The World War broke out. My business was at a low ebb, as it was summertime, and I was not “in” with the powers that be in my profession. I was not on the outs especially, but was not particularly on the ins.

After dreaming around for a while, I decided to try to get into the game, although my age was against me. I closed the office and left the keys with Dr. Mears, a neighboring physician, an started sorth. I thought the chance of getting into the Navy were better away from home, so I landed at Portsmouth, Va., and took a room near the Navy Yard. I took some of Dr. Steiner’s books alone, and read them every day, especially trying to digest his Philosophy of Freedom.

I visited the Navy Yard, and the surgeon in charge, Dr. Smitt, was very nice to me, as he was to all physicians. But I saw no chance of getting into the Navy because of my age.

From here it was not far to Washington, where I went one day to see what I could do there, but with no greater success. On the way up the boat was full, many sleeping on the cabin floors.

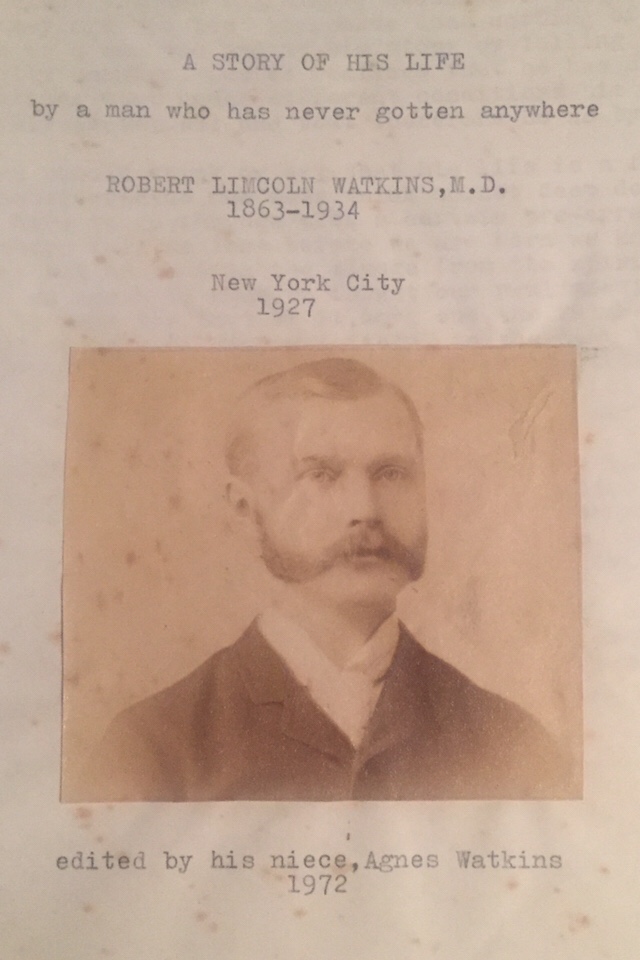

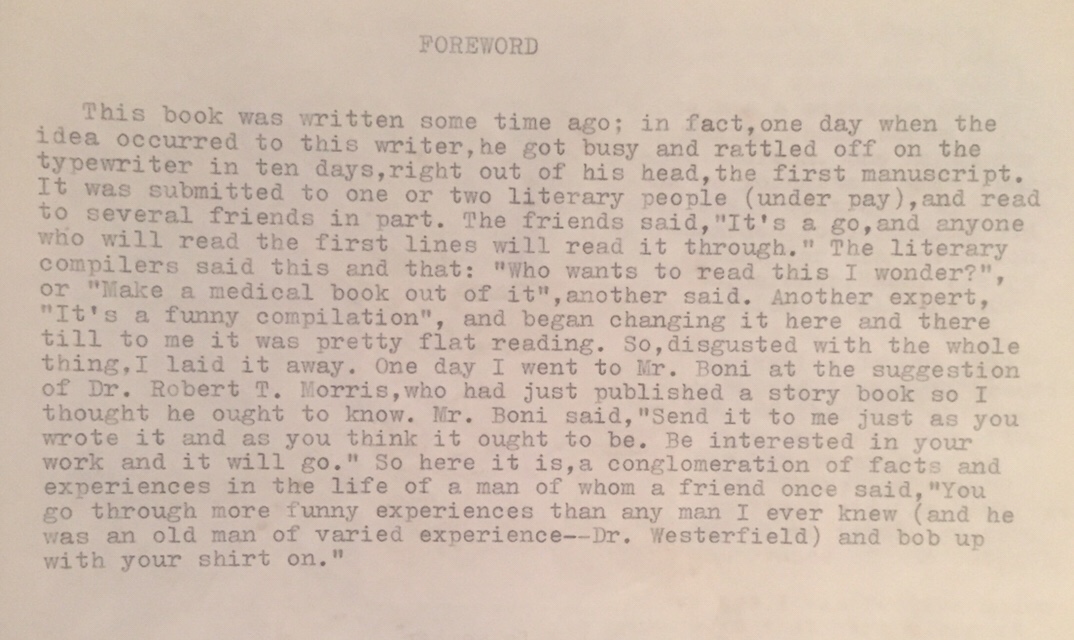

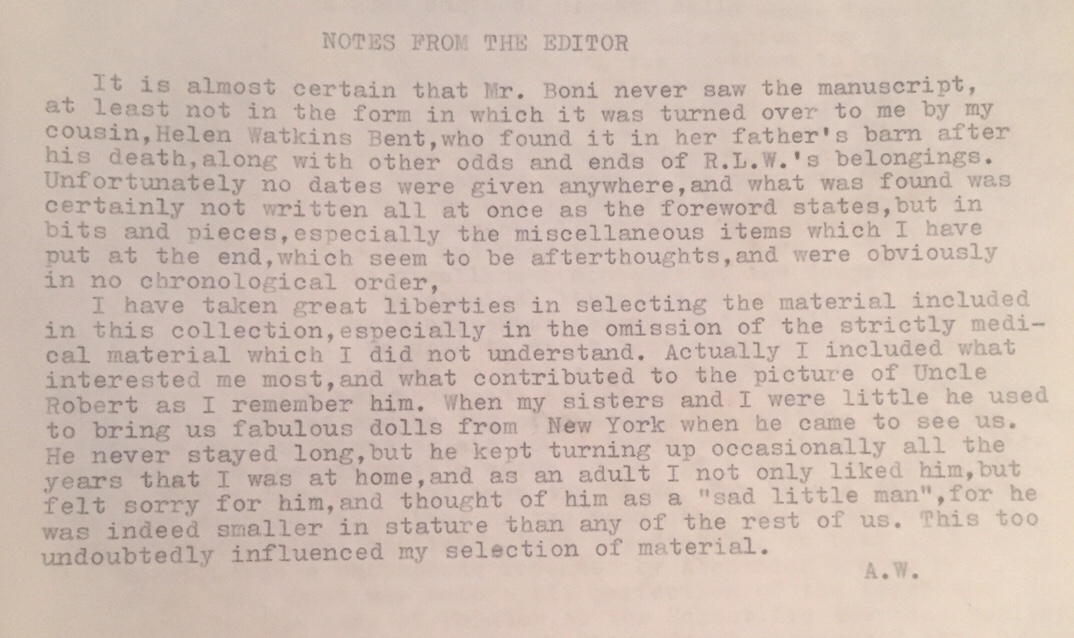

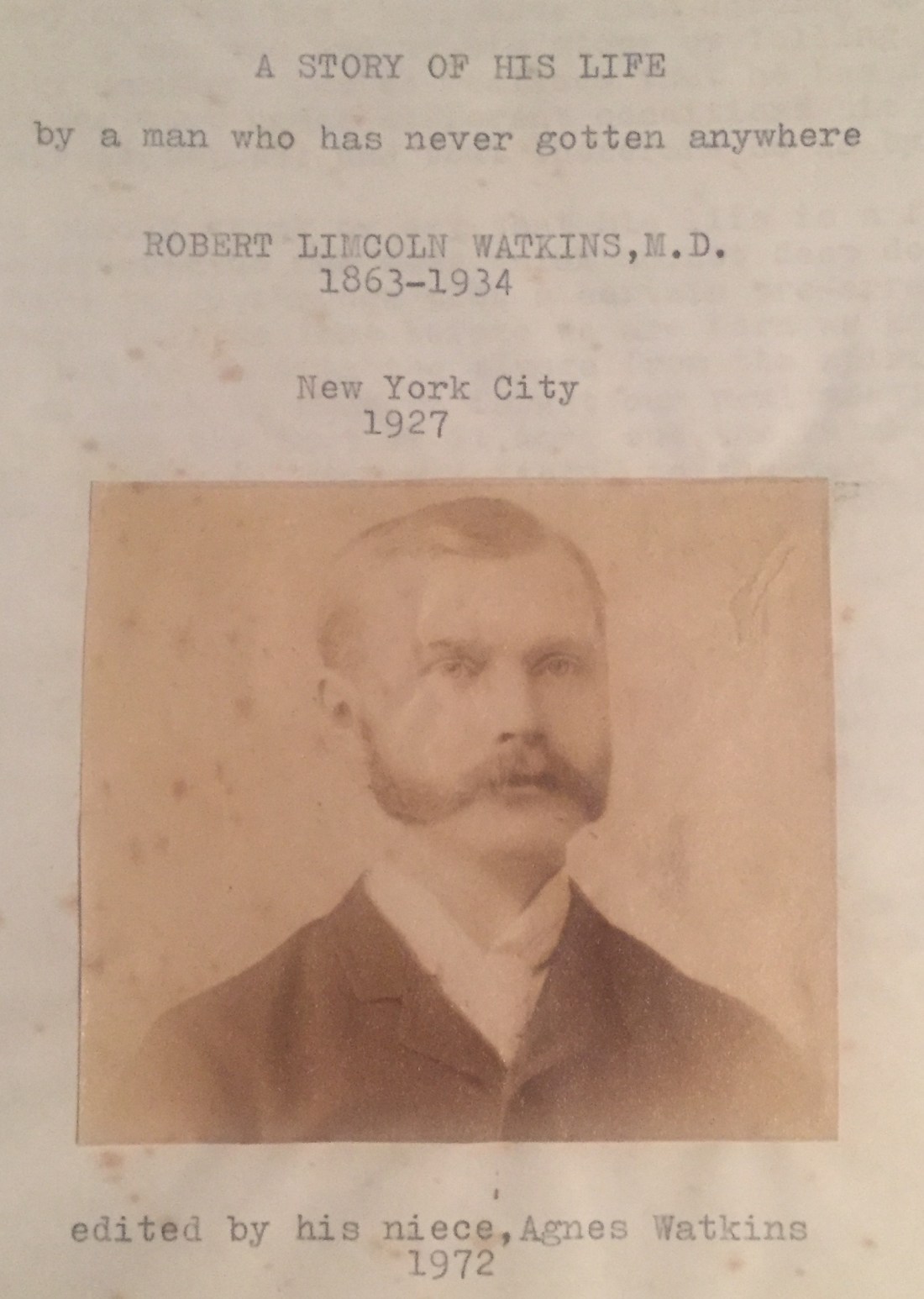

[Background: here’s the preface, forward, and notes from the editor of R.L.W.’s memoir; here’s his account of his upbringing through medical school; here’s when he self-inoculated with tuberculosis and went off to Paris with a charlatan; here’s where he treated typhoid, learned to dance, theorized, and sutured guinea pigs together; here’s where he contracts