By Van Smith

Published in City Paper, Oct. 10, 2007

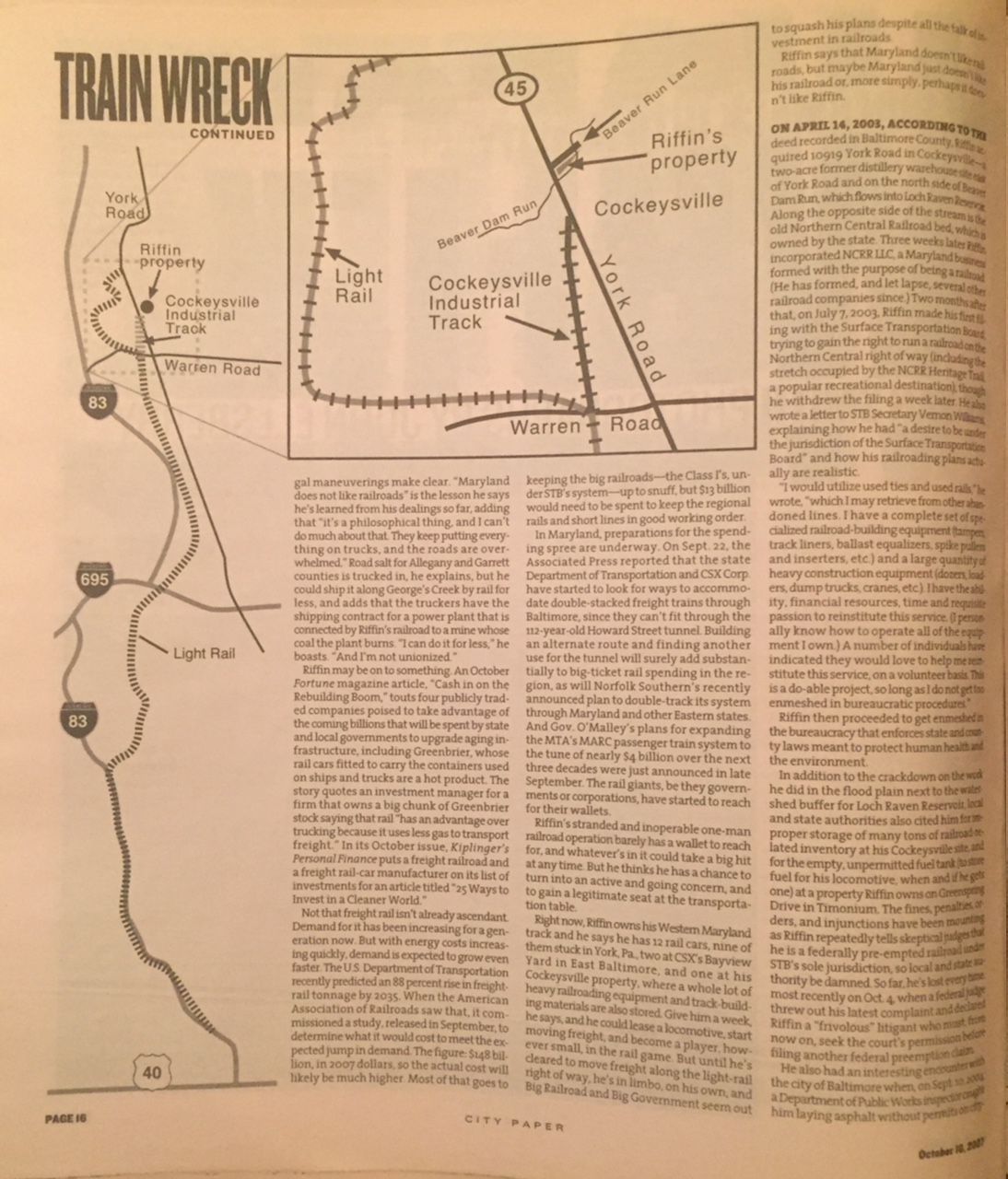

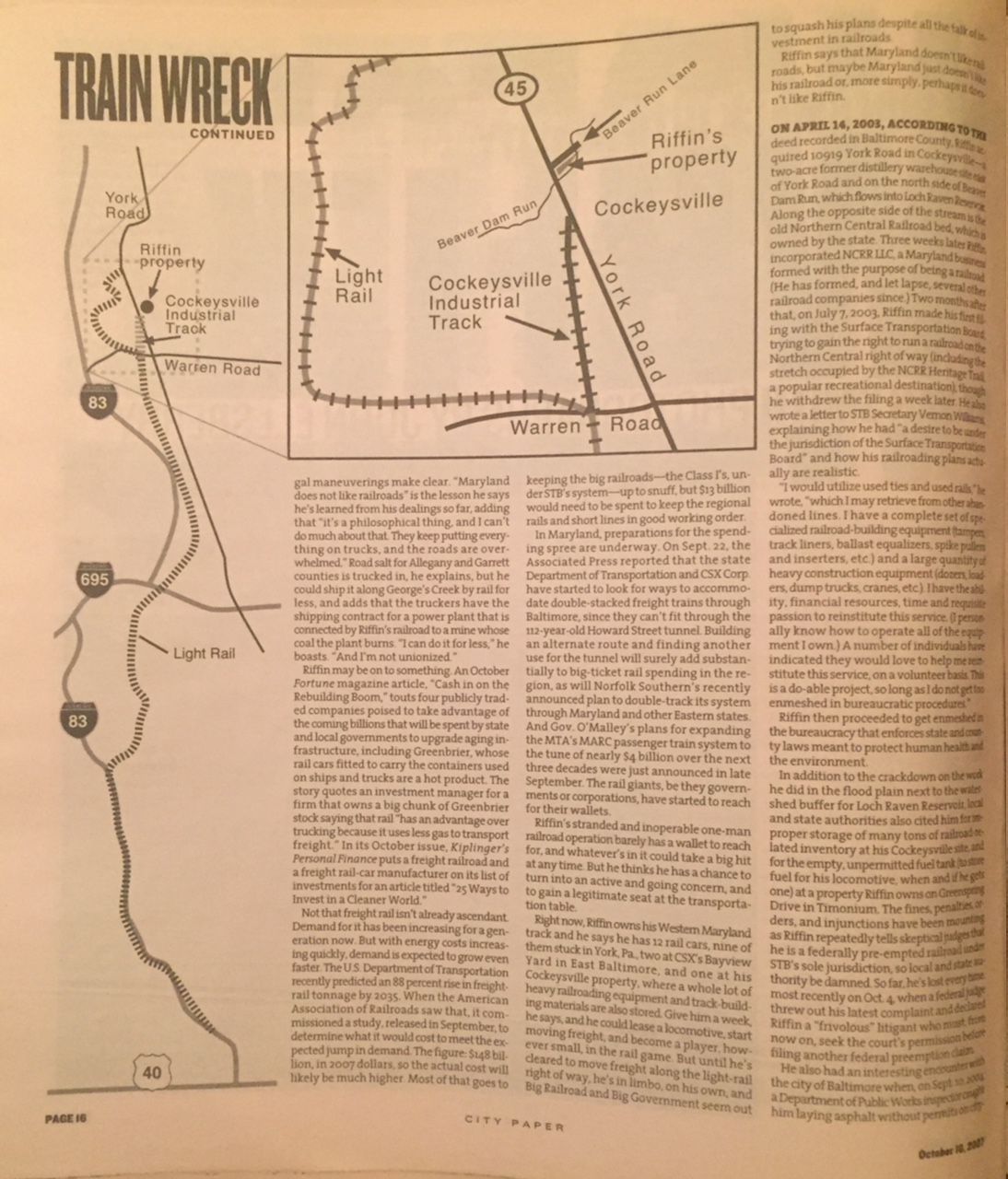

If the law goes his way, a man who calls himself James Riffin says he’ll run freight on railroad tracks between a property he owns in Cockeysville and the nationwide rail network that converges on Baltimore, and at all possible points in between, using a section of light-rail tracks to do it. He’ll do this even though the Maryland Transit Administration (MTA), which has about a billion dollars invested in the light-rail system, and Norfolk Southern, which holds the freight-carrying rights along the line, oppose him. That’s because, if it all goes Riffin’s way, he says that light-rail right of way will be his.

To get to the point where Riffin can make such an outrageous claim, he has boned up on railroad law and used it–with some success, so far–to tangle with transportation giants like the MTA and Norfolk Southern before the federal Surface Transportation Board (STB), which regulates railroads. Since he first began his campaign to start freight-rail service to his Cockeysville property in 2003, James Riffin has become a name a number of state and local officials and several important lawyers know very well, even if they can’t talk about him because he is, was, or could be in litigation with them. MTA spokesman Richard Solli confirms the magnitude of the legal problems Riffin has caused the agency, agreeing that the right of way’s status is “an open question until the board decides.”

If Riffin is going to run freight cars along what used to be the Northern Central Railroad’s right of way in Cockeysville, he faces more than legal challenges. The tracks are largely impassable and, in many areas, nonexistent, so essentially they would have to be completely replaced; pieces of the right of way have been rented out to become parking lots or sold off in real-estate deals. But railroad right of ways, and the laws that regulate them, are long-established and complex things. If the Surface Transportation Board found in Riffin’s favor, it could compel the state and Norfolk Southern to accommodate his claims and his fledgling freight line. The right-of-way property would need to be sorted out and reclaimed. A small railroad bridge would have to be replaced and a new crossing at York Road would have to be installed, disrupting traffic. And if, as Riffin says he wants to do, he interchanges with CSX’s tracks coming out of the Howard Street tunnel in Baltimore, it could theoretically jeopardize the Baltimore Streetcar Museum, which is situated along an old CSX spur. At the very least, Riffin will need to have a large railroad bridge constructed across the Jones Falls. Who’s going to spend all this money? Riffin says he’s willing to bear some reasonable costs, but the MTA damaged the tracks, he argues, so it should repair them.

