This episode which I am about to relate should have been put in before my trip to Paris with Dr. Brodnax, for it occurred two to four years earlier.

My uncle, a man about 65, was threatened with what his upstate doctor thought was softening of the brain, and a trip abroad was advised. I was elected to go with him and he became my patient. His mind was weak: he had some property for which he was offered a good price, but one day he would say he would sell, the next he would change his mind, and cry, and spend sleepless nights over it. It broke him all up nervously, and he could not control a naturally calm and beautiful disposition.

We sailed on the New York for Liverpool in August, 1892. It was the maiden trip of the Inman Line, the first American line of transoceanic passenger steamers. It was said on board that when we reached Queenstown we were now an American line. (I shall never forget the peculiarly agreeable impression of the emerald green of Old Erin.) On reaching London by train from Liverpool, we went immediately to a boarding house in Russell Square, previously arranged for.

My patient followed me everywhere, and on the steamer would sometimes crawl into bed with me because he was either homesick or lonesome, although he never complained. Sleeplessness, which was one of his principal troubles, was only relieved by a small dose of whiskey. One night after the theater we were lost in a London fog and had to procure an omnibus to get to our quarters. My uncle was awfully homesick all of the time, and no sooner had we arrived than he wanted to go back. He would read over and over daily the letters from his wife.

[Background: here’s the preface, forward, and notes from the editor of R.L.W.’s memoir; here’s his account of his upbringing through medical school; here’s when he self-inoculated with tuberculosis and went off to Paris with a charlatan; here’s where he treated typhoid, learned to dance, theorized, and sutured guinea pigs together, and here’s a piece I wrote for New York Press upon first reading the memoir.]

The first improvement he had was one day after many days in London, when we took a long walk to the home of some relative of his wife in the largest city in the world. Here, he fell asleep in the rocking chair while we were visiting. He never wanted anyone to know that he was not well, so I quietly told the people to let him sleep. They did. He wrote to his wife the next day that he had just thad the best sleep since he struck that blasted country.

The cholera was raging in Russia and France. I wanted to go. He wanted to go with me, so he suggested to me that we go to se our ambassador Robert Lincoln before we go, to see if it was safe. We had no difficulty in obtaining an audience. He shook hands with my uncle and my uncle said, “I voted for your father, and expect to have a chance to vote for you for President some time.” Then, turning to me, my uncle said, “This is my nephew, Robert Lincoln Watkins, named after you.”

But he advised us to stay away from Paris, as one can never tell what a Frenchman may do, often changing their minds, and they might quarantine us there longer than we wanted to stay.

We went, however, and noticing by the newspaper soon after getting settled that a man by the name of Dr. Hafkin at the Pasteur Institute had discovered a serum for the cure of cholera, had tried it out successfully on rats and guinea pigs, and wanted to try it on human beings, I decided to lend myself for the purpose immediately.

My uncle went along as usual, and there we met another man similarly inclined as my self, a Mr. [Aubrey] Stanhope of the Paris Herald. Dr. H. injected us both, first with the dead cholera germs, and a week later with the live ones. He gave us a chart to keep track of the symptoms that might arise.

After the second injection I was as sick as a horse, and before we could get back to the hotel, I was so faint that, spying the sign of an English doctor, Dr. Chapin, we went in. It seems he was in Paris, too, trying out his theory of checking cholera with ice bags.

After explaining wha had happened, I fell over unconscious on his couch, and when I came to, the old man (he was a big man, about 70, I should judge), was at my feet and remarking “a martyr to science.” My uncle leaned over from behind my head and said, “Well, Robert, I thought you had turned up your toes that time.”

I was soon all right in feeling, but had a high fever that night. Not so bad, though, as to be unable to make a microphotograph of my blood the next morning by the light of the sun with a camera and a new microscope I had purchased in London.

Stanhope went to Hamburg, slept in the beds with the cholera patients, and didn’t get the disease. I worked away by myself in the hospitals of Paris after my own notions. Stanhope was given a big dinner when he got back from Hamburg by the Herald, while Dr. Hafkin and the Pasteur Institute were there to take the honors.

I understand that serum was never accepted as of any special value by the profession in later years. My idea (or one of them) was that I would be able to take some of it back to New York and be the first, if it had panned out, to introduce it. In fact, I did send some of it over to the Academy of Medicine, but was afterward told they never received it. I might remark that the serum left a deposit in one of my finger joints which never disappeared.

I never since have believed in serums, and one reason is that germs are solid, a foreign body, and have got to be worked out of the system. They practically cause a form of rheumatism and often even paralysis, and even with anti-toxin, one of the first that seems to have done much good. In my judgment, and the judgment of many able men I have known, its good effect has been more likely to have been due to a chemical preservative therein, “trikresol,” a carbolic acid derivative. Chemicals are absorbed easily, germs are not, when put into circulation.

Knocking around Paris and the hospitals, I naturally heard of the celebrated Dr. Brown-Sequard. He had gotten up a remedy that had no germs in it, although it was an organic product called Testicular Juice, good for nervous diseases and especially Locomotor Ataxia. The name implies the source of the remedy: he used bulls’ testicles.

I thought it would be good for my uncle. When I called on the doctor, he received me into his private office immediately on my presenting my card, one reason being I suppose that I was an American physician.

He was much interested in what I had done at the Pasteur Institute, sent representatives to my hotel, got the details, and published the same to his Archives of of Anatomy and Physiology (English title), with the photomicrograph. I recollect he said to me, “You will become a better writer as you get older,” for I had written a synopsis and was not used to writing them.

