By Van Smith

Published in City Paper, July 30, 2008 (Photo from Baltimore City Police Department)

“Come here with an ambulance, quick!”

15-year-old Ronald Alberto Hinton cries over the phone to the 911 operator just after noon. “My little cousin fell on the porch, hit her head, she ain’t getting up. Come on, hurry up!” Seconds later, he tells the operator she “fell and hit her head on the ground.” When the responding medics and police arrive, Hinton, who is the baby sitter, tells them that 4-year-old Ja’niya Ebony Woodley fell while jumping on the bed.

Hinton is at 2908 Goodwood Road in Northeast Baltimore, a house rented by his uncle Leland Slater and Slater’s longtime companion, Deborah Wall, who are the unconscious girl’s grandparents. Daikwon Eaddy, the girl’s 7-year-old brother, is the only other person at the house when the authorities arrive. He corroborates the fall from the bed, but his version differs from Hinton’s on where she landed.

The first responders quickly conclude the child’s extensive injuries–the most obvious are that her face is black and blue and swollen, her lower lip is busted, and there are bite marks on her chest and thigh and bruises all over, especially on her thigh and back–resulted from child abuse, some of it sexual. The boys’ stories don’t hold up. One of the medics, according to her statement in the Baltimore Police Department (BPD) homicide file of the case, says that “seeing the bruises, I knew that no matter how high the bed was, the bruises were older than what [Hinton] made them appear to be.”

Shortly after 1 p.m. on June 21, 2006, the victim is transported by ambulance to Johns Hopkins Hospital in East Baltimore, where Dr. Jamie Schwartz examines her and tells Baltimore police detectives that her injuries “are not accidental,” noting her condition: “critical with minimal brain activity, a bite on her nipple, old bites on chest, and left thigh.” Injuries to the vaginal area are also observed, and a kit used to gather evidence of rape is administered, including a swab to test for genetic material left in the bite marks on the left thigh.

Also arriving at the hospital are several of the victim’s relatives, and a chaotic scene soon erupts when the child’s actual parentage becomes known to shocked family members for the first time. Her name is not Ja’niya Woodley, it turns but, but Ja’niya Williams. Tempers flare as the child’s mother, Joy Eaddy, is caught having lied to Keenan Woodley, who up until that moment thought he was Ja’niya’s father, and John Williams, the child’s actual father, who learns suddenly that Keenan Woodley was also helping to raise the child. The shift in the family tree also means Hinton is not Ja’niya Williams’ cousin, as he thought when he called 911 a couple of hours earlier, and that Slater and Wall are not her grandparents.

A city Department of Social Services (DSS) social worker attempting to interview family members reports that she encounters rage and indignation as they start “yelling they did not abuse” the victim. Joy Eaddy does “not show any signs of remorse, sadness or concern” over her daughter’s injuries, and is “quickly angered” and refuses “to answer any more questions.” A distraught Wall tells paramedics and the police that the child is not abused and that her only injuries occurred the day before, when she fell into a fan and hurt her head. Another DSS caseworker informs police that Joy Eaddy “has a DSS history of child neglect,” without providing details, but tells them that Daikwon Eaddy “was to have no contact with his mother . . . until further notice.”

At police headquarters downtown, at 10 p.m. later that night, Hinton sits in a waiting room with his mother, Francine Toney; he’s been there since shortly before 5 p.m. Daikwon Eaddy is there, too, in Slater’s care. They are waiting to speak with two detectives–William Wagner of the child-abuse section and homicide investigator Todd Corriveau–who have just arrived after spending the afternoon and evening at the hospital, gathering information about Ja’niya Williams’ injuries and family circumstances. At quarter to midnight, after taking a statement from Slater, the detectives start to tape their interview of Eaddy.

Eaddy, the detectives write, says Hinton was “slamming [his sister] on the bed” and “kept on messing with her,” even though “she kept crying for me” to help and Eaddy was telling Hinton to “Stop! Stop!” He describes his sister as “unconscious,” “bleeding from her nose and mouth,” and as having “many bruises on her body.” Eaddy recalls Hinton “was holding his sister’s hands and shaking her,” and also “dragging his sister on the steps inside the home.”

At 12:06 a.m. on June 22, right after Eaddy’s statement is taken, Corriveau writes in his log of the investigation that “Ronald Hinton is now a suspect,” though Hinton and his mother do not know this.

At 12:35 a.m., Hinton is advised of and waives his Miranda rights in the presence of his mother, who is then ushered away. The detectives begin an hourlong preliminary interview, which is not tape-recorded. At 1:36 a.m., they turn on the tape recorder and go over it all again for posterity.