Lawyers have written in many motions over the past several years that Riffin is abusing the process, that he’s insinuating himself into railroad matters by making unfounded claims to railroad rights, that he’s given to making misleading statements, that he’s a sham. But Riffin doesn’t seem to mind. He just keeps plugging along, preparing for the day when he’ll be driving the locomotive of his own active freight-rail operation, accessing the national rail system via the light-rail tracks that ordinarily ferry passengers between the heart of Baltimore and its northern suburbs. He’s never been entirely sure his dreams would come true, but today it seems more likely than ever before.

Riffin has been behaving as much like a railroad as he can, in the meantime, and that has gotten him into some hot water over his insistence that, like any railroad, he doesn’t have to comply with local and state laws, only federal ones. State authorities didn’t like it, for instance, when in 2004 he started moving large quantities of earth in the Beaver Dam Run flood plain, where his property lies, in order to grade to a higher elevation for the railroad tracks he wants to install. In case the STB and the courts back him, he wants to be ready to start operating.

Riffin continues to pursue this grandiose–some would say impossible–plan because “I have a personal bias against losing railroad right of ways,” he explains. “And I want freight service returned to my property in Cockeysville.”

Meeting with Riffin is difficult to arrange. He’s busy, ever on the move in his worse-for-wear Honda minivan, and often out of cell-phone range. When reached and asked about a convenient time to get together, he says he’s rarely sure what each day will hold, that he has legal research and reading to do, evidence to gather, support from shippers to solicit, and about 8.5 miles of railroad track in Western Maryland that he bought from CSX in August 2006 to tend to, and the best thing is to call him between 8:30 and 9 in the morning on any given day and see whether he has any free time before or after his mid-day meal, which is the only one he eats each day. He’s a one-man operation, and that’s an especially demanding task when the state of Maryland and Baltimore County are both out to shut him down.