Prof. Brown-Sequard was a slim man of medium height, with a very dark complexion. He spoke perfect English, and was born on the island of Madagascar, a French possession in the Indian Ocean. He married a woman of wealth for his first wife, it is said, and she would not let him practice for fees, but told him to experiment, be an investigator, in which he delighted. It was he would introduced Potassium Bromide for headache and nerve troubles; that first made him celebrated.

I understand his first wife died, and when he married again, he second wife who was also rich told him the same thing, so he really never had to work, but travelled, and became famous by his lectures and his high connections in France.

The day I was there he said Senator Stanford of California was in his waiting room and had come to consult him about Mrs. Stanford. He was quite wrought up because she had been to see Dr. W. Hammond in New York; he had told her that she had an abscess of the liver, and pretended to operate on her in office. The senator said Dr. Hammond had put her under chloroform and introduced a needle, and when she came to had showed her a cup of pus he had drawn; the bill was $2,000. The senator claimed that this pus was not from her system, but that the doctor got it from somewhere else and made her think it was hers.

(Perhaps I should not say this in print.)

I persuaded my uncle to try some of the Testicular Juice for his trouble. The professor said he did not practice, so sent me to a doctor who charged my uncle $20 an injection. He used it till he got the chills, and could not see that it was doing any good. He remarked that he was sick of having that stuff stuck into his backside.

He was sleeping good from the change, for we went to everything in Paris, but he was homesick. So one day before I could stop him he cabled to his wife that he was coming home on the next steamer. He was practically well now, so I did not stop his cable as I had had to do with some previous ones. He made a good recovery and lived many years in good health.

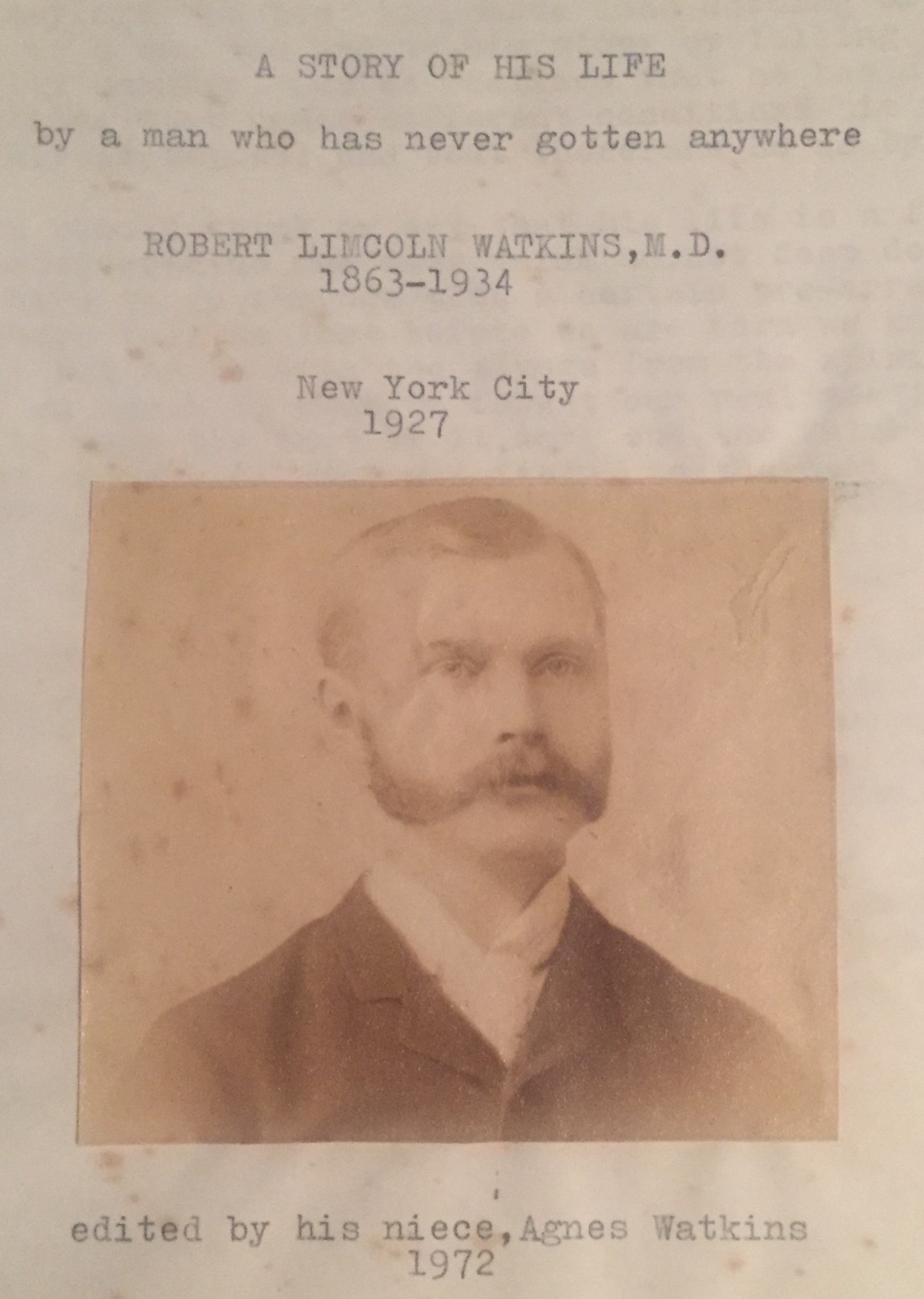

21 thoughts on “A Story of His Life By a Man Who Has Never Gotten Anywhere: Robert Lincoln Watkins, M.D., 1863-1934. A “Martyr for Science” in Paris Procures “Testicular Juice” for His Ailing Uncle.”