Wagner writes in the charging papers that Hinton confessed to “performing cunnilingus on the victim, fondling and digitally penetrating the victim’s vagina with his fingers, and putting his penis partially in the victim’s vagina. The defendant also bit the victim on her right breast and bit the victim twice on her left thigh. He struck her multiple times with an open hand to the face. At one point the victim ran downstairs and he pursued. He caught her and carried her back upstairs, retrieved a black belt from a closet and beat her with it.”

The detectives note that “Hinton provided information that only he–the suspect–had knowledge of, such as the exact injury to the victim’s body and how her injuries were inflicted,” though the detectives, too, know Williams’ injuries.

At 3:15 a.m., Hinton is charged with rape and assault and put in temporary lockup at the Central District police station. At 4:10 a.m., Corriveau checks to see if Ja’niya Williams is still alive. She is, though she never regains consciousness and dies of her brain injuries on June 23. The next day in the early evening, after the medical examiner rules her death a homicide, murder is added to the list of Hinton’s charges.

When Hinton is transferred to the Central District Intake Facility and is preparing for his bail-review hearing on June 26, his cousin, correctional officer Robin Smith, recognizes him. She looks at his paperwork and listens to what he has to say. “They said I tried to murder somebody,” Smith recalls Hinton saying. “I didn’t do it,” he continues, crying. “They made me sign something, and [said] if I didn’t I would never get to see my mother again, and I’d never go home. They forced me. They made me say I did it, but I didn’t do it.”

After listening to Hinton’s story, Smith gives him some advice: “Don’t talk to no one if they’re not your mother or your lawyer.” She also tells him not to show his charging papers to anyone, warning him that “papers like that can get you killed in here.”

When Ja’niya Williams’ autopsy is conducted on June 24, the medical examiner, Dr. Laron Locke, fills out a diagram with front and back views of a human body. It is used to indicate and describe her external injuries, and it is crowded from her head to her knees with circles and dots connected with lines and arrows to short descriptions of what is observed at various locations. Regarding the head, the notes say: “Whole forehead = general bruise,” with “minor scratches” and a “bruise” around the eyes, while both cheeks are described as “swollen” and the left lower lip is “swollen” with a “small cut” inside.

Corriveau attends the autopsy and compares the findings with Hinton’s confession. He learns that she died as a result of suffering a subdural hematoma, in which veins inside her cranium ruptured, causing blood to constrict and ultimately shut down her swelling brain. Corriveau writes in his summary of the autopsy that this, along with “general blunt force injury to her head,” is “consistent with suspect’s confession that he `beat’ the victim about her head.” He also points out that “skull not fractured; no specific contact `point of impact’ on victim’s head,” and that there are no signs “of any type of strangulation/smothering.”

Corriveau continues his comparison. He notes “abrasions to outside of vagina,” and is reminded that Hinton said he “put his fingers/penis in/on and `rubbed’ victim’s vagina.” He finds the bruising observed at the entry of her vagina, along with the fact that her hymen is intact, consistent with Hinton’s admission “that he `only put it in a little bit.'” Hinton said “he hit her in her bottom lip with his hand,” which explains the swollen, cut lip. The bite marks–on the right breast and on the left thigh–correspond to Hinton’s statement that he “bit her `on her right breast'” and “repeatedly” on the left thigh. The “small linear abrasion to lower back,” Corriveau surmises, is “possibly caused by belt striking her, per suspect’s confession,” and the “bruising and/or possible faded bite marks to right rear buttock” is “consistent with suspect’s confession that he struck her in buttocks with belt.”

Many of Williams’ injuries do not directly correlate to Hinton’s confession, Corriveau notes. The “swollen cheeks,” the “general redness/bruising to forehead,” the “minor scratches/bruising to eyes & in between eyes,” the “bruising to right shoulder,” the “scratch on right arm,” the “bruise to front of right thigh,” the “abrasion to left clavicle,” the “abrasions/contusion to left rear shoulder,” the “bruising to inner left bicep/outer left bicep,” the “bruise” on the “left forearm,” the “scratches/bruise to left hand/wrists,” and the “large contusion/abrasion to middle top back”–these aren’t explained by Hinton’s description of how he injured Williams.

The bite marks on Williams’ body, Corriveau writes, “appear more similar to severe `hickeys’ than to actual puncture wounds or tears to her skin.” But, he adds, “the shape of a mouth is clearly seen on the bite marks, with some spots having clear indications where teeth touched the victim’s skin.” So Corriveau has the medical examiner prepare photographs of them, to scale, “for future comparison purposes to the suspect’s teeth.” The photos, he explains, “will be a better indicator” for comparison that “actual cut-out samples of the victim’s skin,” given the skin “not being drastically broken by the bite marks.”