Besides, Riffin doesn’t want press. “I’ve actively made attempts to keep this out of the media,” he says, though he doesn’t explain how. When first contacted on Sept. 11 by phone for this article, Riffin immediately asks, “How did you find out about me?” Once it is explained that the discovery was complete happenstance, made while looking for something else entirely in the federal courts, he acquiesces, indicating that, well, if the press is interested, there’s nothing anybody can do about it because it’s all a matter of public record anyway. And he did, as he says, “hit the jackpot” by getting as far as he has unnoticed. But he acknowledges he would prefer it if the matter stays within the tight circle of involved parties: the STB, the MTA, Norfolk Southern, CNJ Rail Corp. of New Jersey (which may want to operate Riffin’s railroad, if it ever gets rolling), and Riffin himself.

His opponents are loath to comment on him, since there is so much active litigation and the likelihood of more. Paul Mayhew, a Baltimore County government attorney who’s been contending for years with Riffin’s federal pre-emption argument, was nice enough to send up the municipal chain of command a list of City Paper‘s questions, but comes back with: “We feel it is best simply to decline comment.” His statement echoes those of other lawyers and spokespeople.

Riffin guesses that his opponents would say this about him, if they felt free to: “Some people would say `eccentric,’ some people would say `kook,’ and some people would say, `Christ, I’d like to see that guy dead.’ If I was in Jersey, I’d be wearing concrete boots at the bottom of some river.”

There are ways short of murder to bring Riffin’s plans to a halt. He could be slapped with liens on his Cockeysville property over outstanding fines and penalties for developing in the flood plain, which he admits he did. He could be forced, at great expense, to move the massive pieces of railroading equipment and machinery from his property, which he’s been ordered to do repeatedly and hasn’t, risking arrest. He could run out of money. But none of that has happened yet.

While Riffin is still very much a Don Quixote with his railroading campaign, his impressive stake in the matter of the light-rail right of way gives him the potential to become David facing Goliath. “It’s about to get real dicey,” he says darkly during one of several hours of phone interviews. When his late-afternoon schedule on Sept. 26 allows for a field trip to point out the route he’d like to use to link with the light rail, Riffin declines to be photographed, saying he doesn’t want to be recognized by Gov. Martin O’Malley. That’s how he sees the magnitude of the forces he’s up against. (Later he agrees to let City Paper publish a photograph in which he walked into the frame while it was being taken, once he’s assured that he’s unrecognizable.)

His black slacks and tucked-in button-down shirt bring the word “professorial” to mind. Work boots suggest an academic area requiring time in the field. His half-glasses are cocked a little on his nose, and his dark hair shows less gray than one would expect for someone in his 60s. He speaks rapidly, imparting with exacting recall his detailed knowledge of railroad case law and the technical aspects of moving freight. Pointing to a section of Cockeysville track overgrown with trees, or where a railroad bridge has been removed, he recites precisely why that’s wrong under STB rules and what it would take to fix it and about how much it would cost. He’s compact, energetic, fast-thinking, and, as if in front of a classroom, he’ll call on you: “Remember what I told you about whether you become a common carrier if you buy a line of railroad?” The man’s in full command of the subject matter, and many others besides, and he likes to test attentive students to make sure they’re still following.

Towson University confirms that James Riffin was an assistant professor of business administration in what is now the College of Business and Economics from August 1978 to June 1981. There were other teaching gigs, too, Riffin recalls, while he was studying graduate law and industrial relations at University of Pennsylvania, continuing an academic career that began during the Vietnam War at the University of California, Berkeley. Later, he made some money developing the Timonium Road property now owned by the Maryland Athletic Club, and he describes crafting money-saving deals to reduce corporate lighting costs. Only after he acquired the Cockeysville tract in 2003, he says, did he start to look closely at the possibilities of railroads.

“Until I came along,” Riffin observes smugly, “no one paid any attention. And then I said, `I’d like some freight-rail service in Cockeysville.'”

