the phone into the bathroom with him and asked his brother Kevin, who is in a wheelchair, to get him his notebook and a pen. Kevin asked him if he still was planning to go to their sister Janet’s anniversary party that night, and Sean said yes. Then he got out of the shower, got dressed, and left the apartment, heading toward Orleans Street on foot. The family can’t recall if he said anything else.

Sean’s last call home was made from the train station. His mother, Jean, spoke with him. “When he called from Penn Station, he said he was coming home and that he wanted to talk to Granddaddy [Forrest Lee Moore], and Granddaddy was not home,” she says. Moore and Sean had worked together for a year in the late 1980s at Edenwald nursing home in Towson and had become close companions. They had been out drinking together the night before Hinton disappeared, but Moore says he doesn’t remember Sean saying anything about police corruption.

Hinton’s mysterious note can be interpreted as jibing with the come-clean theory. “I have no one,” he wrote. If was accusing a senior officer of corruption, he indeed would have been nearly alone. The IID detectives and prosecutors would protect him, but he would have few friends on the force. Whatever trouble he faced, it was police-related and he was facing it in virtual solitude.

“I need Jehovah but I just can’t seem to find him. So I guess I’ll see someone,” the note continues. As a corruption complainant ratting on cops, he would have to face the forces he was fingering eventually; perhaps he was pressured into meeting someone to discuss the charges. The pressure would have had to be severe enough to keep him cooperating – perhaps a threat to his family.

And Hinton closes his note with, “Please take care of our children for me.” As a cop-crime suspect coming clean, he figured he’d either be prosecuted, convicted, and do time, or something disastrous would happen to him at the hands of those he had exposed. Either way, he knew he’d be gone long enough that Francine would need to care for the children alone.

So Hinton went to Penn Station. No one knows what happened to him between his call home at 6:48 P.M. that Saturday and when his body was taken out of the water in New York 10 days later. It seems likely he took the train to New York, but he had no ticket stub when he was found. He did not have a credit card, and the family’s and investigators’ accounts differ on how much money Hinton had when he left home. (Francine disputes that he had enough to buy a $59 one-way ticket to New York.)

If the come-clean interpretation of the good-bye note is correct and he did meet with someone connected to corruption allegations, perhaps he was forced to accompany the person or person to New York and was told everything would be fine for everyone if he cooperated.

The killer or killers would have reasoned that, in Baltimore, a drowned 22-year-old city-police trainee would attract a lot of attention and a lot of press – and police here might quickly discern a possible murder motive. If he dies in New York, the case would probably get a lot less notice – and, with a waterlogged body and a wallet full of identification, it might look like a suicide.

The murder scenario continues like this: Arriving in New York, the party – with Hinton still cooperating – disembarks from the train without incident and heads for a desolate stretch of Manhattan waterfront. Hinton is knocked in the temple and falls unconscious without a struggle. The killers bind his wrists to make sure he can’t swim, throw him in the water, and walk away.

The come-clean scenario stand or falls with the question of when the trauma to Hinton’s head occurred. Did it happen before or after he drowned? And while the autopsy report says the skull isn’t fractured, medical examiners have missed skull fractures before.

The question of suicide versus murder would be addressed, if not cleared up, by exhumation and a second autopsy to examine whether Hinton’s head injury occurred before or after death and whether the skull is fractured. “That would cost somebody thousands of dollars and not turn up anything,” Flomenbaum says. It’s a process, though, that the family considered initiating shortly after Hinton’s funeral in November 1992.

According to Mark Zaid, a Washington, D.C., attorney working on the John Wilkes Booth exhumation case currently pending before the Maryland Court of Special Appeals, “It is a simple process that can be made complicated if someone wants to make it so.”

First, all immediate family members must agree to request exhumation, then approach the cemetery with their request. If the cemetery agrees, all the family needs is permission from the jurisdiction’s state’s attorney’s office and money to pay for the exhumation and examination. If the cemetery rejects the request – and that doesn’t happen in most cases, according to Zaid – the family can go to court.

Another possibility for obtaining more clues to help solve the Hinton mystery is disclosure of more reports of investigations into the circumstances surrounding his police work and his disappearance and death. The autopsy report, Hinton’s police personnel file, and Stanton’s questionable-death report have been released. As Hinton’s court-appointed representative, Francine also plans to obtain copies of documents subpoenaed (but never released) in the Eric Thomas drugs-and-firearms case: two IID files (one on the alleged Thomas burglary, the other on Hinton’s death), and records of a probe by the Baltimore City State’s Attorney’s Office, including grand-jury testimony about the alleged Thomas burglary. She also intends to request all other Hinton-related police information to which her husband would be entitled if he were alive.

In New York, NYPD spokesperson Detective Julio Martinez told CP that “the case is under active investigation” and the report of its questionable-death investigation on Hinton will not be released. “Obviously, this is an unusual case and the chief of detectives is not going to comment on it until all aspects of it are cleared up,” Martinez says. He also declined a request to interview Joseph Burdick, the NYPD homicide detective who was assigned the case back in 1992.

In addition to the evidence reported here, the family’s suspicions of foul play are provoked by disputed facts, street talk, and innuendo-laden coincidences that suggest to them the documented record of Hinton’s disappearance and death is woefully inadequate. Recollections and questions about Sean are part of the Hinton’s daily routine. “There’s not a day that goes by I don’t think about Sean,” his mother Jean says.

Hinton’s friends also wonder about his death. “It’s hard for me to believe it was suicide because Sean wasn’t that type of person,” Forrest Lee Moore says. He believe Sean was more likely to face his career problems and start anew than to kill himself over losing a job, especially since he was so young, so hard-working, and so easy to get along with. “If you met Sean, you would like him right off the bat,” Moore comments. “Everybody liked him.” Robert Templeton, Hinton’s friend and former boss, is more adamant: “The whole thing stinks from beginning to end,” he says.

Hinton’s family and friends continue to believe that many of their questions will eventually be answered. “Sooner or later, it’ll all come out,” Jean Hinton likes to say. But neither she nor the rest like the wait.

“I haven’t had no comfort since Sean’s been dead,” Jean laments. “That prayer didn’t get answered.”