Two days after the autopsy, Corriveau contacts forensic odentologist Warren Tewes, of the University of Maryland, and discusses with him the possibility of getting “dental molds of the suspect’s teeth, via search warrant, for comparison purposes to the photos of the bite marks on the victim.” On June 28, Corriveau meets with Tewes, who says that dental molds of Hinton’s teeth–which ultimately were not obtained–“are not applicable” for comparing to the photos because the bite marks “have a `lack of definition’ that is necessary for effective and conclusive comparison purposes.” However, Corriveau continues, “Tewes provided general, basic information regarding the bite marks on the victim’s skin that may or may not be of relevance for court and/or testimony purposes” at trial.

The day of the incident, police seize all manner of property from Slater and Wall’s home: sheets, pillows, towels, comforters, a washcloth, a T-shirt, a pair of panties, a pair of flip-flops, a cap, and a pair of shorts with blood on them. They also take swabs of suspected blood from a dresser, a bathroom, a foot stool, and a wall. On June 24, they return and retrieve a belt with “possible blood stains.” Hinton told police about the belt during his confession two days earlier, but the warrant is served only after the autopsy “corroborated the suspect’s claim that he beat the victim with a belt (mainly a 2-3 inch linear abrasion on her back, as well as other bruises on her body),” Corriveau writes in his reports.

After getting the blood and DNA profiles of Ja’niya Williams and Hinton, whose fingerprints are also obtained, Corriveau on July 5 asks for lab work to be done on the seized property. He orders that the belt be analyzed for possible fingerprints and blood, and also asks for the blood on the shorts and the four blood swabs taken from the house be compared to Hinton’s and Williams’ blood. The DNA comparisons he asks for are from a hair found on a sticky pad from the victim’s body at the hospital, and from the swabs taken from Williams’ bite marks, vagina, and anus. He explains that these swabs, which were taken “approximately four hours after” the incident, “are most likely better samples for comparison purposes” than those taken at autopsy three days after Williams arrived at the hospital.

Meanwhile, Corriveau spends the midmorning of June 24 canvassing neighborhood residents. He writes in his report that several of them say they already told news reporters their thoughts about Ronald Hinton, which are, as Corriveau summarizes them, that he “has a history, over the past 4 years (approximately), of violence, lying, abusive language, and sexually charged comments to neighborhood women.” The residents request anonymity and don’t give recorded statements, though Corriveau has their names and contact information. Later that day, he phones a DSS Child Protective Services worker and e-mails BPD public-information officer Donny Moses to inform them of his findings.

Twice more, on July 3 and July 9, Corriveau visits the neighborhood to collect firsthand knowledge of Hinton’s past behavior from four more nearby residents. They, too, ask to remain anonymous. They tell him Hinton is “easily argumentative,” “very confrontational,” and that he “has been seen `beating on’ his `little brothers and sisters’ in his front yard until they either ran away or until `his big brother’ physically stopped him from doing so.” They recall that Hinton “strangled their son approximately 5 years ago, by using both his hands to squeeze their son’s throat, and that suspect had to be physically pulled from their son.”

(Toney reacts to the details of the neighbors’ anonymous accusations with indignation. “It makes me furious,” she says. “We weren’t really welcome to the neighborhood when we moved” there in the mid-`90s, she observes, and alleges that her family has periodically been subjected to racist comments from neighbors. She says her son has taken his share of guff around the neighborhood over the years, and that at times he’s taken the bait–such as the time several years ago that another neighborhood child “hocked spit in his face,” and they fought. But as for the contention that he beat up his younger siblings, Toney says “that didn’t happen.” And she dismisses the suggestion that he makes sexually inappropriate comments as the neighbors “just trying to make him out to be a monster. He did things some children do, he’s not perfect, but that he’s this monstrous thing–I won’t accept it.”)

Corriveau finds that Hinton has no prior juvenile criminal record, though he was the victim of an alleged aggravated assault two years earlier. And a review to see if he has a record of any “citizen contact receipts”–documentation of police-initiated interactions that don’t result in charges–turns up nothing.

On July 10, Corriveau joins the prosecutorial team handling the case–Baltimore assistant state’s attorneys JoAnne Stanton and Temmi Rollack–to interview Daikwon Eaddy at his mother’s home. He arranges the meeting “in order for Stanton and Rollack to meet” the young boy, “ask him preliminary questions regarding the incident in question, and to obtain a `feel’ for him, in terms of his pending court testimony.” The star prosecution witness has a surprise for them.

“During the meeting,” Corriveau writes, Daikwon Eaddy “disclosed that on the day of the incident in question, suspect Ronald Hinton beat him with a belt (previously undisclosed).” Two other people, whose names are redacted from Corriveau’s report, recall that “each observed marks on his back, consistent with being hit with a belt” when Eaddy returned to his grandmother’s house after his June 21 interview with police.