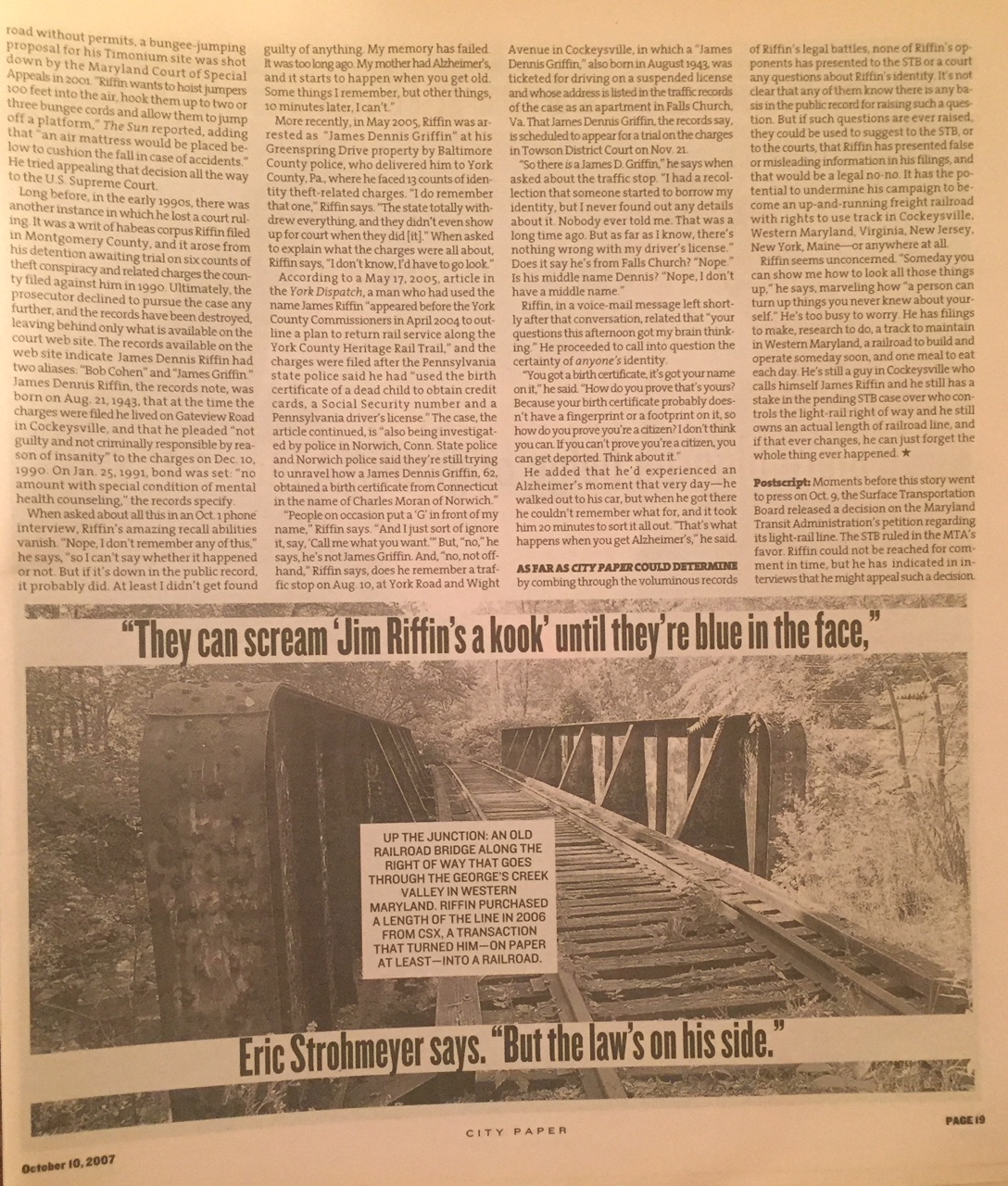

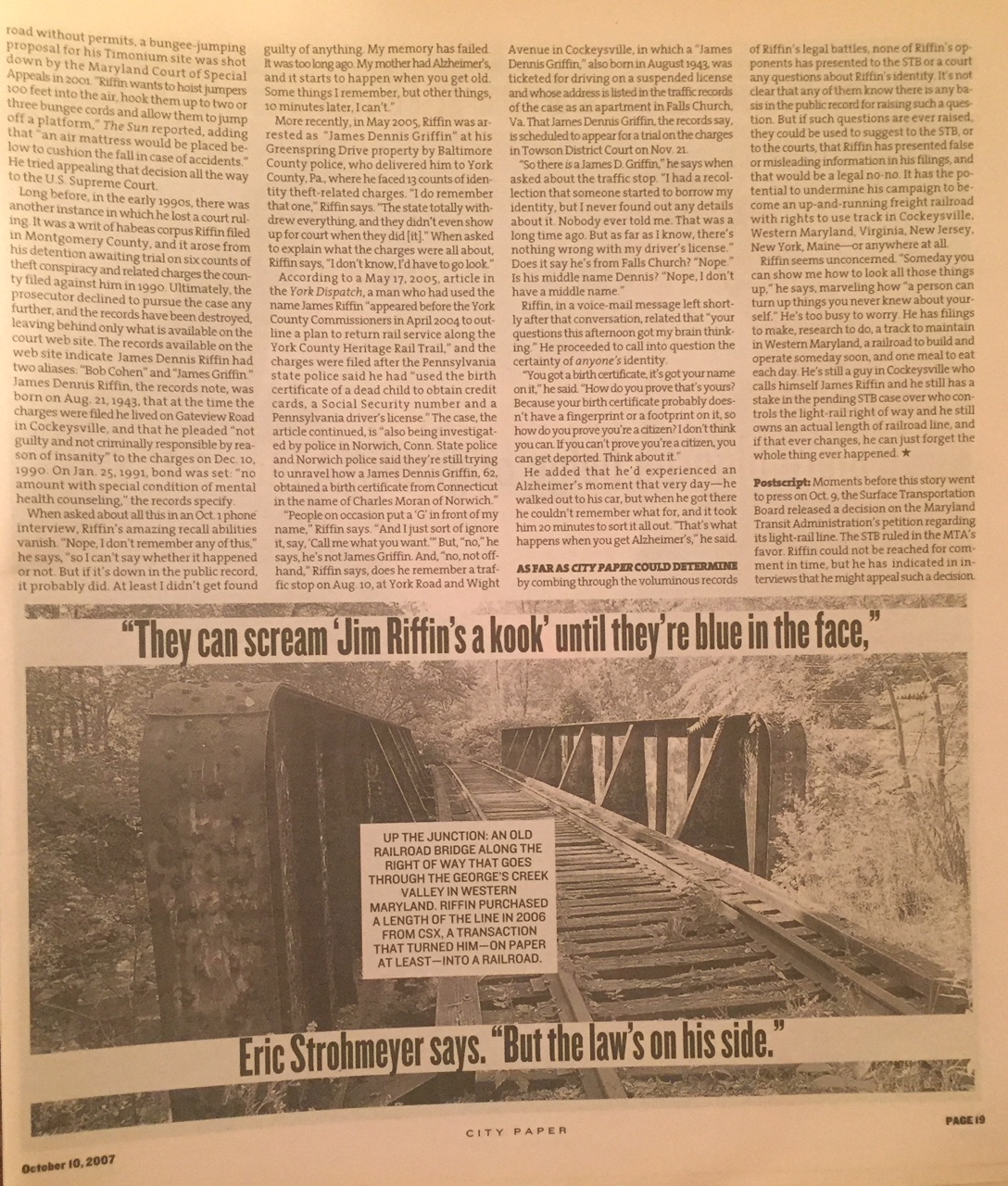

Then, in a sense, Riffin became a railroad. A little over a year ago, he bought some track in Allegany County along George’s Creek south of Frostburg on down to Westernport, about 8.5 miles in all, on a right of way anywhere from 30 to 100 feet wide–44 acres of dirt, rocks, and rail. The George’s Creek Subdivision, it’s called in the STB records; after CSX sold it to Riffin, the STB classified him as a Class III railroad, commonly known as a short line.

