Physicians are liable to run into all kinds of complex situations.

I had not been in practice many years, and was located in Harlem, which was just then building up, when a rather dilapidatedly dressed man of about 50 came into my office one morning, complaining of a cough and spitting blood. I concluded it was a temporary and not serious condition, and gave him the advice for such a case.

I told him it would take some little time, and asked him to come in again in a few days. He replied that he did not live in town, and could I tell him where he could get a room, since he was going to continue under my care and did not want to run back and forth, and he would settle with me afterward. I told him that the only place I could think of was my washwoman, Mrs. Shrebers, who had some empty rooms and took roomers, so I remembered her saying.

One morning, some ten days after, the washwoman came in, evidently in trouble, and said, “Mr. Mooney came and took a room with me, but he has gone away, and I haven’t seen him in several days. You recommended him, so I though he was all right, but he took my boarder’s overcoat.”

I said I didn’t know him, he just dropped in like any patient – but he had given me his address in Philadelphia. So, to help the old lady out, I telegraphed to the police in Philadelphia, and they replied that there was no such address, and they knew no one by that name.

When she came back for the answer, as above, she said, “I didn’t tell you all before – you sent him and I thought he was all right. He said he had a store in Philadelphia, and did well, so we went to a minister on the East Side and got married.”

He had told the druggist’s clerk that he kept a saloon in Philadelphia, had hit a man on the head with a bottle in a fight, and was afraid to go back. So the poor old lady doesn’t know who or where her husband is, nor does she know her real name to this day.

[Background: here’s the preface, forward, and notes from the editor of R.L.W.’s memoir; here’s his account of his upbringing through medical school; here’s when he self-inoculated with tuberculosis and went off to Paris with a charlatan; here’s where he treated typhoid, learned to dance, theorized, and sutured guinea pigs together; here’s where he contracts cholera and hooks his uncle up with testicular juice; here’s his misadventures in self-publishing while treating a slow-motion suicide-by-drinking; here’s where he hangs out with a magician and a vaudevillian; here’s where he recounts his singing career; here’s his ode to a Fulton Market butcher; here’s where he explains his profound love of music; here’s an account of a hard-partying man named Emrich; here are his escapades with a reporter take him to Carnegie’s house; here’s where he gets rooked by a crook of a partner; here’s where he loses his shirt working on an invention for 15 years; here’s where he travels south during the World War and becomes a DuPont physician who’s present for a mass industrial accident; and here’s a piece I wrote for New York Press upon first reading the memoir.]

I used to have a patient from a neighboring city, a fine-looking lady of about 50, who required treatments over some months. I became so well acquainted with the family that one summer we all took a trip together on the boat to Richmond, Virginia.

The daughter was along, a girl of about 18 years old. Nothing momentous or out of the way happened, but in those, my younger, days, this was quite a responsibility in certain ways. And I did not enjoy the trip any too well.

Perhaps a year or two after our return, the daughter was more or less ailing, and I was called over to her home. I had reason to suspect an attempt at foul play somewhere, so I consulted the Pinkerton detective agency, through the Parkhurst Society, a society for the prevention of vice for I was resolved to prepare myself for the next visit.

I sent a woman detective to the house as a boarder, for it was a private house, and she did a good job. She did not compromise me, although I protected myself with another to watch her in certain movements as things went on.

But the lady of the house was ready with her scheme one day, and sent for me to go over to see the daughter who was sick in bed. I went upstairs to the room, where I found the daughter in bed, and her mother. My detective, it seems, was in the closet.

The girl said she had much pain in the back, and a sore throat. As I began my examination, the mother left the room. And no sooner had I finished examining the young lady (fine-looking, dark complexioned, like her mother) than I said, “Jennie, do you want to quit this life and be decent?”

She looked at me in surprise and began to cry. I continued, “There is a woman outside who will look after you, and I’ll see that you get out of the house” – for I was not sure she was of age and could leave on her own. “You know what kind of a woman your mother is.”

The crying became louder, and the mother came into the room. She sat on the bed asking the daughter, as I stood by her side, what the matter was. The daughter did not answer.