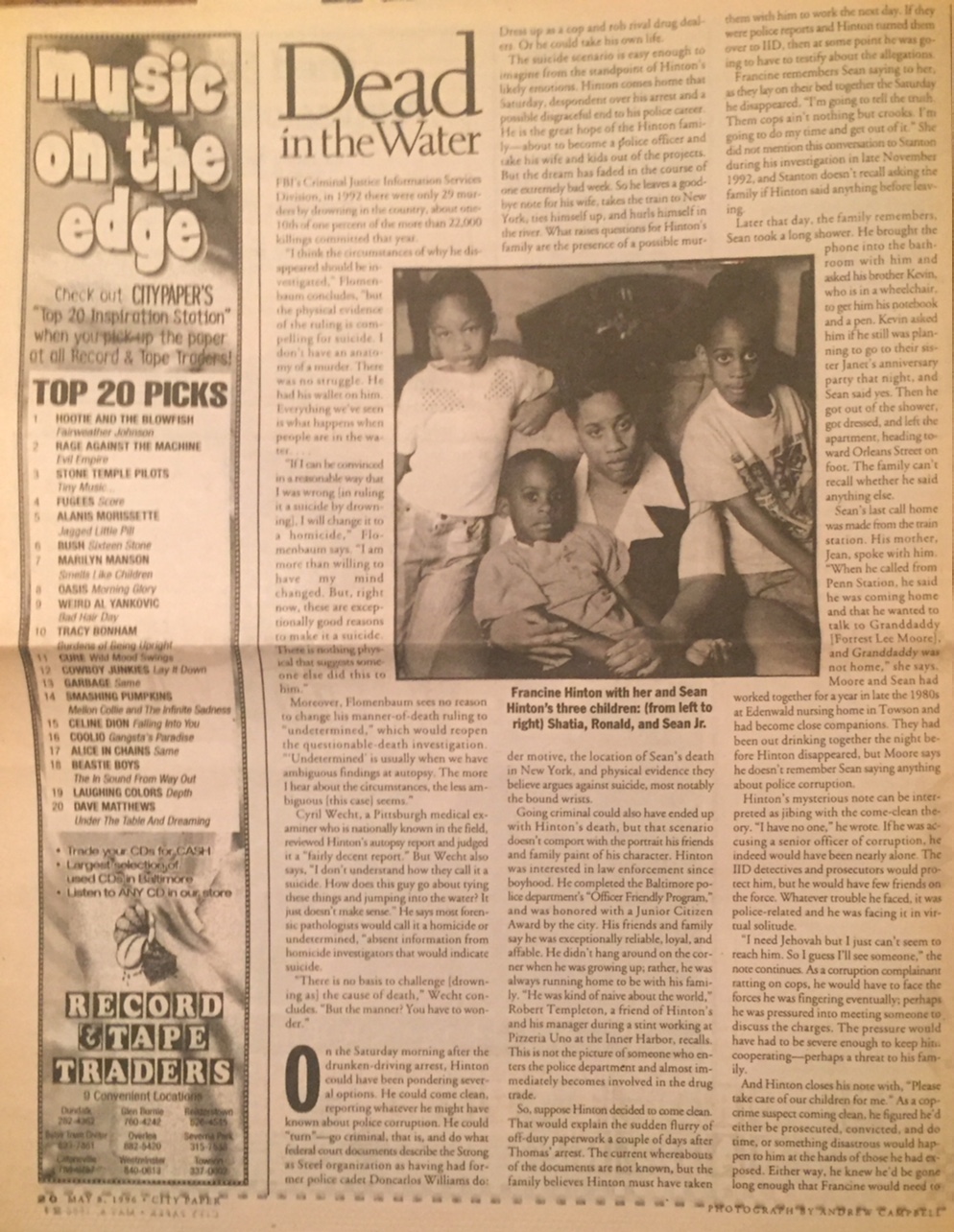

In December 2006, Francine Toney calls City Paper. It is not the first time she’s been in contact with the paper. More than a decade ago, City Paper published an extensive, investigative cover feature and two follow-up news articles about the 1992 death of her husband, Baltimore police trainee Sean Hinton, who was Ronald Hinton’s father (“Dead in the Water,” May 8, 1996; “Another Look,” Mobtown Beat, Dec. 4, 1996; “Questionable Death,” Mobtown Beat, June 4, 1997). Over the intervening years, she stayed in touch, but attempts to reach her after Ronald Hinton’s confession had been fruitless: She’d changed her phone number and moved. Now she’s on the phone, and the emotions are running high.