“Someone suggested I buy it,” Riffin explains about the track purchase. “And I did, pretty much sight unseen. And then I went about finding out what it was I bought. It has the potential to have a lot of freight traffic, but there’s also a lot of politics.”

Riffin has run into a lot of that in his short railroading career, as the records of his legal maneuverings make clear. “Maryland does not like railroads” is the lesson he says he’s learned from his dealings so far, adding that “it’s a philosophical thing, and I can’t do much about that. They keep putting everything on trucks, and the roads are overwhelmed.” Road salt for Allegany and Garrett counties is trucked in, he explains, but he could ship it along George’s Creek by rail for less, and adds that the truckers have the shipping contract for a power plant that is connected by Riffin’s railroad to a mine whose coal the plant burns. “I can do it for less,” he boasts. “And I’m not unionized.”

Riffin may be on to something. An October Fortune magazine article, “Cash in on the Rebuilding Boom,” touts four publicly traded companies poised to take advantage of the coming billions that will be spent by state and local governments to upgrade aging infrastructure, including Greenbrier, whose rail cars fitted to carry the containers used on ships and trucks are a hot product. The story quotes an investment manager for a firm that owns a big chunk of Greenbrier stock saying that rail “has an advantage over trucking because it uses less gas to transport freight.” In its October issue, Kiplinger’s Personal Finance puts a freight railroad and a freight rail-car manufacturer on its list of investments for an article titled “25 Ways to Invest in a Cleaner World.”

Not that freight rail isn’t already ascendant. Demand for it has been increasing for a generation now. But with energy costs increasing quickly, demand is expected to grow even faster. The U.S. Department of Transportation recently predicted an 88 percent rise in freight-rail tonnage by 2035. When the American Association of Railroads saw that, it commissioned a study, released in September, to determine what it would cost to meet the expected jump in demand. The figure: $148 billion, in 2007 dollars, so the actual cost will likely be much higher. Most of that goes to keeping the big railroads–the Class I’s, under STB’s system–up to snuff, but $13 billion would need to be spent to keep the regional rails and short lines in good working order.

In Maryland, preparations for the spending spree are underway. On Sept. 22, the Associated Press reported that the state Department of Transportation and CSX Corp. have started to look for ways to accommodate double-stacked freight trains through Baltimore, since they can’t fit through the 112-year-old Howard Street tunnel. Building an alternate route and finding another use for the tunnel will surely add substantially to big-ticket rail spending in the region, as will Norfolk Southern’s recently announced plan to double-track its system through Maryland and other Eastern states. And Gov. O’Malley’s plans for expanding the MTA’s MARC passenger train system to the tune of nearly $4 billion over the next three decades were just announced in late September. The rail giants, be they governments or corporations, have started to reach for their wallets.

Riffin’s stranded and inoperable one-man railroad operation barely has a wallet to reach for, and whatever’s in it could take a big hit at any time. But he thinks he has a chance to turn into an active and going concern, and to gain a legitimate seat at the transportation table.

Right now, Riffin owns his Western Maryland track and he says he has 12 rail cars, nine of them stuck in York, Pa., two at CSX’s Bayview Yard in East Baltimore, and one at his Cockeysville property, where a whole lot of heavy railroading equipment and track-building materials are also stored. Give him a week, he says, and he could lease a locomotive, start moving freight, and become a player, however small, in the rail game. But until he’s cleared to move freight along the light-rail right of way, he’s in limbo, on his own, and Big Railroad and Big Government seem out to squash his plans despite all the talk of investment in railroads.

Riffin says that Maryland doesn’t like railroads, but maybe Maryland just doesn’t like his railroad or, more simply, perhaps it doesn’t like Riffin.

On April 14, 2003, according to the deed recorded in Baltimore County, Riffin acquired 10919 York Road in Cockeysville–a two-acre former distillery warehouse site east of York Road and on the north side of Beaver Dam Run, which flows into Loch Raven Reservoir. Along the opposite side of the stream is the old Northern Central Railroad bed, which is owned by the state. Three weeks later Riffin incorporated NCRR LLC, a Maryland business formed with the purpose of being a railroad. (He has formed, and let lapse, several other railroad companies since.) Two months after that, on July 7, 2003, Riffin made his first filing with the Surface Transportation Board, trying to gain the right to run a railroad on the Northern Central right of way (including the stretch occupied by the NCRR Heritage Trail, a popular recreational destination), though he withdrew the filing a week later. He also wrote a letter to STB Secretary Vernon Williams, explaining how he had “a desire to be under the jurisdiction of the Surface Transportation Board” and how his railroading plans actually are realistic.

“I would utilize used ties and used rails,” he wrote, “which I may retrieve from other abandoned lines. I have a complete set of specialized railroad-building equipment (tampers, track liners, ballast equalizers, spike pullers and inserters, etc.) and a large quantity of heavy construction equipment (dozers, loaders, dump trucks, cranes, etc.). I have the ability, financial resources, time and requisite passion to reinstitute this service. (I personally know how to operate all of the equipment I own.) A number of individuals have indicated they would love to help me reinstitute this service, on a volunteer basis. This is a do-able project, so long as I do not get too enmeshed in bureaucratic procedures.”