So I did. I said, “I was telling your daughter what kind of a woman you were.” For my detective had been out with her, and found she was still at the old game as before her marriage, associating with other men and collecting money from them. She had a special pull on a bank cashier whose mistress she was before she married her present husband.

I have since learned that the husband did not care, and probably was in the game, too.

The mother fell over on the bed and began a fusilade at me. I said to the daughter again, “Do you want to leave, or stay with your mother?” She preferred to stay, so failing in my foolish attempt at reformation, I got out.

The detective said had many lawyers at the house the next day, but the detective gave herself away, and I never heard any more about the case.

Some twenty-five years later, calling at the house of the people who had introduced me, they asked what ever became of that young girl. I said the last time I saw her she was on the Boardwalk at Atlantic City, and looked as if she were soliciting.

They were astonished, so I told them the whole story – to their further surprise. For these people were quite religious. I have heard recently that they are all dead except the girl, who was sickly, and living with an unmarried man at a certain hotel.

She fell into her mother’s ways, all right. Such is the world, but I did not know it then.

Once, long after this, the girl had the nerve to write me for a loan of $3000, and I think also called at my office once on a similar errand.

A young lady, 23, of Stamford, Conn., was taken with melancholia. The family were old patients of mine, and after she had been in that condition for two weeks, they sent for me to come up.

I found her very bad. She would neither eat nor talk, and threatened to jump out the window. It was brought on by her imagining that she had been insulted by a young man when she was out at a dance, though she had been all the time with her brother. She was getting worse, so I suggested that instead of getting an expensive nerve specialist, the get a man I knew who was in the truss business.

His name was Bunker. He was tall and big, with black hair and eyes. He was no doctor, though he was often called “Doctor” by those who knew him, for he had studied various diseases he ran across, or that his friends had; headworker some at osteopathy and massage; and even in his young days had docked horses’ tails when it was against the law.

He was an American, born in Maine, and claimed to have Indian blood. He was more or less clairvoyant, and familiar with hypnotism. He could almost always be found in a game of cards – claimed he saw through the cards.

The people where he lived said he claimed all sorts of wonders, and that he not infrequently got full of whisky, when he would pat his stomach with his hand and call it, “papoose, papoose.”

One time I saw him take care of a redheaded boy named Charlie who was the bully of the other boys around 14th St. and Seventh Ave. They were playing cards and getting mad, and Charlie called him a cheat and an Indian papoose. He took Charlie by the seat of his pants, held him right out the window of the four-story building, and told him to take that back or he would drop him. Charlie was never mean around there any more.

I told my patients all these things, and we decided to try him if I could locate him, for it was ten years or more since I had seen him. After phoning a while, I got in touch with this genius, and he said he would come up to see the girl for $50 or less.

He walked into the room where the girl was, her hair all over her face and down her back. He walked right up to her. She wouldn’t speak to him. He told the nurse to take her upstairs, take her clothes off, and put her to bed.

We all followed but the father, who went downstairs to fix the furnace fire. Old Bunker put his hand under the clothes and began to work the stomach muscles, talking to her softly, just as a minister would. “Now you may think you have done something wrong, but you haven’t,” etc.

Soon, in fifteen minutes or so, she looked at him. And he said, “Now, Mary, I’ve done all I can for you. God will have to do the rest.”

Immediately she sat up in bed and called, “Daddy!” It was the first time she had spoken in two weeks.

I ran downstairs and told her father his daughter was calling for him. (Her mother was dead.) When he came in the room, she said, “Daddy, pray for me.” The old man hadn’t prayed for years, I do believe, but he got down on his knees and did so then.

She began to eat and get well from that moment. Though she did have a slight relapse, it did not last.

Bunker wanted to go back to see the girl again, but I knew he had her under his power, and I did not want him on familiar terms with the family. For he was an unprincipled man, evil at times, when he chose. He had two wives, and was married to a policeman’s widow, though this was not generally known.

Such cases I knew had to be worked with quickly, for they so often turn in to a permanent mania.