“The DNA [analysis of evidence in Williams’ homicide] came back, and Ronald couldn’t have done things he confessed to,” Toney explains. “The detectives told me, `The DNA will show everything,'” she continues, in tears. “Now it’s back, and it shows he didn’t do it!” She asks if police would go out and find who killed Williams, now that it was obvious her son didn’t. When asked why he confessed, she says, “he’s afraid of police because of what happened to Sean [Hinton]. The detectives balled up their fists and threatened him, and told him he could go home if he said he did it. He just wanted to be out of there.”

Toney says she does not have all the details, but she knows this much: Ronald’s DNA was not in the bite marks; somebody else’s was. “He didn’t bite her,” Toney says. “Somebody else did. And there’s other people’s DNA at other places, too, different people.” She adds that since her son has been held in jail, turmoil between the two families has been taxing, but the new DNA findings are “going to make things worse. Who did these things to that poor child?”

Toney takes out a second mortgage on her house to hire Janice Bledsoe as her son’s criminal-defense attorney in early 2007. She invites a City Paper reporter to go with her and several members of her family for a February 2007 meeting about the case at Bledsoe’s office. Color photographs of Ja’niya Williams lying face up in a Hopkins hospital bed are reviewed, prompting remarks (including by this reporter) that some of the bruises look less than fresh. No one in the room is an expert on such matters, but everyone bruises, and therefore knows that bruises change color over time. Some of Williams’ many bruises appeared to have a greenish-yellowish hue, suggesting some time had passed since they were sustained.

If someone’s DNA other than Hinton’s is in the bite marks, and if Williams’ sustained earlier injuries when Hinton was not present, then Toney and the rest of Hinton’s family have hope that perhaps his confession can be overcome at trial. The jury is going to need an explanation of why Hinton confessed falsely, and the one that Toney suggests–his deep-seated fear of police, because of what he believes about his father’s death when he was an infant–is the only one available.

During the weeks after the incident, the issue of prior injuries to Williams is brought up during Corriveau’s interviews with family members, as transcribed in the homicide file. He asks the witnesses if Hinton has been the children’s baby sitter on prior occasions, and if any injuries were observed at those times. He learns that Hinton has, and that no injuries were noticed before–except on the day before the incident, and Corriveau gets different versions of the story.

Deborah Walls, at the hospital on the night of the incident, is on record mentioning that Williams had injured her head in an accident with a fan. But when she’s interviewed later by Corriveau, she tells it differently. “When I got home I noticed a hickey on her forehead, on her left side,” Walls says during a July 1, 2006, taped interview. “I said, `Where did you get that?’ And she said she had fallen getting a towel, and I got right on the phone immediately and called her mother and let her talk to her mother. I tell her mother any time they got injured playing or anything, that’s the first thing I did.” By “hickey,” she explains, she means “a bump, as a bump on the head.” She says Ronald Hinton told her that “[Ja’niya] fell.”

Leland Slater is also interviewed on July 1, and in his version, it’s the fan that hurts Williams, but on her back rather than her head. He recalls he was in the kitchen with other family members on the night before the incident, and somehow Williams’ shirt rode up her back. He says he saw “marks on her back,” and when Williams was asked about them, he recalls Ja’niya saying that “I was upstairs” and “I fell over the fan.”

The conflicting explanations of the nature and cause of Williams’ injuries the day before raises the question: Are there any other indications that some of Williams’ injuries may have happened before June 21? And there are. The medic, for instance, who helped treat Williams before she arrived the hospital, and who told police she thinks some of the “bruises were older.” And Dr. Schwartz at Hopkins, who described “old bites on chest, and left thigh,” a phrase that was used in the charging documents and search-warrant affidavits in the case against Hinton. Corriveau himself, in his report about the autopsy, describes “bruising and/or possible faded bite marks to right rear buttock” (emphasis added).

Corriveau clearly suspected Hinton had abused Williams before, but witnesses didn’t corroborate that idea. As a result, his investigative record suggests Williams had older injuries–including at least some of the very bite marks that Hinton confessed to giving her.

Raising the importance of the bite marks even further is the fact that the ones on the upper left thigh were swabbed and came back positive for the presence of DNA belonging to an unknown person other than Hinton. Yet the homicide file has nothing in it to suggest investigators even considered taking steps to try to identify that person. Nor are there any indications in the file that attempts were made to learn the source of the DNA recovered from a variety of other locations on the tested evidence belonging to people other than Hinton.

After all, who needs DNA when you already have a confession?

“Ronald Hinton is the son of Sean Hinton and Francine Toney,” Bledsoe tells the Baltimore City Circuit Court jury. She’s five minutes into her opening statement on the first day of the trial, April 23, 2008, and she is trying to tell the jurors why, if Hinton didn’t rape and beat Williams, he would tell the police he did. “The Hinton family has an unusual history,” Bledsoe says. “Sean Hinton was a police officer–”

“Objection,” Stanton says.