Riffin then proceeded to get enmeshed in the bureaucracy that enforces state and county laws meant to protect human health and the environment.

In addition to the crackdown on the work he did in the flood plain next to the watershed buffer for Loch Raven Reservoir, local and state authorities also cited him for improper storage of many tons of railroad-related inventory at his Cockeysville site, and for the empty, unpermitted fuel tank (to store fuel for his locomotive, when and if he gets one) at a property Riffin owns on Greenspring Drive in Timonium. The fines, penalties, orders, and injunctions have been mounting as Riffin repeatedly tells skeptical judges that he is a federally pre-empted railroad under STB’s sole jurisdiction, so local and state authority be damned. So far, he’s lost every time, most recently on Oct. 4, when a federal judge threw out his latest complaint and declared Riffin a “frivolous” litigant who must, from now on, seek the court’s permission before filing another federal preemption claim.

He also had an interesting encounter with the city of Baltimore when, on Sept. 10, 2004, a Department of Public Works inspector caught him laying asphalt without permits on city-owned watershed property behind his Cockeysville warehouse. Riffin told the city he’d done the work “inadvertently” and promised to restore the site to its prior condition. On the same day, Riffin pulled out a sheet of Northern Central Railroad letterhead and typed out a letter to DPW director George Winfield, informing him that he’d like to “construct a railroad right-of-way across a portion of Baltimore City’s watershed property.” It took almost three weeks for Winfield to send out a letter denying the proposal.

Baltimore County Councilman T. Bryan McIntire recalls that, a few years ago, Riffin approached him about plans to turn the distillery warehouse into a railroad-themed restaurant with a dinner train leaving from a second-floor railroad queue. That was part of his hope to link with York, Pa., along the old Northern Central right of way and, while he was at it, he said he wanted to arrange to move Blue Mount Quarry’s stone by rail south to Cockeysville–something he still talks about. The idea caught some attention, including an October 2004 Baltimore Smart CEO article that concluded, “It doesn’t look like Riffin’s dream of being a railroad tycoon has much chance to succeed.”

Riffin ran into obstacles at every turn, but he kept making more proposals and filing more notices with the STB. Sometimes they’d be denied, sometimes he’d withdraw them, but in going through the paces, he kept open his lines of communication with the board as he learned its ways.

On Dec. 22, 2006, the MTA asked the STB to rule that federal approval wasn’t needed for the MTA’s 1990 purchase of 14.2 miles of right of way from Conrail to build the light rail north of North Avenue in Baltimore. In the same filing, the MTA also asked the board to confirm that freight rights and obligations that would have placed the MTA under the board’s authority were not transferred to MTA when the 1990 sale took place. Ordinarily, such a deal would entail that the purchaser maintain the right of way for “common carriers”–that is, the MTA would have had to keep all the track intact and ready for use in the event that Norfolk Southern wanted to use the line.

The reason the MTA was asking for clarification about the matter in 2006, 17 years after it bought the right of way, is that in 2005 Norfolk Southern applied to officially “abandon” the section of its track used by the light-rail line. A railroad officially abandoning a track involves attesting that it no longer uses it, and would therefore like the STB to relieve the railroad of its track maintenance responsibilities, which is a requirement of railroad law. The MTA had been maintaining the track, and Norfolk Southern had been running freight on it between midnight and 5 a.m., when the light rail doesn’t run. When the MTA shut down that light rail line to install a second track in 2004, Norfolk Southern stopped running freight on it and soon started abandonment proceedings to completely dissolve its responsibility for the line.

In response, Riffin filed an offer with the STB to take over Norfolk Southern’s freight-carrying rights. This bought him some time to dig into the board’s records and uncover the MTA’s failure to clarify with the board that it had no need to worry about maintaining the tracks for “common carriers” in 1990.

Riffin pointed this out to the STB, and Norfolk Southern’s request for abandonment was denied in 2006 because, thanks to Riffin, the right of way’s ownership had been called into question and needed to be properly established. When the MTA filed its petition to clear it all up, Riffin protested, and the federal board will issue a ruling on the matter when it is good and ready. The validity of the 1990 right-of-way transaction and all that hinges on it appear to be hanging in the balance, as is the question of whether the MTA has an obligation to maintain the entire right of way–not just the parts it uses–for freight traffic.

“Because of the uncertainty created by the issues raised related to MTA’s acquisition, use and ownership of this line,” wrote Charles Spitulnik, the MTA’s outside counsel on the case, in an Aug. 21 letter to the STB, “MTA is prevented from using and improving this asset for its intended passenger transit purposes and from making changes that will further enhance the safety of operations on this line.”

When asked about this letter, Spitulnik apologetically says he is “not authorized to talk to you because the matter is in litigation.” MTA spokesman Richard Solli agrees that the board’s answers to the MTA’s questions about the 1990 right-of-way purchase should have been sought 17 years ago, rather than today, but “everybody back then thought that everything they were doing was being done properly, and until we’re told differently, we think the actions we’ve taken since 1990 were appropriate. We’re just asking [the STB] to move things along so all the parties can go ahead and do the things that all the parties need to do. As for how the STB decides, we’ll cross that bridge when we get to it.”

If the board rules that the MTA’s 1990 purchase did not fall under STB authority, and that the MTA was not responsible under federal law for maintaining the line for freight use, then Riffin’s enterprise will remain trapped piecemeal on the unconnected properties he owns. But if the board rules that the MTA’s purchase did fall under its authority, then the fact that the MTA appears to have dismantled and sold off portions of a disused section of the right of way known as the Cockeysville Industrial Track, Riffin argues, could make the MTA responsible for repairing that damage, to the tune of millions of dollars. Riffin has letters from shippers along the right of way supporting the prospect of renewed freight service, including Packard Fence Co., SealMaster Paving Products, and Buschemi Stone Masonry. If the Cockeysville Industrial Track reopens, then Riffin’s property, which is across York Road from it, will be that much closer to getting rail access.