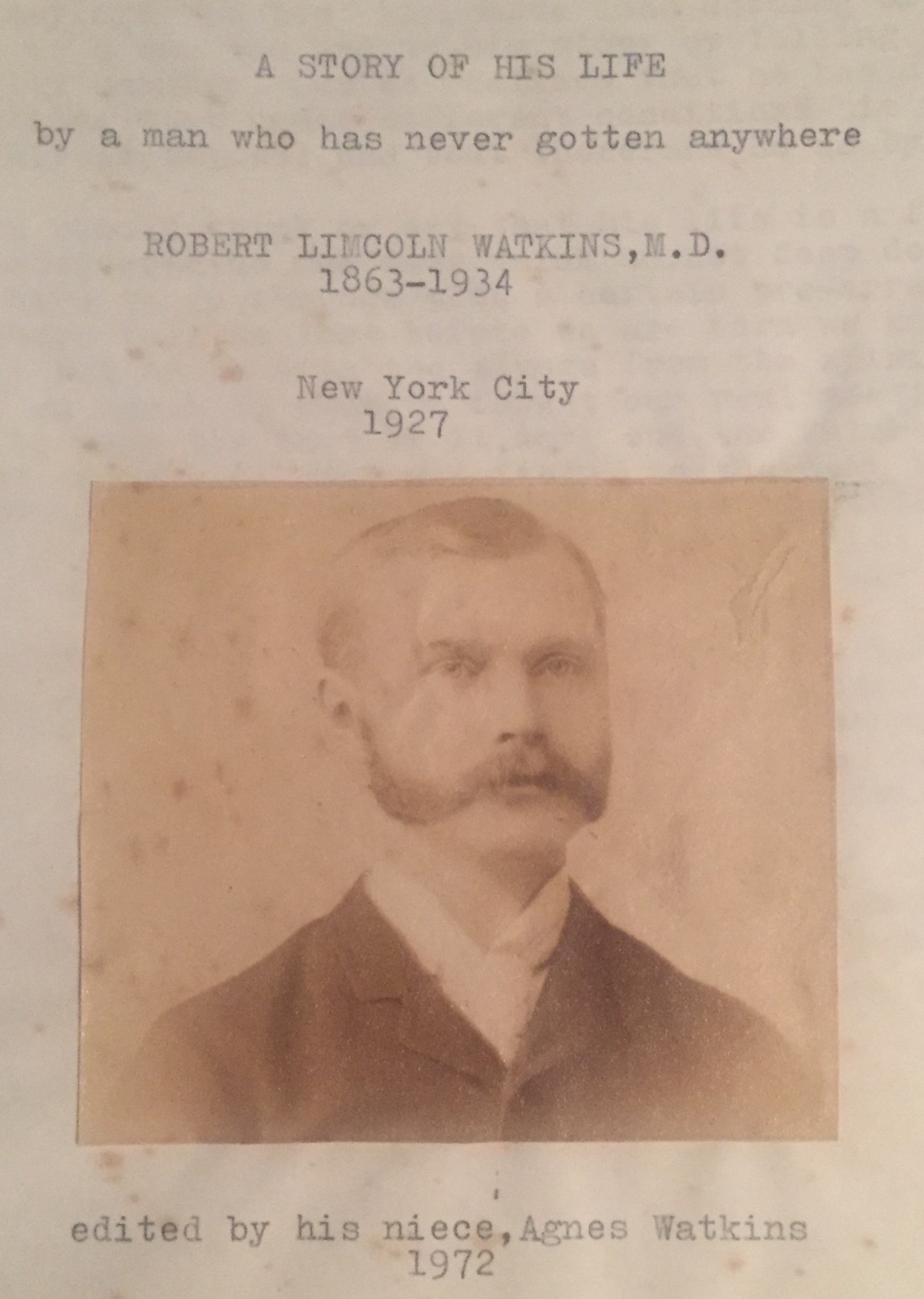

9 thoughts on “A Story of His Life By a Man Who Has Never Gotten Anywhere: Robert Lincoln Watkins, M.D., 1863-1934. The Doc Treats a Philadelphia Scoundrel and a High-Falutin’ Hooker, and Gets Bunker from Maine to Treat a Girl’s Melancholia.”