Bledsoe shrugs in frustration as she and Stanton approach the bench to argue before Judge John Addison Howard. Stanton hardly says a word in the ensuing debate, though, as it is apparent that Howard has already made up his mind: Bledsoe won’t be allowed to discuss Hinton’s father in front of the jury.

“It’s a bunch of hooey and a lot of hearsay,” Howard tells Bledsoe during the bench conference, “and you’re not going to be able to go into it.”

Bledsoe explains the situation to Hinton and his family out in the hallway–that the main thrust of his defense was just yanked out from under him. She adds that it is even worse than that, because the jury, having heard only half of her sentence, is left with the impression that since Sean Hinton was a police officer, his son would have strong reasons to trust the police, not to fear them. The last guilty-plea offer from the prosecutor, prior to the beginning of the trial, was 20 years of imprisonment, but Hinton and his family still don’t want to take the deal. Ronald is innocent, they say, and they want a trial. So the trial continues.

The tape of Ronald Hinton’s confession is played. Though it doesn’t appear in the transcript–and though Corriveau and Wagner testify that once they turned on the tape recorder, they never turned it off again until the confession was over–Bledsoe points out to the jury that the very beginning of the tape has a split-second of a human voice loudly saying, “Stop messing with me!” It sounds like Hinton’s voice.

Corriveau insists that he didn’t use leading questions when interviewing Hinton, didn’t suggest Williams’ injuries so that Hinton had the information he needed to admit to details about the injuries that Corriveau knew from visiting her in the hospital–and then Bledsoe proves he did on two occasions, when Corriveau asked Hinton whether or not he put his hands between Williams’ legs and his fingers in her vagina. Corriveau explains that Hinton had already provided that information in the preliminary interview.

Wagner testifies that he took notes rather than record the preliminary interview in order to have a complete record–and then admits that, yes, recording the preliminary interview, too, would have provided a more complete record of what transpired in the interview room. (Hinton’s false-confession claim was included in a City Paper article [“Fess Up,” Mobtown Beat, Jan. 23] about a law that passed in Maryland’s 2008 General Assembly session requiring police to videotape all aspects of interviews with suspects in murder and sexual-assault cases. The law is intended to help create foolproof confessions, while also assuring police interviews are on the up-and-up.)

Corriveau’s theory that Hinton had abused Williams on prior occasions does not come up at the trial. In fact, other than the “hickey” on Williams’ forehead, no one–not Corriveau, not the medic, not Dr. Schwartz–testifies that they observed any signs that some of Williams’ injuries may have occurred before the harm Hinton confessed to inflicting. Under cross examination, though, the medical examiner admits the possibility that Williams’ death could have been caused by more than one brain injury in succession. In other words, it’s theoretically possible that whatever harmed Williams’ head on June 21 may have worsened a brain injury that occurred earlier.

The conflicting stories used to explain Williams’ hickey–was it tripping on a towel, falling into a fan, or both?–are not brought up for the jury. Nor is there any mention of the marks on her back that Slater said he observed in the kitchen the night before the incident. In fact, Slater doesn’t testify at all. Whatever became of Corriveau’s attempt to compare Hinton’s dental pattern to Williams’ bite marks also is not in evidence at the trial.

Daikwon Eaddy, now 9, gives confusing testimony broken up by bathroom breaks and a tearful inability to answer questions. He says nothing about Hinton beating him with a belt, and though his testimony describes menacing behavior by Hinton, he does not say Hinton committed the violent acts he’d told investigators about the night of the incident.

At one point, Judge Howard comes down off the bench, crouches next to Eaddy, and has a quiet conversation with him in front of the jury. “You’re doing good,” the judge tells him. When Bledsoe asks twice for a recess, so the jury won’t continue see Howard giving Eaddy a pep talk, the judge gets testy: “I heard you the first time, Ms. Bledsoe.”

The DNA evidence is presented, including a dramatic cross examination of the DNA expert by Bledsoe’s partner, Sandra Goldthorpe, who reveals to the jury that the DNA in the bite marks not only isn’t Hinton’s but that it’s a female’s. All told, six of the analyzed items excluded Ronald Hinton’s DNA, but included the DNA of others, male and female. If any of the jurors want a solid basis on which to build reasonable doubts about Hinton’s guilt, it is the DNA evidence. But they still have the confession to consider, and they still don’t have an explanation for why anyone would lie about such things.