cholera and hooks his uncle up with testicular juice; here’s his misadventures in self-publishing while treating a slow-motion suicide-by-drinking; here’s where he hangs out with a magician and a vaudevillian; here’s where he recounts his singing career; here’s his ode to a Fulton Market butcher; here’s where he explains his profound love of music; here’s an account of a hard-partying man named Emrich; here are his escapades with a reporter take him to Carnegie’s house; here’s where he gets rooked by a crook of a partner; here’s where he loses his shirt working on an invention for 15 years; and here’s a piece I wrote for New York Press upon first reading the memoir.]

I saw a Marine trying to sleep on a settee with his head sticking out under the arm, and asked him if he wanted to take one of the bunks in my stateroom. He replied that perhaps the man he was with could take the lower bunk, which was wider, and I the upper.

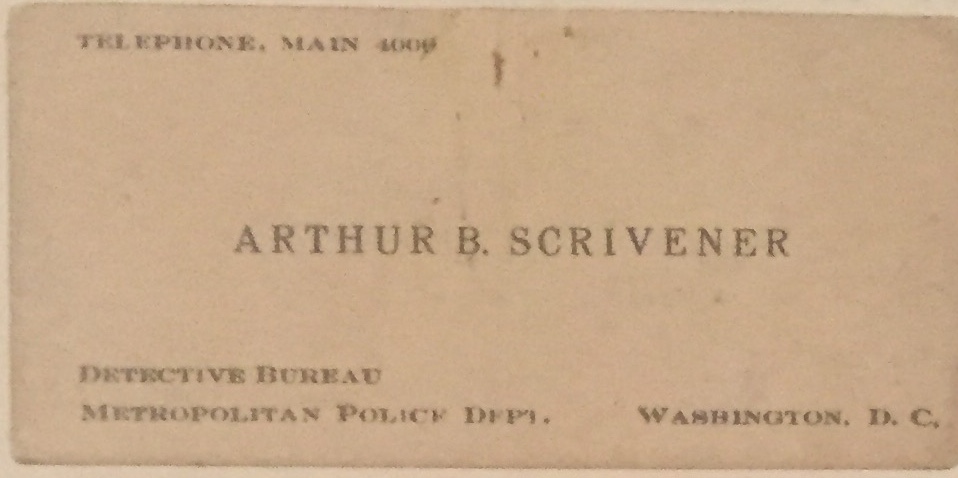

I learned when retiring, and he opened his grip full of guns, that the man the Marine was with was chief of the Washington police Detective Bureau, had taken the Marine with him to Baltimore to round up some deserters, and been unable to get a stateroom.

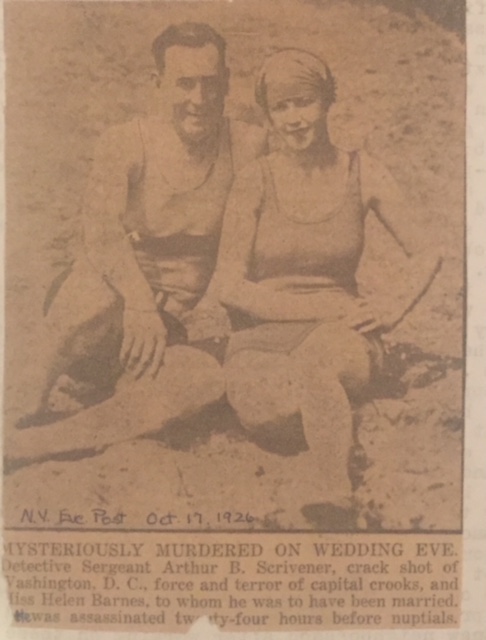

His name was Scrivener. We got breakfast in Washington, and the Marine whispered to me that he hoped the Chief liked him well enough to give him a job, as the pay would be more and he didn’t like his present job. When we parted, the Chief said, “If I can do anything for you, let me know.”