If the current light-rail right of way ends up back in Norfolk Southern’s hands, then Norfolk Southern will likely apply again to abandon freight service on the line, giving Riffin another chance to offer to provide the freight service instead. If Riffin’s offer is accepted by the federal board, then the MTA would have to negotiate light-rail rights with Riffin, who says his first order of business would be restoring freight service to Cockeysville.

After Riffin purchased the George’s Creek line and found the MTA’s weak spot with the light rail right-of-way issue, things kicked into high gear. He sought STB approval to obtain short-line rights on old railroad beds in Virginia, New Jersey, New York, and Maine. On Jan. 12, the world learned for the first time that he intended to operate a railroad on 2.2 miles of the old abandoned Maryland and Pennsylvania (aka Ma & Pa) right of way that runs through city-owned property along Falls Road that is currently occupied by the Baltimore Streetcar Museum and a newly-constructed bike trail. CSX, the MTA, the museum, and the city of Baltimore opposed Riffin with strongly worded pleadings. The museum’s interpretation of Riffin’s proposal was that it would supplant the museum’s operations and shut down the bike trail.

Museum board member Christopher McNally, who is also serving as its counsel in this as-yet-undecided matter, in his filing told the federal board that Riffin’s railroad plan “would likely obliterate [the museum]’s entire operation in the Jones Falls Valley.” McNally declines to be quoted for this article, except to say this of Riffin: “We will fight him to the legal bitter end in terms of any effort to build a railroad in the Jones Falls Valley.”

Riffin’s STB filings often jangle the nerves of opposing parties, but in the Ma & Pa case, he says he has no actual use for the ripped-up and paved-over line, and no intention of disrupting the Baltimore Streetcar Museum operation or the bike trail whatsoever. All he wants, he says–and he says this is “on hold until I figure out what’s going to happen with the Cockeysville line”–is to build a $20 million railroad bridge over Falls Road from the light-rail right of way to the CSX tracks, and to do so, he has to cross the Ma & Pa right of way. Hence the STB filing that caused McNally and everyone else involved such grief.

But, Riffin adds, McNally’s filing was helpful. In the event that Riffin wants access to the line in the future, he says he needs to show it was used to move freight after its official 1958 abandonment. McNally’s STB filings state that the Baltimore Streetcar Museum was the last to get rail service on the line when it “received railroad ties delivered on flatcars in the 1970s.”

Riffin was tickled with that. But he filed something recently in an STB case involving light-rail plans in Norfolk, Va., that tickled him even more because of the response it prompted from Norfolk Southern. Riffin says the company’s lawyer on the case, James Paschall, wrote an “unflattering biography” of Riffin in a Sept. 6 filing that sought to sanction him and bar him from appearing in any future STB matters involving Norfolk Southern.

“It was a personal attack, really,” Riffin says. “I wanted to push his sensitive button, and I did, and I guess I hit it pretty hard.” The lawyerless novice gets one over on Big Railroad’s experienced counsel here and there, and Riffin delights in it, and in the reaction. “Sometimes I have fun playing with people’s minds,” he says.

Paschall wrote in his 42-page filing: “In an astonishing, but perhaps not surprising, display of misinterpretation, misrepresentation and illogic, Riffin has filed a frivolous Comment and sham Notice” in the city of Norfolk’s light-rail matter, and thereby “again abuses the Board’s processes and harasses parties who appear before the Board for legitimate purposes.” Paschall proceeded to recite Riffin’s entire history of participating in STB matters, casting it all in the worst light possible.

On Oct. 1, Riffin filed his reply to Paschall. The conclusion of the 18-page document read, in part: “For the foregoing reasons, Riffin would ask that the Board deny NS’ Motion for Sanctions, and Riffin would further ask that the Board admonish Mr. Paschall for his unprofessional behavior in this proceeding. . . . Perhaps next time, Mr. Paschall will consider walking down the smooth path, rather than the thorny path.”

Riffin’s enemies have said many negative things about his railroading aspirations, but he has at least one friend: Eric Strohmeyer, vice president and chief operating officer of CNJ Rail Corp. of New Jersey. Strohmeyer calls Riffin “a very nice guy, and an extremely smart guy. He’s arguing the case extremely well. It’s an amazing transformation from having an interest in railroads to being a full-fledged railroader.”

“Our interest,” Strohmeyer continues, “is we have rail properties up in New Jersey, and we control some New Jersey track, and we got involved with James Riffin when Norfolk Southern had tried to abandon the Baltimore light-rail line to Cockeysville. Our firm would be an independent, third party to operate the line, should it be returned to freight service under Riffin.

“We estimate we could move 3,600 car-loads of freight per year over the [Cockeysville Industrial Track], and that would take 12,000 truckloads per year off the Baltimore Beltway,” Strohmeyer adds. “Right now, there are ethanol trucks rolling through Baltimore streets. If we moved 150 to 200 rail cars of ethanol per year instead, that would be 600 to 800 fewer truckloads, and it would take an explosive substance off the public streets. And remember, railroads pay for their own track maintenance, but trucks rely on publicly maintained roadways.”

Strohmeyer begins to talk about how Riffin’s case fits in with the larger transportation-planning picture. He points out that “as cities grow, we can’t build brand-new railroads for freight, we’ve got to share these corridors. The MTA does not believe they have to co-exist with freight, but there needs to be smart transportation planning, and excluding freight is shortsighted transportation policy.

“What Riffin’s started is a major battle, and right now it’s just Riffin and the state,” he says. “But if the STB’s decision runs afoul of the law, all hell will break loose because the MTA has unlawfully ended freight service on the Cockeysville line even though shippers along the line want service, and the MTA knows it. This is going to go to the courts unless everybody agrees to agree. The MTA is playing Russian roulette with the taxpayers of the state of Maryland.