The prosecution team wraps up its case, and Ronald Hinton takes the stand in his own defense. He accuses Corriveau and Wagner of threatening to beat him up in the interview room if he didn’t confess. “That’s when I kept on telling them, like, `Leave me alone,'” Hinton testifies. “And that’s when I said I didn’t do nothing. That’s when they said, `If you tell us you did it, we’ll let you go home.’ I thought I was going to go home, because I was scared, because I thought something was going to happen to me, because I don’t like police officers, and the reason I don’t like them–”

“Objection,” the prosecutor says.

“Sustained,” the judge says.

Bledsoe tries to elicit Hinton’s response in a variety of ways and is blocked two more times by sustained objections before the judge allows her line of questions to continue.

Bledsoe turns to Hinton and asks, “Why were you afraid?”

“Because my father,” Hinton answers, “he was killed by policemen, even his own partners.”

That’s all Ronald Hinton’s jury heard about his father’s story: two mentions on either end of the trial, with no details, no context, and no questions asked or answered. It’s a case that stands out in the memories of many Baltimore police officers, and it has deeply haunted the Hinton family.

Sean Hinton was 22, weeks away from his city police academy graduation, and had just undergone field training in the Western District with police officer Stanley Gasque. On Oct. 24, 1992, a Friday night, Hinton had a minor car accident downtown and was arrested and charged with driving under the influence of alcohol. The next day, after getting his car out of the tow lot, he walked out of his home. His last contact with his family was a phone call from the Amtrak station in Baltimore to his family.