I was unable on that day to do all I had in mind, and at night, being unable to get hotel reservations, I began to think I’d have to sleep on the grass in the park, like many others.

But I happened to think of Scrivener, and called Police Headquarters, who advised me to call the Chief’s house. To my surprise, when I gave my name, although he was not in at the time, the answer was that he had expected to hear from me, and that I was to come to the house.

He came in later, and I shared his room with him, for he was a bachelor and roomed with an Irish family who were musical. While I waited for him to come in, we had Irish songs which I drummed out on the piano.

He left in the middle of the night to go to a neighboring city to arrest some thieves who made it a business to steal automobiles. [He and his soon-to-be-wife were murdered just before their wedding.]

That day, I went to see my cousin, Col. Paul M. Goodrich, in the War College, and found he could get me into the Army. But I was afraid of the examinations, and besides I only wanted the Navy which he had not at first understood was my desire.

I went back to Norfolk, stopping on the way at Old Point Comfort, where by accident I met a young man in the Aviation Corps, Paul Pryable, whose father was a member of the Liederkranz bowling club in New York, as I was. And by the way, this club was loyal to the U.S.A. and had posters all over its rooms saying, “Anyone caught criticizing the Government will be promptly reported to the authorities.” Paul used to fly down close to the windows of his parents hotel when they came down to see him.

One night, when I was back at the Monroe Hotel in Portsmouth, a man in the Navy uniform brought up my suit of clothes that I had left to be pressed at the tailor’s. His room was opposite mine. He was Commodore Phelps.

We became well acquainted, for he was an expert mathematician and I used to try to algebraic problems on him in connection with things I was studying up. He said he took the prize in that subject when at Annapolis. He certainly could do the most difficult ones quickly, and by short-cut methods. He showed me many.

He was on the retired list, but had volunteered for service in the legal department, and went to court every day, taking off his uniform as soon as he got the hotel, for he said he didn’t like to wear it off duty.

I asked him if they ever had any of the guilty ones shot. “Well,” he said, “we have orders from the President to word the judgments so that the President could give pardons.” So I understood his explanation.

By the way, across from the Monroe Hotel a lady lived, 86 years old, who used to keep house for me in New York. She lived with a relative who was an architect in the Navy Yard. It was queer, and I have often thought of it since, she never asked me to a single meal, although I used to see her often.

After staying there to no purpose, I saw an ad in the paper for a reporter on the Baltimore Sun, one who had no experience, it said. So I went to Baltimore, to the Sun office. I noticed a lot of women here, apparently reporters. But word was given to me that, not being familiar with the city, I was not eligible.

Again, one Sunday, I went to Virginia Beach and stayed at a hotel there where the water one night washed up into some of the rooms, although they seemed to think nothing of it. It was an old hotel.

When I went to pay the bill, I found I had no money in my pocket, impulsively exclaiming, “Someone must have stolen it.” I offered to leave my watch. Then I though I might have left it in my clothes in Portsmouth. To my surprise, the proprietor said, “Send it down when you get it. I won’t take your watch.” He knew I was from New York, and it is said in the South that people from there are not to be trusted.

I found my money in Portsmouth, and took it down. It wasn’t far on the electric road. The waitresses at Virginia Beach were young ladies working their way through South Carolina Sectarian College. Talking with one of them, I said that the Navy, or anyway down south here, used different words to the chorus of that popular song, “The Long, Long Trail,” but I couldn’t catch them all. So she wrote them off for me and handed them to me the next morning. Here they are:

There’s a big convoy a-sailing

Into the war zone of France,

Where the submarines are waiting,

But we’ll take a chance;

There’ll be lots of fight and sinkings

Until our ships all come through,

But we will show those U boats

What the U.S. Navy can do.

Well, I went to Wilmington, Del., for I was bound to get into the war game now, and applied to the DuPont Powder Works office. The doctor’s name was Hudson, who was at one time in practice near me in New York, but I did not know him.