“They can scream `Jim Riffin’s a kook’ until they’re blue in the face,” Strohmeyer concludes. “But the law’s on his side.”

The law hasn’t always been on Riffin’s side. Even before he started to build his railroad without permits, a bungee-jumping proposal for his Timonium site was shot down by the Maryland Court of Special Appeals in 2001. “Riffin wants to hoist jumpers 100 feet into the air, hook them up to two or three bungee cords and allow them to jump off a platform,” The Sun reported, adding that “an air mattress would be placed below to cushion the fall in case of accidents.” He tried appealing that decision all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Long before, in the early 1990s, there was another instance in which he lost a court ruling. It was a writ of habeas corpus Riffin filed in Montgomery County, and it arose from his detention awaiting trial on six counts of theft conspiracy and related charges the county filed against him in 1990. Ultimately, the prosecutor declined to pursue the case any further, and the records have been destroyed, leaving behind only what is available on the court web site. The records available on the web site indicate James Dennis Riffin had two aliases: “Bob Cohen” and “James Griffin.” James Dennis Riffin, the records note, was born on Aug. 21, 1943, that at the time the charges were filed he lived on Gateview Road in Cockeysville, and that he pleaded “not guilty and not criminally responsible by reason of insanity” to the charges on Dec. 10, 1990. On Jan. 25, 1991, bond was set: “no amount with special condition of mental health counseling,” the records specify.

When asked about all this in an Oct. 1 phone interview, Riffin’s amazing recall abilities vanish. “Nope, I don’t remember any of this,” he says, “so I can’t say whether it happened or not. But if it’s down in the public record, it probably did. At least I didn’t get found guilty of anything. My memory has failed. It was too long ago. My mother had Alzheimer’s, and it starts to happen when you get old. Some things I remember, but other things, 10 minutes later, I can’t.”

More recently, in May 2005, Riffin was arrested as “James Dennis Griffin” at his Greenspring Drive property by Baltimore County police, who delivered him to York County, Pa., where he faced 13 counts of identity theft-related charges. “I do remember that one,” Riffin says. “The state totally withdrew everything, and they didn’t even show up for court when they did [it].” When asked to explain what the charges were all about, Riffin says, “I don’t know, I’d have to go look.”

According to a May 17, 2005, article in the York Dispatch, a man who had used the name James Riffin “appeared before the York County Commissioners in April 2004 to outline a plan to return rail service along the York County Heritage Rail Trail,” and the charges were filed after the Pennsylvania state police said he had “used the birth certificate of a dead child to obtain credit cards, a Social Security number and a Pennsylvania driver’s license.” The case, the article continued, is “also being investigated by police in Norwich, Conn. State police and Norwich police said they’re still trying to unravel how a James Dennis Griffin, 62, obtained a birth certificate from Connecticut in the name of Charles Moran of Norwich.”

“People on occasion put a `G’ in front of my name,” Riffin says. “And I just sort of ignore it, say, `Call me what you want.'” But, “no,” he says, he’s not James Griffin. And, “no, not offhand,” Riffin says, does he remember a traffic stop on Aug. 10, at York Road and Wight Avenue in Cockeysville, in which a “James Dennis Griffin,” also born in August 1943, was ticketed for driving on a suspended license and whose address is listed in the traffic records of the case as an apartment in Falls Church, Va. That James Dennis Griffin, the records say, is scheduled to appear for a trial on the charges in Towson District Court on Nov. 21.

“So there is a James D. Griffin,” he says when asked about the traffic stop. “I had a recollection that someone started to borrow my identity, but I never found out any details about it. Nobody ever told me. That was a long time ago. But as far as I know, there’s nothing wrong with my driver’s license.” Does it say he’s from Falls Church? “Nope.” Is his middle name Dennis? “Nope, I don’t have a middle name.”

Riffin, in a voice-mail message left shortly after that conversation, related that “your questions this afternoon got my brain thinking.” He proceeded to call into question the certainty of anyone’s identity.

“You got a birth certificate, it’s got your name on it,” he said. “How do you prove that’s yours? Because your birth certificate probably doesn’t have a fingerprint or a footprint on it, so how do you prove you’re a citizen? I don’t think you can. If you can’t prove you’re a citizen, you can get deported. Think about it.”

He added that he’d experienced an Alzheimer’s moment that very day–he walked out to his car, but when he got there he couldn’t remember what for, and it took him 20 minutes to sort it all out. “That’s what happens when you get Alzheimer’s,” he said.

As far as City Paper could determine by combing through the voluminous records of Riffin’s legal battles, none of Riffin’s opponents has presented to the STB or a court any questions about Riffin’s identity. It’s not clear that any of them know there is any basis in the public record for raising such a question. But if such questions are ever raised, they could be used to suggest to the STB, or to the courts, that Riffin has presented false or misleading information in his filings, and that would be a legal no-no. It has the potential to undermine his campaign to become an up-and-running freight railroad with rights to use track in Cockeysville, Western Maryland, Virginia, New Jersey, New York, Maine–or anywhere at all.

Riffin seems unconcerned. “Someday you can show me how to look all those things up,” he says, marveling how “a person can turn up things you never knew about yourself.” He’s too busy to worry. He has filings to make, research to do, a track to maintain in Western Maryland, a railroad to build and operate someday soon, and one meal to eat each day. He’s still a guy in Cockeysville who calls himself James Riffin and he still has a stake in the pending STB case over who controls the light-rail right of way and he still owns an actual length of railroad line, and if that ever changes, he can just forget the whole thing ever happened.

Postscript: Moments before this story went to press on Oct. 9, the Surface Transportation Board released a decision on the Maryland Transit Administration’s petition regarding its light-rail line. The STB ruled in the MTA’s favor. Riffin could not be reached for comment in time, but he has indicated in interviews that he might appeal such a decision.