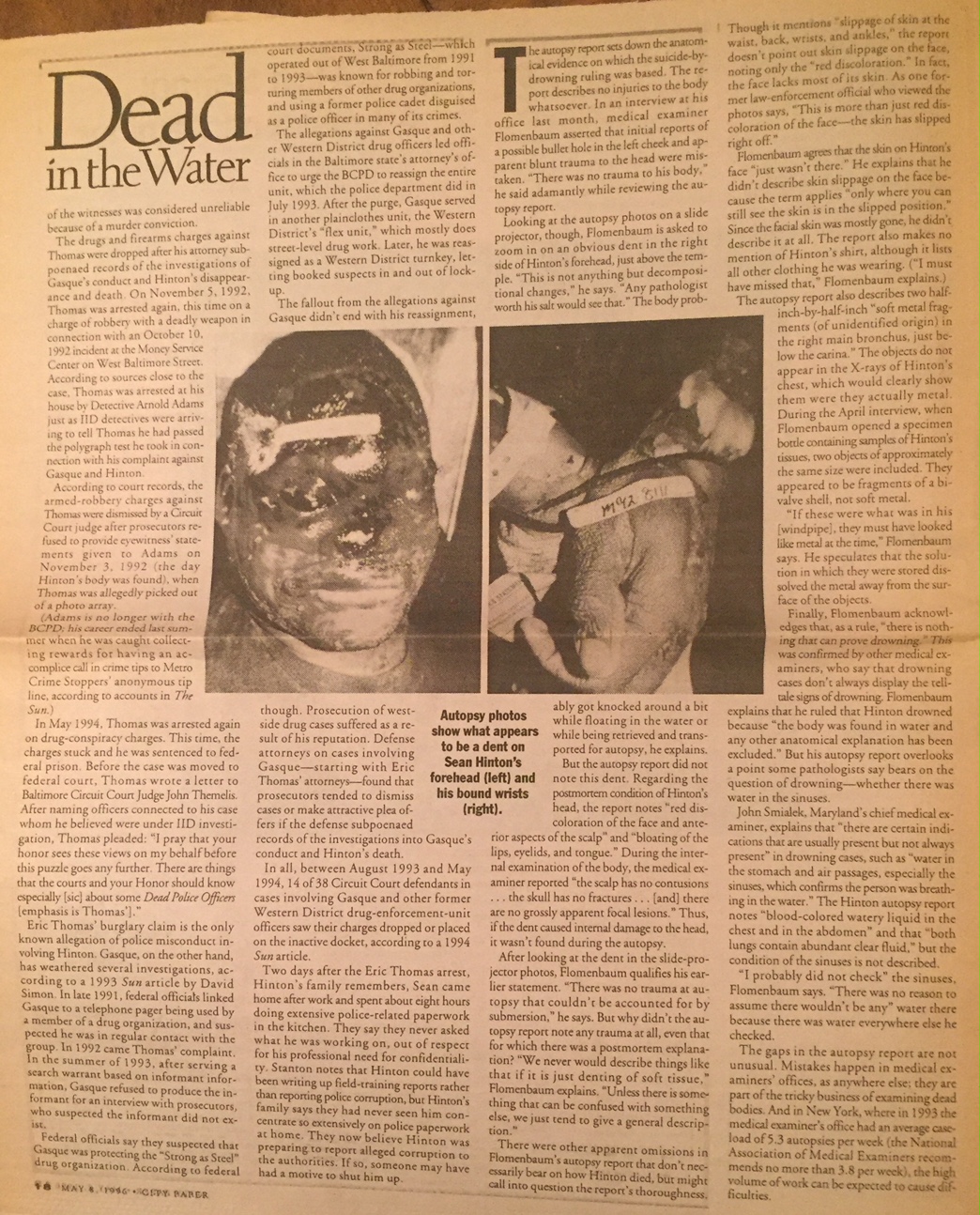

Ten days later, his body was recovered from the New York Harbor off Battery Park in lower Manhattan. His wrists were bound tightly in front of his body with the drawstrings of a jacket, and though the autopsy report did not note head trauma, it appeared evident in the accompanying photos. His fingers and hands still had skin on them, though it had slipped a bit, but his swollen, misshapen face was devoid of skin from the scalp to below the chin.

New York medical examiner Mark Flomenbaum, after three weeks of consideration and after learning from the Baltimore police that what was characterized as a suicide note had been found, on Nov. 27, 1992, ruled the case a suicide by drowning. He attributed the condition of the body to the postmortem effects of floating in the water.

City Paper published photos from Hinton’s autopsy, with his family’s permission, in the 1996 article titled “Dead in the Water.” It explored a variety of facts that Flomenbaum did not have at his disposal when he made the suicide ruling, including the contents of the letter he left for his family and the very suspicious circumstances involving Hinton and Gasque that occurred the week he disappeared. Those circumstances involved accusations that together they robbed a drug dealer in West Baltimore, and that federal law enforcers suspected Gasque was protecting a drug organization known for torturing and robbing other drug dealers. It took years of investigating before, ultimately, nothing came of the accusations against Gasque and Hinton.

The members of Sean Hinton’s family, though, say they have no doubt that he was murdered before he shared information about unaddressed police corruption. The story is fact in the Hintons’ minds, even if it never can be proven. And their interpretation of the fact that the BPD mounted a 21-gun salute at Sean Hinton’s funeral–a rare police honor–is that they’re not the only ones who believe Hinton was killed in the line of duty.

Not so the jurors, who learn nothing of the family’s story, nor of the facts about Sean Hinton’s death. They also have no expert testimony to explain the female DNA in the bite mark–though Stanton, in closing arguments, assures them that it was attributable to contamination during Williams’ medical treatment. And she points out that, at the end of his confession, Hinton apologized–something, she argues, an innocent suspect would not do. After four hours of deliberation, the 12 jurors unanimously decide Hinton’s confession was true and voluntary, and on May 5, 2008, they convict him on all counts.

On July 21, Ronald Hinton is sentenced to life in prison, plus 25 years. He files an appeal the same day, and in June he sends a letter from jail to the Innocence Project, a group that uses DNA and evidence of false confessions to work for the release of innocent convicts. To date, Toney says, Hinton has not heard from the organization.

“If the DNA matched, I would accept that he did this,” Francine Toney says of the case. “It doesn’t, so I still believe he said he did it because he’s so afraid of the police.”

If the appeal succeeds, Hinton might get a crack at another jury. If not, he’s in for the long haul, serving life for the rape and murder of a child–crimes that tend to put an inmate convicted of them in low esteem among fellow prisoners. If he didn’t do it, that’s a particularly hard position to be in. If he did, well, prison authorities are responsible for keeping him safe, as best they can.

“I got a letter from him,” Toney explains over the phone on July 25. “He’s in a cell by himself, with two shelves and a bed. The bed is comfortable, and there’s enough room for him to pace back and forth and pray to God.”

She starts to cry. “It hurts me, because I feel so helpless now that I can’t help him. It’s so sad. Ja’niya is gone, and that hurts me, too. But what about the DNA? The prosecutor said [to the jury] don’t worry about the DNA, the DNA doesn’t matter in this case. Well, what’s so different about Ronald’s case?

“I am so tired of the falsehoods about my family–my husband killed himself, Ronald did this to Ja’niya, Ronald is abusive. I am just not going to accept it. If the DNA matched, I’d have no choice to accept it. But it didn’t, and I won’t accept it.”

Ja’niya Williams’ father, John Williams, speaks to a reporter on July 26, while working at his job as a drug-store security guard. He has no doubts whatsoever that Hinton did it. Asked about prior wounds on his daughter’s body, especially any bite marks, Williams says: “I know about that. She got bit on her arm, playing with her cousin a few days before,” indicating his left bicep. When informed that others observed older bites and bruises at other locations, and that the jury did not hear about that evidence, Williams sticks to his guns. He’s 100-percent certain they’ve got the culprit behind bars.

“That boy boxed himself in,” Williams observes. “I would never, ever say I did anything I didn’t do–especially something like that.”