“When do you want to go to work?” he said, “Now?”

I said, “Yes.”

“All right, there is a boat for Carney’s Point at one o’clock.”

I had then the greatest sensation of my life, for I was dumped into a camp of 4000 workmen of all nationalities making black powder and nitro-glycerine. The hospital supported 16 doctors, and all slept in one room. I was told to look around and go to work when I felt like it.

It was 8 hours on duty, but we preferred to work 16 rather than loaf around in such narrow quarters. The flu broke out and I was sent by government orders on duty outside the camp, into the town.

I had charge of some gypsies, for the men were compelled to work, something they had never done. Workers were getting big wages, however. The oldest girl in the gypsy camp, 19, would keep saying, “Our mother is dead, and we don’t know what to do.” For the queen, her mother, had dropped dead, and her sister also, both big, handsome, healthy-looking women.

Their bodies were in the morgue and they didn’t look as if they were dead. The young children had the flu, and I ordered fires to be made in the tents. And the youngsters, pretty, curly-haired children, arranged in circles on their rude beds so that this girl might give them menthol and eucalyptus as medicine, and look after them. She fed them lightly and kept them clean. They all recovered, though I did not use the cold air treatment.

All the doctors but two, of whom I was one, had the flu. I slept with a German doctor, and it had been noised about that he had made slurring remarks about the hospital. I was advised to report him, but he was a good doctor and a hard worker, had come there against the wishes of his wife, was along in years. He lived nearby and went home every Sunday. Many thought, “What is he here for?”

So one Saturday I went to Wilmington to follow out the suggestion, but the doctor in charge was in New York. So I took the train for New York. When I arrived, I found he had three addresses, but by luck I selected the right one first. He was located in a high building on 34th St. with his wife, and was surprised to see me because he thought I had been ordered to Virginia.

I told him my story and made him understand that the German doctor was suspect. He quietly removed a telegraph instrument from under a small table, ticked it a while, and said, “Thank you.” I said, “I sleep with the man. What can I do?” He said, “Nothing. There are three secret service men on his track right now.”

I didn’t see anything different in the doctor’s actions when I got back, except that tone day he showed me his photo and quietly remarked, “They made me get a picture last pay day. Did you have to?” All the government did was watch him. He was all right.

Soon I was sent to Penniman, Virginia. Here things were as still as death, a clayey soil, and full of small, tall pine trees, quite different from the noisy, dirty gun powder place. Here I was working for the government only, and TNT was the explosive that was being made.

The doctor, solvency dressed, apparently a young farmer, said, “We are going hunting today. Before you go to work, wouldn’t you like to shoot?” I said, “What do you kill?” He replied, “Birds.” I said, “If I could shoot at some lions or Germans, I might go, but I guess I prefer to work.”

I went on night duty, the second night, for it was a small 35-bed hospital, and an awfully quiet and still place. I said to the nurse, “Do they have any explosions here?” She said, “I’ve been here ever since the war started, and not since I’ve been here.” I said, “I’m going to look up the phone numbers of the staff. I don’t feel comfortable here alone with nothing doing.”

We had no more than got the numbers looked up than the phone rang and a woman said, “Come down to Calibre 4 and bring all the nurses and doctors you can get a hold of.” We had heard a noise like a pistol shot, but thought nothing of it except to remark, “What’s that?”

I called the chief. He was still hunting. Then I called the assistant. He said, “Who phoned?” I said, “A woman.” He said, “Did it sound genuine? Did you hear anything?” I told him I heard something slightly and thought the voice was genuine. He replied, “Take the ambulance and go. We will be down right away.”

A young woman ambulance driver was immediately ready. She drove like mad it seemed to me, over stumps and rocks, at 2 A.M. in the pitch dark night. She said she was from Missouri.

They manufacture TNT in high round tower-like buildings. I looked them over my first day there. We stopped at No. 4 and I ran up the winding stairway, which was left, though much of the side of the building was blown off, to the very top. I saw nothing to do, and as I started back, right behind me was the ambulance driver. Her job was with me, and she was Johnny on the spot.

We found only pieces of clothing and flesh parts. 25 men had been blown to nothing. On the way back we met those who had received the shock, and when we got the to hospital there were many wounded lying around, and many more came in afterwards, stragglers suffering from the shock.

Ten of the staff later came filing in between the lines of wounded that the nurses and orderlies had arranged on the floor. They walked in Indian file, heads down, as if it were a funeral, and they not doctors, but people attending the service, for it was the first explosion at this place. And it was kept out of print.

When Armistice Day came, I was back in Wilmington, and one of the banners in the procession said, “DuPont’s Pills Made the Kaiser Sick.” I stepped into the Y.M.C.A., it was completely deserted. A woman came in with a banner in her hand which she said she had taken from someone in the procession. She was saying, “What shall I do with it? What shall I do with it?” Then I read the banner, which said, “Uncle Sam did it all,” and at the same time noticed she had in her other hand a Union Jack.

“That banner is not right,” she said. “Oh,” I said, taking the banner from her, “it’s near enough right.” She tried to stop me from going out with the banner, but I kept on, though she tried to hinder me as I handed it to someone in the procession. Then I left her, saying as I went, “If you don’t run along, the mob will be after you.”

When I got back to New York, like everybody else, I had to start business all over again. Dr. Benton came to my office to ask if I could do anything for him, for he had been in a camp in the south all through the war. I told him we were all in the same box, having to notify our old patients, in an attempt to resume practice.

Some years after the war, business was most always very slow. I wasn’t at all well, and at times was lonesome in this great city. New York is one of the worst places in which to be alone. I lay on my couch in the office all alone for two or three days. The pain in my chest kept me from getting to the phone.

Finally my nephew [Curtis Watkins, son of brother Edward in Gardner, presumably studying at Columbia] came in and got me something to eat, which made me feel better – well enough to go to my usual haunt in an adjoining city.

But over there I got worse after the first day, and calling Dr. Benton from New York, he said I had pneumonia and was too sick to go back to New York. He had called in several local physicians, and on their promising me that they would not let anyone give me serum, I let them take me to the Presbyterian Hospital in that city.

I was dreaming all right. There was a red book with moving hieroglyphics, Egyptian or Babylonian. There seemed to be ancient horses, and men mounted on them, and occasionally the pages of the book were being turned.

My temperature was 105, but I knew what I was about, for the nurse tried to give me an injection of serum which I fought. The next time she tried it, I said to her, “Do you see that little window up there?” – there was one, high up – “Well, you are going out there if you don’t stop trying that.” I know I attempted, as if she were a man, to seize her by the back of the trousers and shove her out. She afterward told me I gave her a terrible fright.

The next day there filed into the room three men, and the doctors. Dr. Crane said to me, “What do you know about these men?” pointing to my two brothers and my nephew. One had been in before, but the one I referred to was six feet two, a surgeon from Worcester. I said, “How’d you find time to come here?” He said nothing. I went on: “I know two things about him. When he was born he knew that he wanted to be a surgeon. And he knew the girl he wanted for a wife. And I”ll bet he has written her every day he has been away on this trip.”

Arrangements were then made to give me no serums, and my brother and the physician-in-chief agreed to it. I always remember the physician-in-chief’s daily visits. He would listen to my heart with his stethoscope, say nothing, and go off. Till the day he finally said, “All right.”

I have not seen him since, though I called at his house one Sunday long afterwards. The lady who came to the door said, “The doctor sees no one on Sundays,” and shut the door in my face so quick that I had no time to answer.

I made a quick recovery and was out in four weeks. In two months, I was back on the job. They say I was the surprise of the institution. The nurse said I fooled them all.